| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://wjon.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 16, Number 6, December 2025, pages 645-660

MiR-301a-3p Promotes Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Progression via PTEN Suppression in Tumor Cells and the Microenvironment

Hai Yun Lina, c, Guang Yan Lia, c, Wen Long Lianga, Yao Wanga, Bai Yang Fua, Qi Guang Dua, Yu Tong Zhanga, Zhong Kai Xua, He Cuia, Xi Chena, Zheng Fub, d, Jian Guo Zhanga, d

aDepartment of Breast Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, Heilongjiang 150001, China

bNanjing Drum Tower Hospital Center of Molecular Diagnostic and Therapy, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Jiangsu Engineering Research Center for MicroRNA Biology and Biotechnology, NJU Advanced Institute of Life Sciences (NAILS), Institute of Artificial Intelligence Biomedicine, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210023, China

cThese authors contributed equally to this study.

dCorresponding Authors: Jian Guo Zhang, Department of Breast Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, Heilongjiang 150001, China Email:; Zheng Fu, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital Center of Molecular Diagnostic and Therapy, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Jiangsu Engineering Research Center for MicroRNA Biology and Biotechnology, NJU Advanced Institute of Life Sciences (NAILS), Institute of Artificial Intelligence Biomedicine, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210023, China

Manuscript submitted September 9, 2025, accepted October 14, 2025, published online October 31, 2025

Short title: MiR-301a-3p Promotes TNBC Progression

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon2670

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), the most aggressive breast cancer subtype, poses a severe threat to women’s health. Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) critically influence tumor progression within the tumor microenvironment (TME), but the role of the miR-301a-3p/PTEN axis in TNBC requires elucidation.

Methods: PTEN expression and effects were assessed by comparing clinical TNBC tissues with adjacent normal tissues. Mechanisms were investigated using integrated dataset analysis, luciferase reporter assays, functional cell experiments (assessing malignant phenotypes), co-culture models with ADSCs, and in vivo tumor models. Molecular expression (PTEN, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA)) and pathway activity (phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT) were evaluated.

Results: MiR-301a-3p was upregulated in TNBC and directly bound PTEN’s 3'-UTR to suppress its expression. Functionally, miR-301a-3p enhanced tumor cell malignancy. Tumor cell-derived exosomes transported miR-301a-3p to ADSCs in the TME, suppressing PTEN, activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, and upregulating VEGFA secretion. In vivo, modulating miR-301a-3p levels significantly altered tumor growth, PTEN expression, and VEGFA production in tumor and peritumoral tissues.

Conclusion: MiR-301a-3p drives TNBC progression via exosome-mediated crosstalk with ADSCs, forming a PTEN/PI3K/AKT/VEGFA signaling axis. It represents a promising therapeutic target and novel biomarker with significant clinical value for TNBC treatment.

Keywords: Triple-negative breast cancer; PTEN; miRNA; ADSCs; VEGFA; Microenvironment

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Breast cancer remains one of the most common and challenging malignancies worldwide [1, 2]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), characterized as a distinct molecular subtype of breast cancer, accounts for roughly 12% of all cases [3, 4]. TNBC lacks three key molecular markers of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2), progesterone receptor (PR), and estrogen receptor (ER) [5]. TNBC is characterized as earlier age of onset, greater aggressiveness, rapid disease progression, higher risk of early metastasis, and elevated recurrence rates. This malignancy results in significantly increased mortality within the first 3 years after diagnosis. Even when receiving identical treatment conditions, the prognosis of TNBC remains worse than that of other breast cancer subtypes. Additionally, TNBC displays high molecular heterogeneity that molecular features and biomarkers may vary across different patients even within the same subtype. This complexity undoubtedly complicates research into TNBC [6-9]. Hence, TNBC represents a critical challenge and cutting-edge research area in breast cancer studies due to its unique molecular characteristics and therapeutic limitations.

Key modalities in contemporary breast cancer therapy include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and immunotherapy. However, therapeutic outcome towards TNBC is barely satisfactory, primarily because this subtype lacks expression of three key receptors that commonly serve as therapeutic targets in other breast cancer types. Additionally, TNBC patients exhibit heterogeneous responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)/ programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors). These factors led to the poorest prognosis among TNBC patients relative to other breast cancer subtypes. In recent years, advances in molecular biology technologies have spurred increasing research on aberrantly expressed genes, miRNAs, and signaling pathways in TNBC. These discoveries provide new directions for molecular targeted therapies against TNBC [10]. In-depth investigations into TNBC’s molecular mechanisms, identification of novel biomarkers, and development of precise targeted treatment regimens are essential for improving patient survival rates and clinical outcomes.

Defined as the local ecosystem encompassing tumor cells, the tumor microenvironment (TME) includes mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) as pivotal components that functionally contribute to tumor advancement. Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), located within adipose tissue, constitute a specialized subset of MSCs [11]. ADSCs exert their functions through secretion of abundant cytokines. For instance, they release interleukin-1α (IL-1α) [12], IL-6 [13], and IL-10 [14] to mediate anti-inflammatory effects. Additionally, ADSCs could secrete transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), placental growth factor (PGF), and angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) by activating pathways such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT, Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and RhoA/Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) to promote endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis [15, 16]. Increasing evidence highlights the pivotal role of the TME in cancer progression. The stromal components, including ADSCs, could interact with tumor cells to foster growth, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [17-19]. However, the molecular mediators of this interaction remain unclear. Functioning as a key tumor suppressor, PTEN modulates cellular growth, survival, and apoptotic pathways. Dysregulation of PTEN is implicated in breast cancer progression, where inactivation correlates with heightened aggressivity and adverse clinical outcomes [20, 21]. Hence, understanding the mechanism of PTEN loss in TNBC is essential for elucidating the pathology of TNBC’s aggressive phenotype, and thus contributing to the development of targeted therapies.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), which are ∼20-nucleotide non-coding single-stranded RNAs, are abundant in bodily fluids (e.g., blood, urine) and highly enriched in exosomes [22]. The mechanism by which miRNAs regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally involves binding the 3'-UTR of target mRNAs. This binding event leads to either translational suppression or mRNA decay, culminating in gene silencing, rather than direct involvement in protein synthesis [23-25]. Furthermore, miRNAs can influence tumor progression by modulating tumorigenesis, angiogenesis around tumors, and tumor drug resistance.

MiR-301a has recently emerged as a research hotspot in oncology, with aberrant expression documented in gastric [26], pancreatic [27], prostate [28], and cervical cancers [29]. In breast cancer, miR-301a also demonstrates dysregulated expression. Studies indicated that elevated miR-301a levels were correlated with poor prognosis in TNBC [30]. However, research on its underlying molecular mechanisms remains limited. Actually, miR-301a exists as two distinct isoforms of miR-301a-3p and miR-301a-5p. However, current studies often fail to differentiate between them, which represents a significant oversight in miR-301a research. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no in vivo studies in mouse models have been conducted to date and existing research is confined to in vitro cell experiments. This limitation provides an incomplete understanding of the relationship between miR-301a and tumor growth.

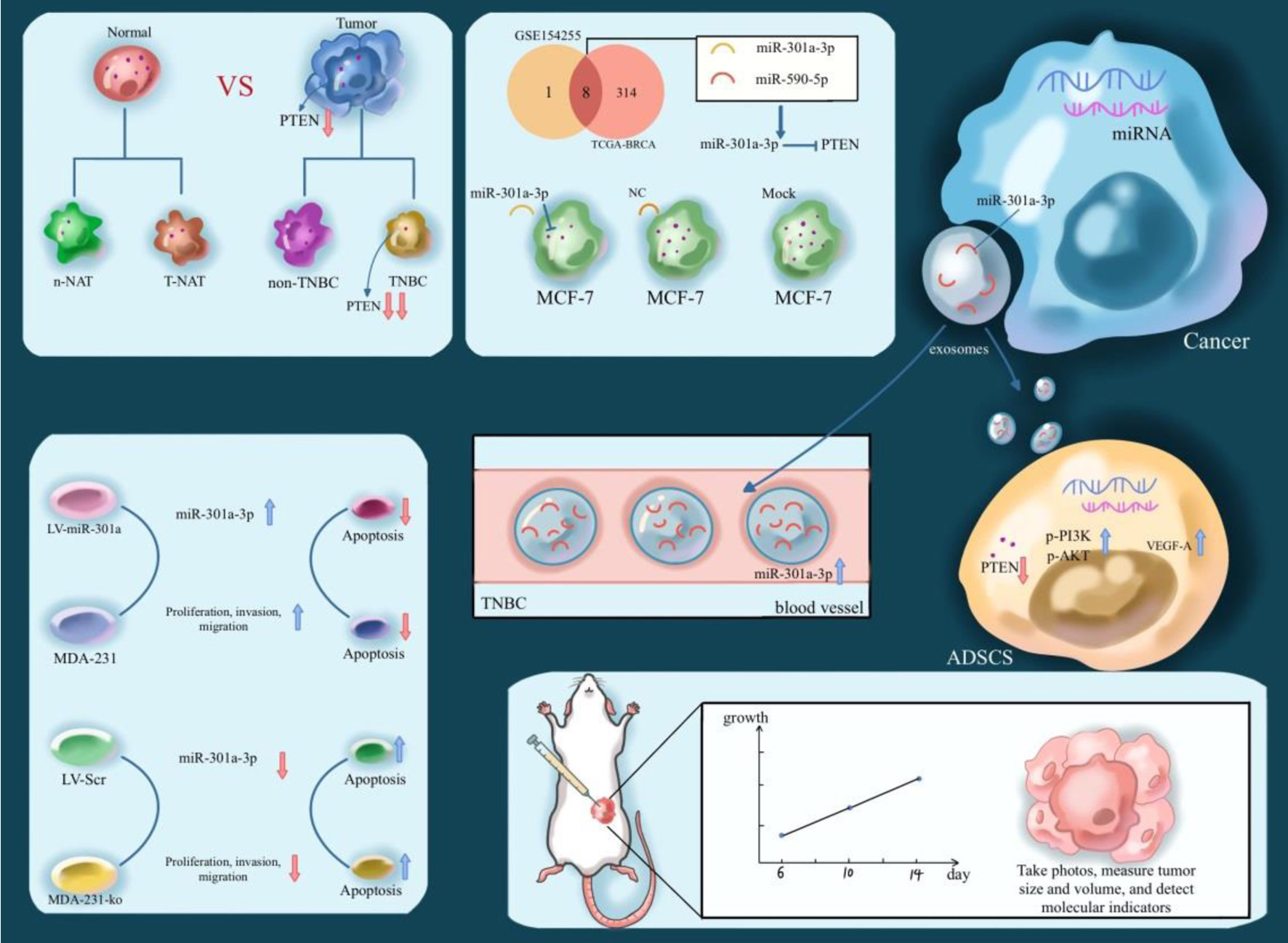

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the role of miR-301a-3p in TNBC by characterizing its impact on PTEN expression and downstream signaling pathways in the TME, with the goal of identifying potential therapeutic targets. To achieve this, we first compared PTEN levels in clinical TNBC tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues. Integrated dataset analyses and luciferase reporter assays confirmed that miR-301a-3p directly binds to the 3'-UTR of PTEN, suppressing its expression. Functional studies, including cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) proliferation assays, transwell migration assays, wound healing assays, and apoptosis assays, demonstrated that miR-301a-3p significantly enhances tumor cell proliferation and migration while inhibiting apoptosis. Furthermore, by isolating exosomes from patient serum and culture supernatants of various cell lines, we identified the highest miR-301a-3p levels in TNBC-derived exosomes. These exosomes were shown to modulate the PTEN-PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, ultimately upregulating VEGFA expression. To validate these findings in vivo, we performed intratumoral injections of adenovirus overexpressing miR-301a-3p or miR-301a-3p knockout constructs in mouse models, bidirectionally confirming that miR-301a-3p promotes breast cancer growth. Complementary analyses using Western blotting, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), and immunohistochemistry (IHC) further established that activation of the PTEN-PI3K/AKT pathway increases VEGFA expression and secretion (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Illustration of the expression level and biological effects of PTEN in TNBC. TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer. |

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Major laboratory supplies

Centrifuge tubes, cell culture flasks, and 0.2-mL PCR tubes were sourced from BIOFIL. Pipettes of various models were obtained from Gilson Pipettes. Pipette tips were bought from Axygen. The 70-mL polycarbonate ultracentrifuge bottles were supplied by Beckman Coulter.

Tissue samples

Surgical specimens of breast cancer were collected from patients at The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. Written informed consent was acquired from all participants prior to surgery. The study protocol and all procedures involving human tissues were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. Post-resection, tissue specimens were rapidly frozen using liquid nitrogen and archived at -80 °C. All experimental protocols were executed in compliance with both international ethical principles (Declaration of Helsinki) and institutional guidelines established by The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University.

Cell lines and culture

All cellular models were obtained from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology and Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cell line identity was authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling. Cell cultures were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher) + 12% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified chamber. Cell lines were maintained for fewer than 20 passages and routinely tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

Transfection

Transient transfection of small RNA oligonucleotides and plasmids was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, USA). For miRNA overexpression, miRNA mimics (RiboBio, China) were employed.

Bioinformatic analysis of public databases

PTEN expression in breast cancer was analyzed using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort, encompassing 1,097 tumor tissues and 114 normal controls. Subtype-specific analysis evaluated PTEN levels in Luminal (n = 566), HER2-positive (n = 37), and TNBC (n = 116) subtypes. TNBC-associated miRNA expression profiles were interrogated through integrated analysis of TCGA and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, GSE154255) datasets. This identified nine significantly upregulated miRNAs in GSE154255 and 322 upregulated miRNAs in TCGA. Potential PTEN-targeting miRNAs were predicted using RNAhybrid [31] with default parameters [32]. Further building upon these analyses, overall survival (OS) was evaluated in the TCGA BC cohort stratified by miR-301a expression levels (low: n = 495; high: n = 767). To control for treatment-related confounders, a subgroup analysis was conducted specifically in treatment-naive patients (low miR-301a: n = 91, high miR-301a: n = 108) who received no prior systemic therapy.

Protein extraction and Western blotting

Protein extraction utilized RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime) supplemented with: 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Beyotime) for protease inhibition and 1X phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Beyotime). We measured protein concentrations using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit, separated equal protein loads via 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; Bio-Rad, USA), and electroblotted them onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-Buffered Saline Tween (TBST) for 60 min, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-PTEN (ab267787, 1:1,000, Abcam), anti-AKT (ab314110, 1:1,000, Abcam), anti-phospho-AKT (p-AKT; ab38449, 1:1,000, Abcam), anti-PI3K (ab191606, 1:1,000, Abcam), anti-phospho-PI3K (p-PI3K; ab278545, 1:1,000, Abcam), and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, 60004-1-Ig, 1:1,000, Proteintech). GAPDH served as the loading control. Membranes received three 10-min TBST washes prior to 60-min incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:4,000; room temperature). Protein signals were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent and quantified using a chemiluminescence imaging system.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

We extracted total RNA using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher, USA). RNA concentration and purity were determined spectrophotometrically, and integrity was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. We performed reverse transcription with: 1) Applied Biosystems’ TaqMan™ MicroRNA RT Kit (stem-loop primers) for miRNA [33]; 2) Takara’s PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (oligo(dT)18 primers) for protein-coding genes. We quantified miRNAs via TaqMan™-based qRT-PCR employing: 1) UNG-free Universal PCR Master Mix II; 2) Target-specific TaqMan™ MicroRNA Assay probes. We assessed protein-coding gene expression via SYBR™ Green-based qRT-PCR with custom primers and SYBR™ Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA). qRT-PCR (ABI 7300 system) used: 1) Thermal profile: 95 °C/10 min → 40 × (95 °C/15 s → 60 °C/60 s); 2) SYBR Green dissociation: 95 °C/15 s → 60 °C/60 s → 95 °C/15 s; 3) Data analysis: 2(−ΔΔCt) method with U6 (miRNA) and GAPDH (mRNA) normalization. All assays were performed in technical triplicates.

Luciferase reporter assay

The dual-luciferase reporter plasmids were commercially sourced from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ-operations in China). To test miRNA binding sites, pMIR-REPORT luciferase reporter vectors were constructed containing the putative miR-590 or miR-301a binding sites within the PTEN 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR). Corresponding mutant plasmids harboring site-directed mutations were generated to assess binding specificity: the original miR-590 binding site sequence (ATAAGTT) was mutated to TATTCAA, while the original miR-301a binding site (TTGCACT) was mutated to AACGTGA. Luciferase activity was quantified employing the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Vazyme Biotech, China), in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Briefly, cells were co-transfected with the reporter constructs, miRNA mimics or controls. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were lysed, and relative luminescence was quantified. Renilla luciferase activity served as the reference for normalization of Firefly luciferase activity in each sample.

Cell proliferation assay

We measured the proliferation rates of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells using the CCK-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Japan). Briefly, we seeded cells in 12-well plates and transfected them with small RNA oligonucleotides. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, we harvested the cells and re-seeded them into 96-well plates. At 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 h after re-seeding, we added 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent to each well and incubated the plates at 37 °C for 120 min. The microplate reader was used to detect absorbance at 450 nm post-incubation.

Cell migration assay

Transfected MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were trypsinized at 24 h post-transfection, resuspended in serum-free RPMI-1640, and seeded into 8-µm pore Millicell inserts (Millipore, USA) within 24-well plates. Lower chambers contained 20% FBS medium. After 24 h incubation, non-migrated cells were removed by swabbing. Post-migration processing included: 4% PFA fixation (20 min), 0.5% crystal violet histochemical staining (15 min), and blinded quantification in five randomly chosen microscopic fields per transwell insert.

Apoptosis assay

After treatment, cell pellets were obtained via centrifugation (4 °C, 5 min), subjected to cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) washes, and incubated with Annexin V-FITC staining solution (BD Biosciences Kit I, USA) following the standardized protocol. Immediate analysis (< 60 min) was conducted on an Attune NxT flow cytometer.

IHC analysis

We processed 5-µm paraffin sections of breast tumors and adjacent adipose tissue by: 1) deparaffinizing in xylene; 2) rehydrating through graded ethanols; 3) blocking endogenous peroxidase with 3% H2O2. Sections were blocked with 5% BSA (60 min, RT), then incubated with primary antibodies (4 °C, overnight). After PBS washes, we applied: 1) biotinylated anti-IgG secondary antibody (Beyotime, 60 min); 2) avidin-biotin complex (ABC, Solarbio, 0.02%) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate. Final processing included hematoxylin counterstaining and light microscopy.

Mouse orthotopic model studies

We bilaterally injected MDA-MB-231 or MCF-7 cells with stable miR-301a overexpression/knockout into the mammary fat pads of 2-month-old female nude mice. Mice were sacrificed at 25th day post-injection. Tumors were excised for RNA/protein extraction, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, or IHC. This study adhered to international (ARRIVE guidelines), national (NIH Guide rev. 1978), and institutional (Harbin Medical University) standards for animal research ethics. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All animal protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (date: September 4, 2023; Number: YJSDW2023-075).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Group comparisons utilized unpaired Student’s t-test (two groups) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (≥ 3 groups). Correlations were determined via Pearson’s coefficient. Each experiment incorporated at least three biological replicates, with P-values < 0.05 deemed statistically significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

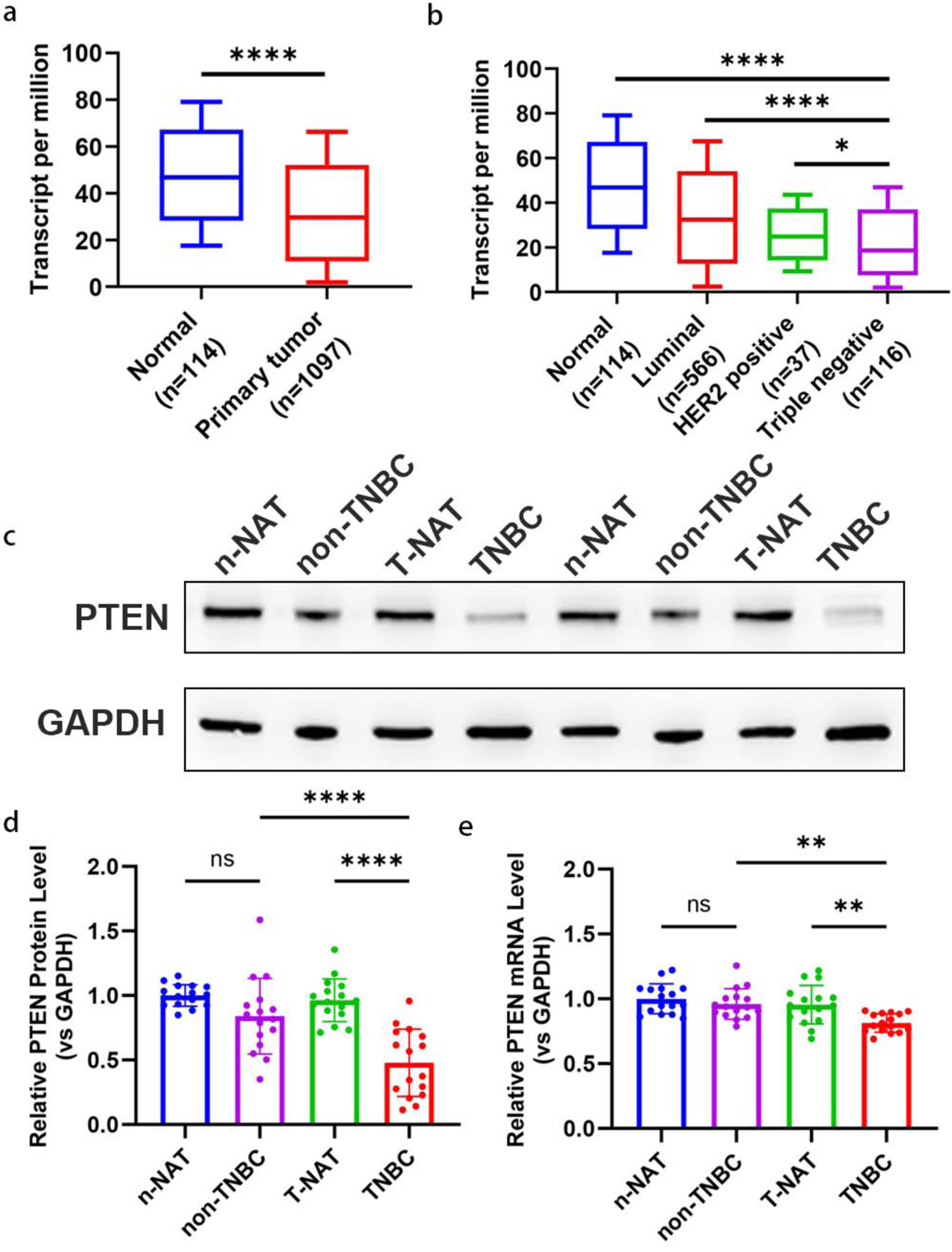

PTEN expression was significantly downregulated in TNBC tumor tissues

On the basis of TCGA database, we analyzed mRNA sequencing results from breast cancer tumor tissues and corresponding normal control tissues. It revealed that levels of PTEN mRNA in tumor tissues were significantly lower than that of normal tissues (Fig. 2a). Meanwhile, PTEN mRNA levels in TNBC tumor tissues were much lower than luminal-positive and HER2-positive subtypes, suggesting that TNBC is the subtype with the lowest PTEN expression (Fig. 2b). To further investigate PTEN levels in TNBC, we obtained 34 pairs of breast cancer tumor tissues and their corresponding normal adjacent tissues (NAT), including 18 pairs from TNBC patients and 16 pairs from non-TNBC patients. Western blot analysis revealed a significant reduction in PTEN protein levels in TNBC tumor tissues in contrast their matched NAT (Fig. 2c, d), while no such reduction was observed in non-TNBC tumor tissues (Fig. 2c, d). Consistently, PTEN mRNA levels also demonstrated a comparable degree of downregulation in TNBC tumor tissues relative to NAT (Fig. 2e) but not in non-TNBC tumor tissues. Our data confirm that PTEN expression is significantly reduced in TNBC as compared to non-TNBC tumors, both at the mRNA and protein levels. This observation is consistent with previous reports on PTEN loss in breast cancer aggressiveness and therapy resistance [21, 34]. In the next phase, we will delineate the molecular mechanisms underlying concurrent suppression of PTEN at transcriptional and translational levels.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Downregulation of PTEN expression in TNBC tissues. (a) The expression level of PTEN mRNA in 1097 breast tumor tissues and 114 normal breast tissues based on the TCGA database. A significant downregulation of PTEN mRNA is observed in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues. (b) Transcript levels of PTEN mRNA were compared across different breast cancer subtypes (luminal, HER2-positive, TNBC) and normal breast tissues using TCGA data. Sample sizes for each group are as follows: Luminal (n = 566), HER2-positive (n = 67), TNBC (n = 116), and normal tissues (n = 114). TNBC tissues display the lowest PTEN mRNA expression compared to other subtypes and normal tissues. (c, d) Representative Western blot images (c) and corresponding densitometric quantification (d) of PTEN protein expression in 34 pairs of breast cancer tumor tissues and their matched adjacent normal tissues. Protein levels were normalized to β-actin as a loading control. (e) PTEN mRNA expression levels were quantified in the same 34 pairs of breast cancer tumor tissues and corresponding normal adjacent tissues using qRT-PCR. Expression levels were normalized to GAPDH as an internal control and are presented as relative fold change. HER-2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer. |

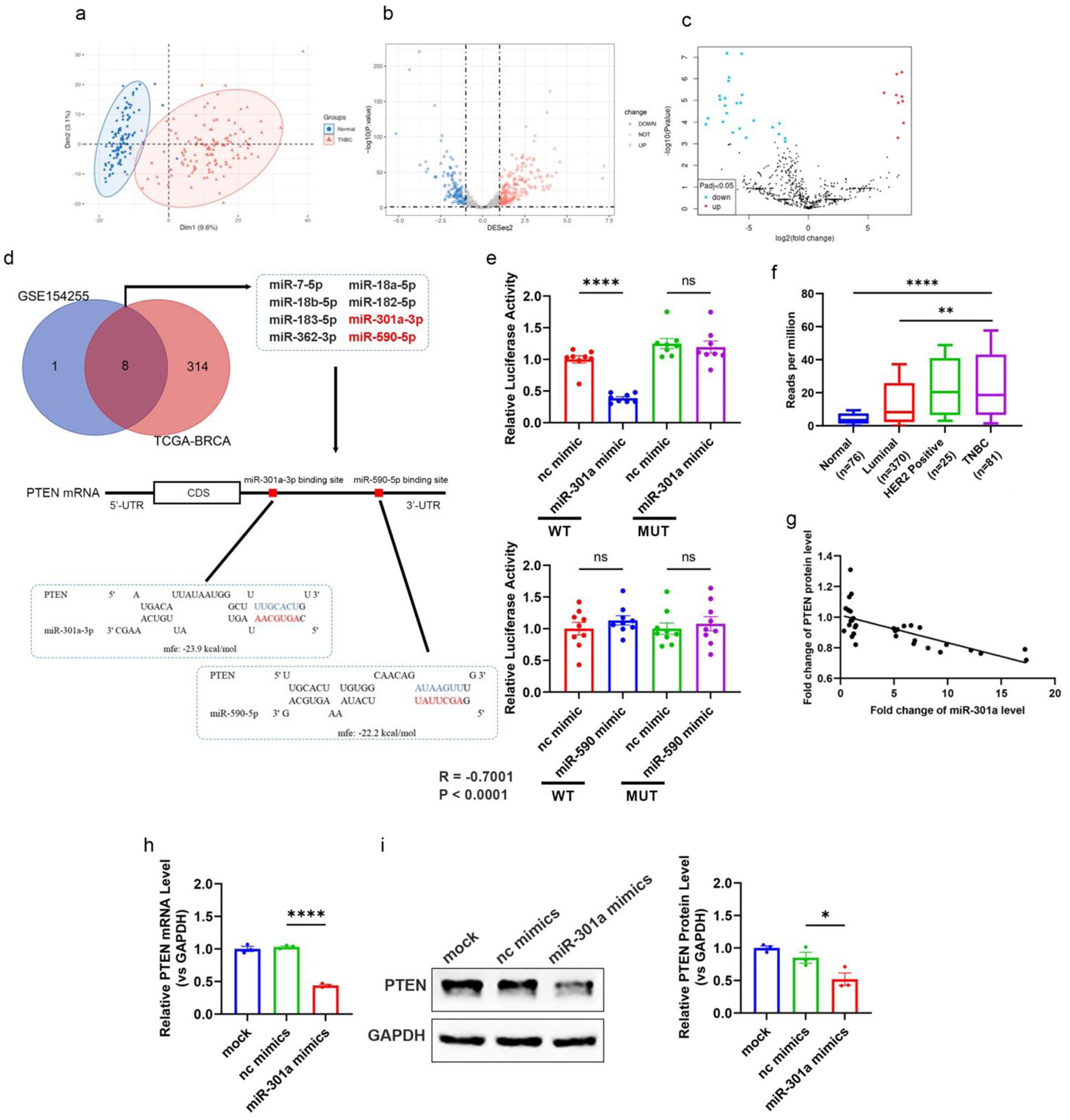

PTEN was a direct target gene of miR-301a-3p, which was overexpressed in TNBC

According to the TCGA-BRCA cohort, we identified 121 TNBC patients and 121 normal tissue samples. Principal component analysis (PCA) dimensionality reduction uncovered significant separation of TNBC samples versus normal samples along principal components (Fig. 3a). Differential expression analysis identified 322 significantly upregulated miRNAs in TNBC samples (Fig. 3b). Additionally, an analysis of the GEO database breast cancer tissue microarray dataset of GSE154255 revealed nine upregulated and 24 downregulated miRNAs in TNBC versus normal tissues (Fig. 3c).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Elevated miR-301a-3p in TNBC directly targets PTEN, contributing to tumor progression. (a) PCA plot showing the distinct clustering of miRNA expression profiles from TNBC tissue samples (n = 116) and normal breast tissue samples (n = 114) within the TCGA-BRCA cohort. The separation indicates significant differences in miRNA expression patterns between TNBC and normal tissues. (b, c) Volcano plots highlighting differentially expressed miRNAs between TNBC and normal breast tissues from two datasets: (b) TCGA-BRCA cohort and (c) GEO database dataset GSE154255. Each dot represents a miRNA, with red indicating upregulation and blue indicating downregulation (fold change > 2 or < -2, adjusted P < 0.05, log2-transformed data). miR-301a-3p is marked as significantly upregulated in both datasets. (d) Venn diagram and schematic showing miRNAs significantly upregulated in both GSE154255 and TCGA-BRCA datasets, with a focus on those predicted to target the 3’-UTR of PTEN. The schematic illustrates the binding site duplex formed between the PTEN 3’-UTR and candidate miRNAs, including miR-301a-3p. (e) The luciferase activities in 293T cells co-transfected with wild type or mutant PTEN 3’-UTR and miRNA or scramble mimics. (f) The transcript level of miR-301a-3p in different subtypes of breast cancer (luminal, Her2 positive, TNBC) and normal breast tissues based on the TCGA database. (g) Pearson’s correlation scatter plot of the fold changes of PTEN mRNA and miR-301a-3p in human TNBC tissue pairs (n = 18). (h) PTEN mRNA expression in MCF-7 cells after transfection with miR-301a-3p mimic. (i) Western blot analysis and densitometric analysis showing PTEN protein levels in MCF-7 cells after transfection with miR-301a-3p mimic. GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus; PCA: principal component analysis; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer. |

By integrating these datasets, we identified eight candidate miRNAs that were significantly upregulated in TNBC tissues, that are, miR-7-5p, miR-18a-5p, miR-18b-5p, miR-182-5p, miR-183-5p, miR-301a-3p, miR-362-3p, and miR-590-5p (Fig. 3d). We then examined potential interactions between PTEN mRNA and the eight upregulated miRNAs with RNAhybrid. The results suggested that miR-590-5p and miR-301a-3p could directly bind to the 3'-UTR of PTEN mRNA (Fig. 3d). Luciferase reporter assays were designed to test binding. Predicted sites were cloned into plasmid 3'-UTRs to generate PTEN-WT and PTEN-MUT (seed sequence mutants). HEK293T cells were co-transfected with these constructs plus miR-301a-3p mimics or negative control oligonucleotides. Luciferase assays indicated that miR-301a-3p specifically suppressed WT vector activity, whereas miR-590-5p showed no significant effect on either construct (Fig. 3e). This indicates that miR-301a-3p directly binds to the 3'-UTR of PTEN and inhibits its expression, whereas miR-590-5p does not. Based on TCGA data, we found that miR-301a-3p levels in TNBC were significantly higher than in luminal-positive and HER2-positive subtypes (Fig. 3f). Further, we analyzed the correlation between miR-301a-3p and PTEN expression in TNBC tissues by RT-qPCR, which revealed a strong inverse correlation (R = -0.7001) (Fig. 3g). To further confirm the regulatory role of miR-301a-3p on PTEN, we transfected the miR-301a-3p low-expressing non-TNBC cell line MCF-7 with miR-301a-3p mimics. Results showed that at both transcriptional and translational levels, PTEN was markedly downregulated in miR-301a-3p-transfected cells versus controls (Fig. 3h, i). These findings confirm that miR-301a-3p suppresses PTEN expression post-transcriptionally, contributing to the regulation of TNBC progression.

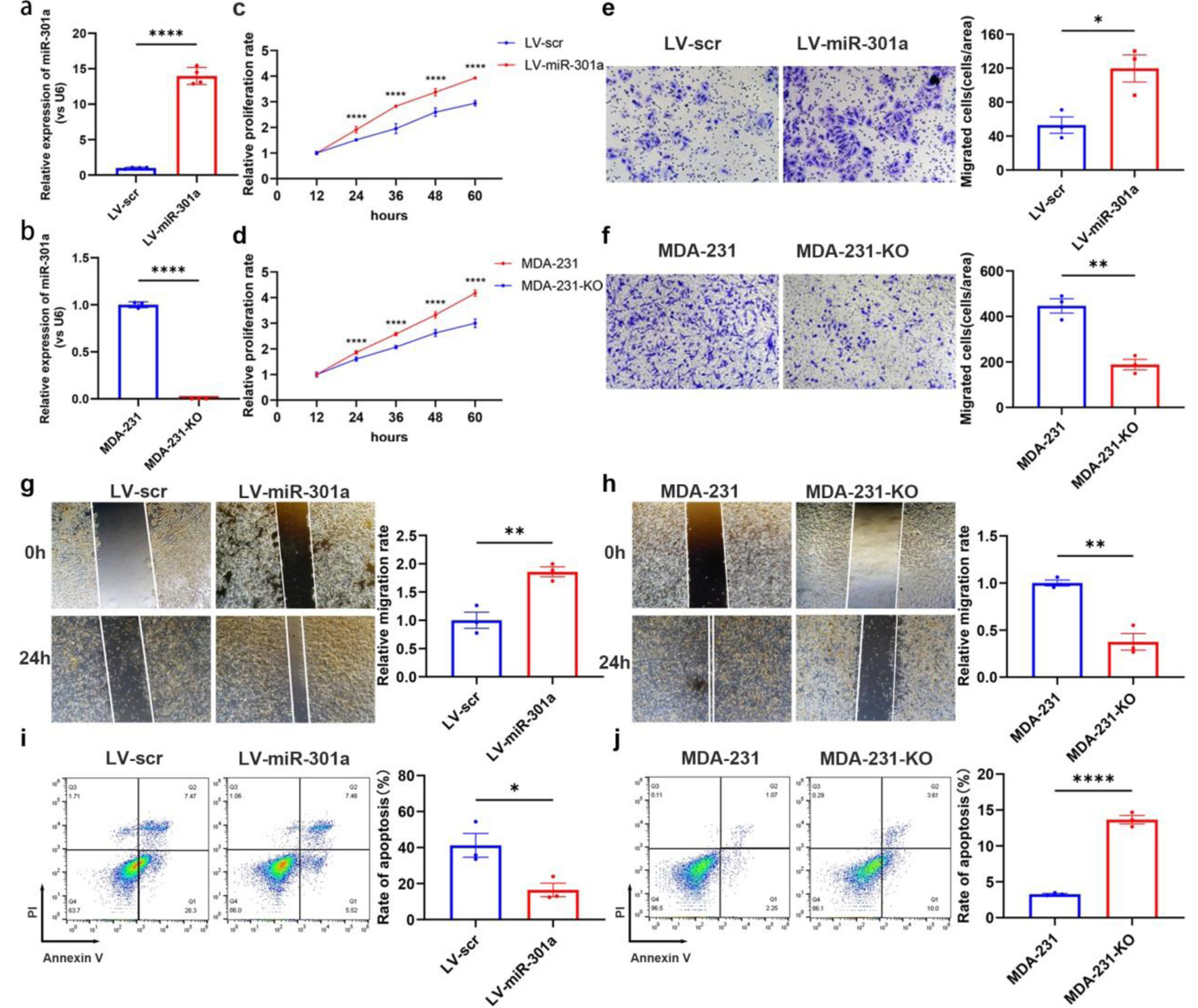

MiR-301a-3p promoted proliferative, migratory, and invasive capacities while inhibiting apoptosis in breast cancer cells

We established a stable cell line overexpressing miR-301a-3p (LV-miR-301a) in the non-TNBC MCF-7 cell line using lentiviral infection. Additionally, we employed CRISPR-Cas9 technology to knockout miR-301a-3p in the MDA-MB-231 TNBC cell line, which naturally expresses high levels of miR-301a-3p, resulting in the MDA-231-KO cell line. The efficiencies of overexpression and knockout were confirmed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 4a, b). To probe and quantify miR-301a-3p-driven proliferation changes, CCK-8 assays were systematically performed. Longitudinal CCK-8 profiling revealed accelerated growth kinetics in LV-miR-301a cells compared to LV-scramble counterparts (Fig. 4c). In contrast, the MDA-231-KO cell line showed reduced proliferation relative to the parental MDA-MB-231 cell line (Fig. 4d). Transwell and wound healing assays revealed that invasion (Fig. 4e) and migration (Fig. 4g) abilities significantly increased in LV-miR-301a cells as compared to the LV-scr control group. Conversely, the depletion of miR-301a-3p in MDA-231-KO cells resulted in decreased invasion (Fig. 4f) and migration (Fig. 4h) capabilities. Significantly decreased apoptotic fractions were observed in LV-miR-301a cells relative to LV-scr controls (Fig. 4i), whereas MDA-231-KO cells exhibited elevated apoptosis compared to wild-type counterparts (Fig. 4j).

Click for large image | Figure 4. MiR-301a-3p enhances proliferation, migration and invasion but suppresses apoptosis in breast cancer cells. (a) qRT-PCR analysis confirming the efficiency of stable miR-301a-3p overexpression in the MCF-7 cell line (LV-miR-301a). (b) qRT-PCR analysis confirming the knockout efficiency of miR-301a-3p in the MDA-MB-231 cell line (MDA-231-KO). (c) CCK-8 assay showing the proliferation rate of LV-miR-301a cells compared to LV-scr cells. (d) CCK-8 assay showing the proliferation rate of MDA-231-KO cells compared to MDA-MB-231 cells. (e) Transwell assay showing the invasion capability of LV-miR-301a cells compared to LV-scr cells. (f) Transwell assay showing the invasion capability of MDA-231-KO cells compared to MDA-MB-231 cells. (g) Wound healing assay revealing the migration capability of LV-miR-301a cells compared to LV-scr cells. (h) Wound healing assay revealing the migration capability of MDA-231-KO cells compared to MDA-MB-231 cells. (i) Analysis of apoptosis in LV-miR-301a cells and LV-scr cells. (j) Analysis of apoptosis in MDA-231-KO cells and MDA-MB-231 cells. Left panel: representative image; Right panel: quantitative analysis. CCK-8: cell counting kit-8; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. |

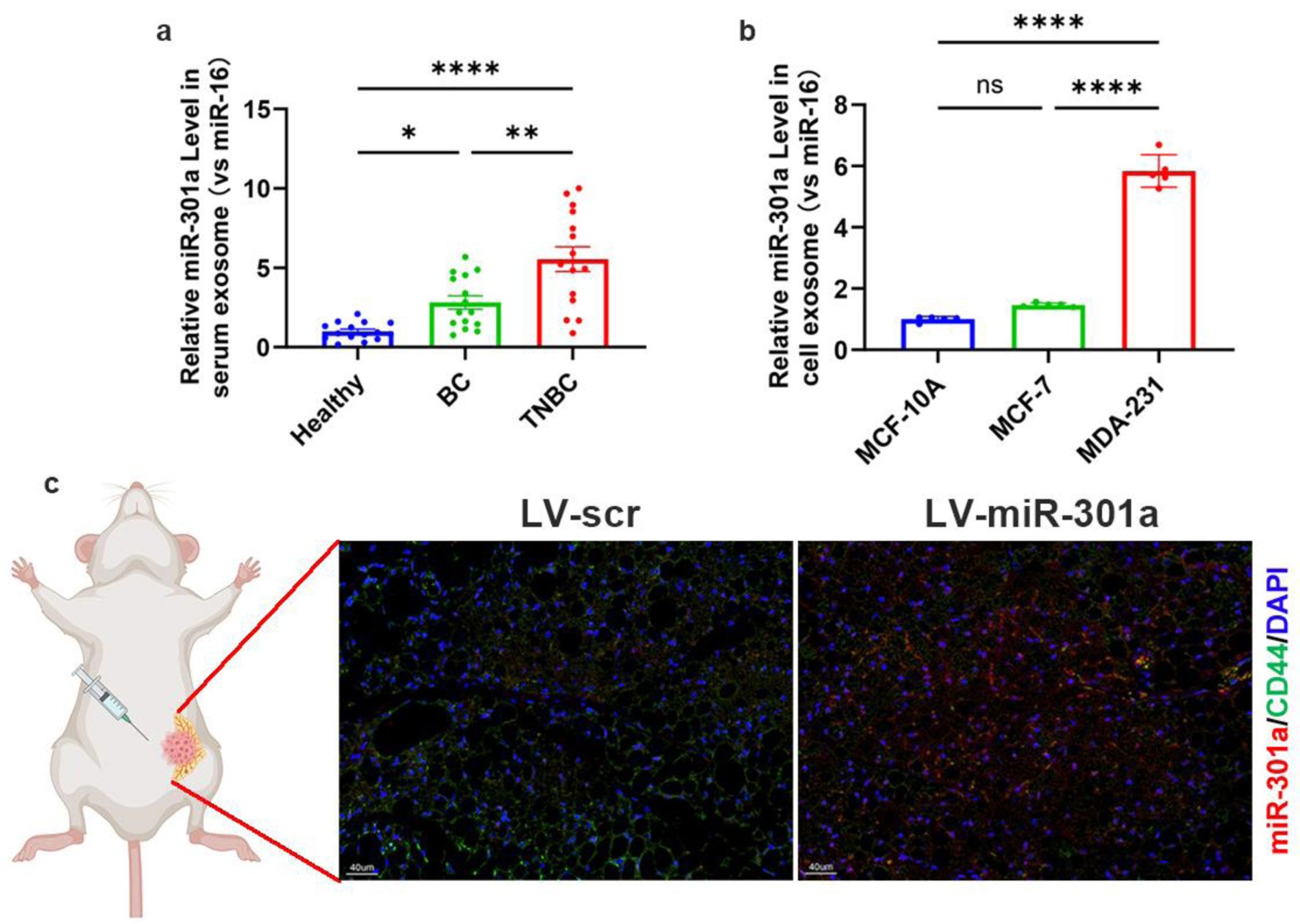

Elevated miR-301a-3p in TNBC exosomes was internalized by peritumoral ADSCs, mediating functional regulation

Through exosome-mediated trafficking, tumor cells actively export regulatory miRNAs to the extracellular milieu, functionally reprogramming the TME [35, 36]. To determine whether miR-301a-3p is secreted extracellularly, we isolated exosomes from the serum of healthy individuals, non-TNBC patients, and TNBC patients. Quantification of miR-301a-3p levels in these exosomes revealed that its abundance was significantly higher in the serum exosomes of TNBC patients compared to those of non-TNBC patients and healthy controls (Fig. 5a). This finding suggests that elevated miR-301a-3p in the serum of TNBC patients may originate from tumor tissue secretion. Furthermore, we isolated exosomes from the culture supernatants of different cell lines: MDA-MB-231 (metastatic TNBC), MCF-7 (ER-positive adenocarcinoma), and MCF-10A (normal mammary epithelium). Markedly increased relative expression of miR-301a-3p was detected in MDA-MB-231 exosomes compared to the two non-TNBC cell line-derived exosomes through systematic expression analysis (Fig. 5b). To investigate the in vivo effects of miR-301a-3p on the TME, particularly its influence on ADSCs, we established orthotopic breast tumor models in nude mice using LV-miR-301a and LV-scr cell lines. In situ hybridization indicated that ADSCs within peritumoral tissues had significantly higher levels of miR-301a-3p in the LV-miR-301a group compared to the LV-scramble group. Furthermore, we observed pronounced co-localization of miR-301a-3p with CD44-positive ADSCs, demonstrating that miR-301a-3p can be secreted by tumor cells and subsequently internalized by ADSCs in the peritumoral microenvironment (Fig. 5c). We observed that serum exosomal miR-301a-3p levels were significantly elevated in TNBC patients compared to other breast cancer subtypes, indicating tumor-secreted exosomal packaging of this miRNA. In murine models, we further confirmed that tumor-derived exosomal miR-301a-3p targets ADSCs within the TME. Consequently, our subsequent investigations will characterize the functional impact of exosomal miR-301a-3p on ADSCs.

Click for large image | Figure 5. TNBC exosomes deliver upregulated miR-301a-3p to peritumoral ADSCs. (a) Quantification of miR-301a-3p levels in serum-derived exosomes from healthy donors, non-TNBC patients, and TNBC patients. (b) qRT-PCR analysis of relative miR-301a-3p expression in exosomes derived from MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and MCF-10A cell lines. (c) In situ hybridization for miR-301a-3p and immunofluorescence for CD44 in peritumoral tissues from orthotopic tumor models. ADSCs: adipose-derived stem cells; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer. |

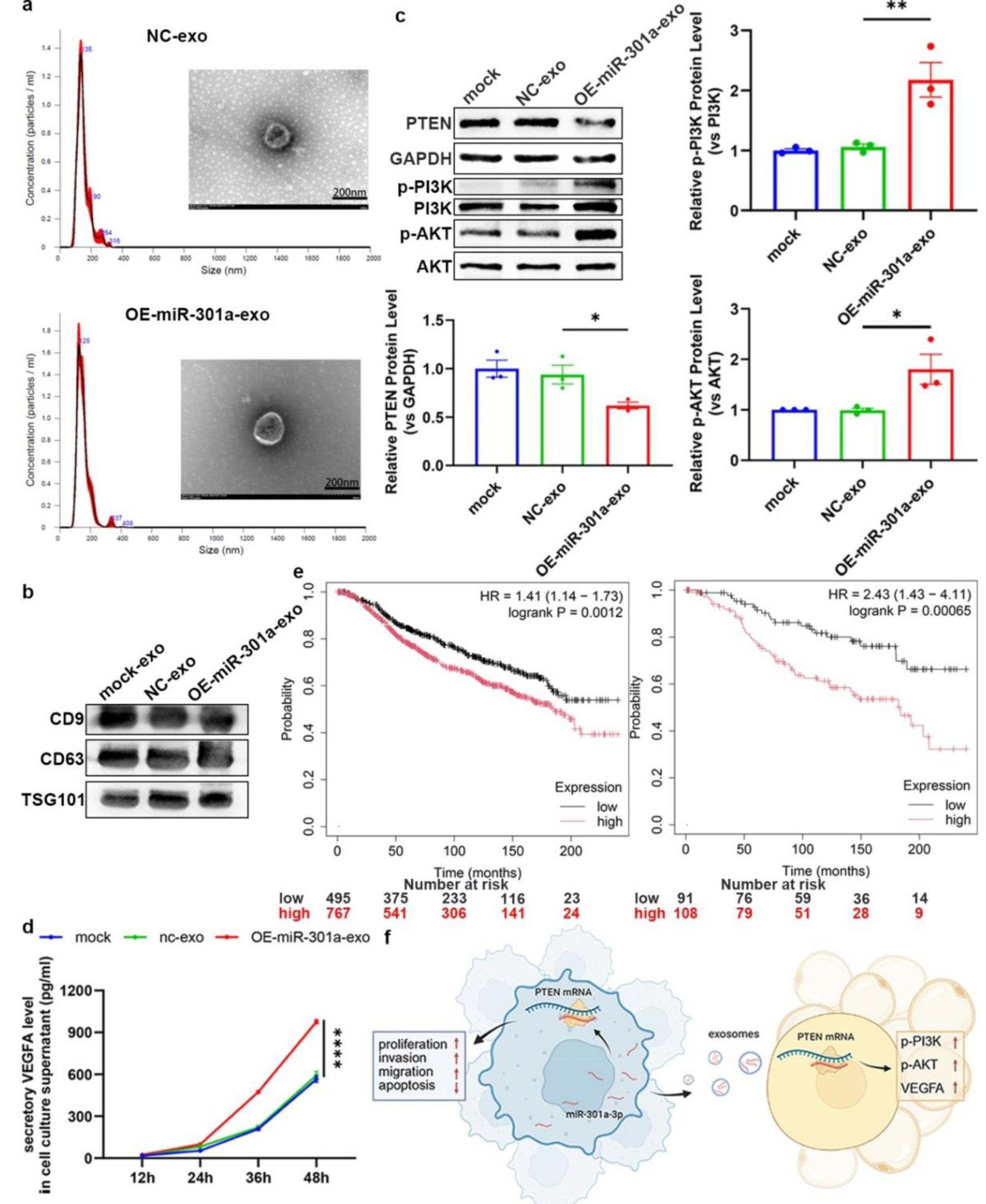

Exosomal miR-301a-3p modulates TME remodeling through PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway activation in ADSCs

Using differential centrifugation, exosomes were purified from LV-301a or LV-scr cell supernatants. Their sizes were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS), morphology was imaged via transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 6a), and the molecular markers were validated with western blot (Fig. 6b). ADSCs treated with miR-301a-3p (OE-exosomes) overexpressed LV-301a exosomes exhibited significantly reduced PTEN protein levels relative to those treated with LV-scr exosomes (NC-exosomes) (Fig. 6c). Previous research has demonstrated that PTEN inhibits VEGFA expression in tumor tissues through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [37, 38]. Accordingly, we evaluated the phosphorylation status of PI3K/AKT in ADSCs post-exosome treatment. Notably, co-culture with OE-exosomes led to a marked increase in PI3K/AKT phosphorylation levels in ADSCs in contrast to the NC-exosome group (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, VEGFA secretion into the ADSC culture medium was significantly elevated following OE-exosome treatment (Fig. 6d). Moreover, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the patients of breast cancer with a high level of miR-301a-3p had worse outcome than high ones (Fig. 6e) in TCGA database, which also indicates the prognosis value of miR-301a-3p in breast cancer patients. Collectively, these findings indicate that miR-301a-3p not only enhanced tumor cell proliferation and invasion but also secreted into the TME via exosomes, where it is internalized by ADSCs, resulting in increased VEGFA production (Fig. 6f). This section confirms that exosomal miR-301a-3p modulates the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway in ADSCs to regulate VEGFA secretion at the cellular level. Considering that in vitro evidence alone is insufficient, we will employ murine in vivo models to investigate the impact of miR-301a-3p on tumor progression through complementary approaches (intratumoral injection of miR-301a-3p-overexpressing adenovirus and orthotopic implantation of tumor cells with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated miR-301a-3p knockout). These experiments will simultaneously validate the involvement of the aforementioned signaling pathway while assessing tumorigenic effects.

Click for large image | Figure 6. Exosomal miR-301a-3p from TNBC cells modulates the TME through regulating the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway in ADSC. (a) DLS analysis showing the size distribution of exosomes isolated from the culture medium of LV-301a or LV-scr cells. TEM image showing the typical cup-shaped morphology of isolated exosomes. (b) Western blot analysis of exosomal protein markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, TSG101). (c) Representative western blot and densitometric analysis of PTEN protein levels in ADSCs following treatment with exosomes from miR-301a-3p-overexpressing cells (OE-exosomes) or control cells (NC-exosomes). (d) ELISA for VEGFA in the culture medium of ADSCs following treatment with OE-exosomes or NC-exosomes. (e) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of all (left panel) and untreated (right panel) breast cancer patients from the TCGA database, stratified by high versus low miR-301a-3p expression. (f) Schematic model illustrating the proposed mechanism of exosomal miR-301a-3p transfer and its downstream signaling. ADSC: adipose-derived stem cell; DLS: dynamic light scattering; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; TME: tumor microenvironment; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer; VEGFA: vascular endothelial growth factor A. |

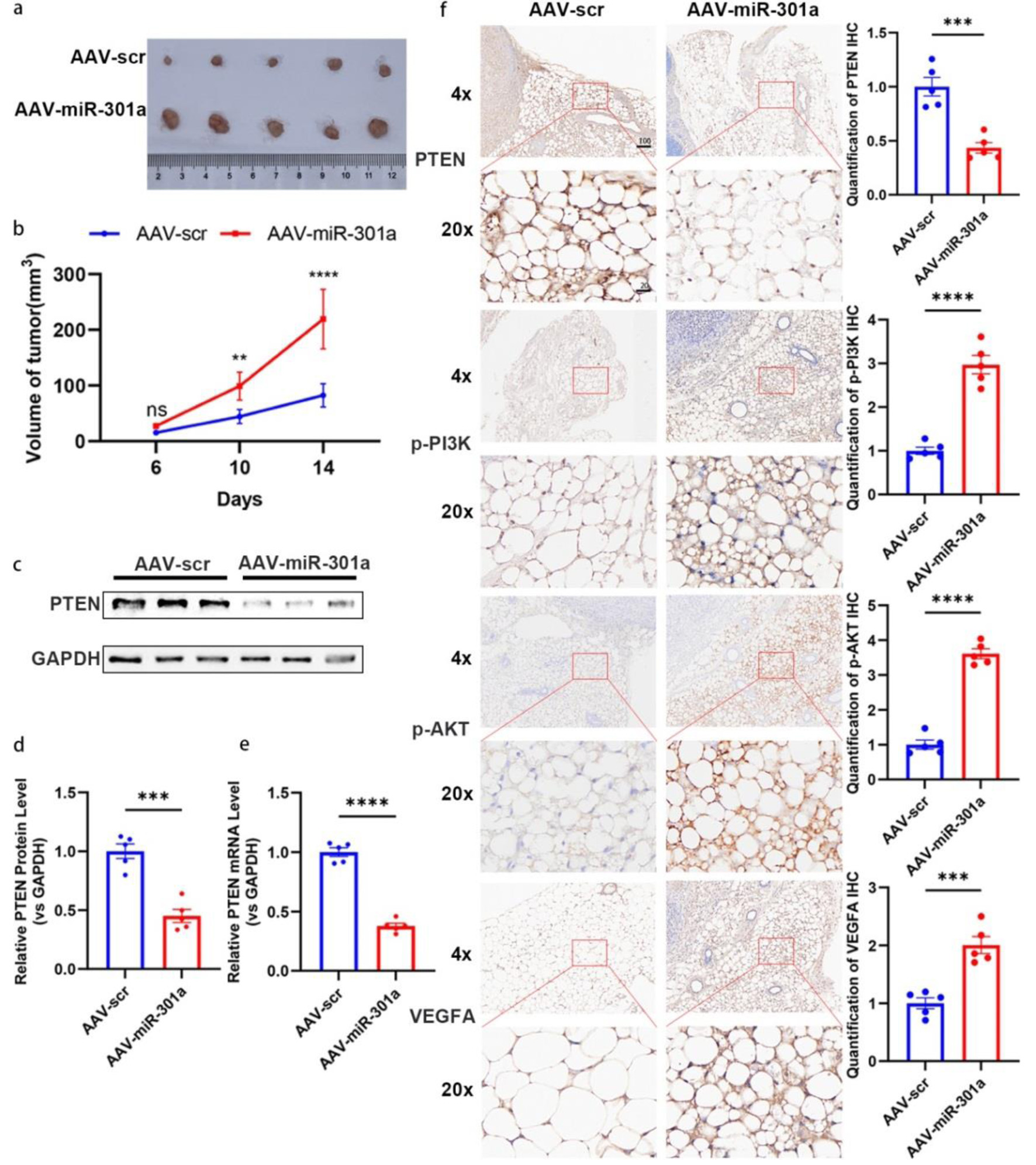

MiR-301a-3p driven tumor growth via PTEN suppression-mediated PI3K/AKT activation and subsequent VEGFA secretion

To further validate the contribution of miR-301a-3p to TNBC progression in vivo, we established orthotopic breast tumor models in nude mice using the MCF-7 cell line. On day 4 post-implantation, mice received intratumoral injection of AAV overexpressing miR-301a-3p (AAV-miR-301a) or scramble sequence (AAV-scr). As shown in Figure 7a and b, the tumor volume of the AAV-miR-301a group is much larger than that in the AAV-scr group. Western blot analysis of tumor tissues indicates decreased protein and mRNA levels of PTEN (Fig. 7c-e). Immunohistochemical staining of peritumoral adipose tissues show a significant reduction in PTEN expression in the AAV-miR-301a group (Fig. 7f). IHC analysis of the peritumoral adipose tissues further confirms the activation of the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway, resulting in enhanced VEGFA expression and secretion (Fig. 7f).

Click for large image | Figure 7. MiR-301a-3p promotes tumor growth in vivo. (a, b) Orthotopic MCF-7 mouse models (n = 6 per group) were subjected to intra-tumoral injection with adeno-associated virus expressing miR-301a-3p (AAV-miR-301a) or scramble control (AAV-scr). Tumor volumes were measured for 14 days post-injection. (a) Representative photographs of excised tumors from each group at the endpoint (day 14). (b) Tumor growth curves depicting the volume of tumors (measured in mm3) over time in, and data are presented as mean ± SEM, showing significantly enhanced growth in the AAV-miR-301a group compared to AAV-scr. (c, d) PTEN expression analysis in tumor tissues: Representative Western blot images (c) and densitometric quantification (d) of PTEN protein levels in tumor tissues harvested from mice treated with AAV-miR-301a or AAV-scr (n = 5 per group). Protein expression is normalized to β-actin as a loading control and presented as relative expression (mean ± SEM), showing a significant reduction in PTEN protein in the AAV-miR-301a group compared to AAV-scr. (e) qRT-PCR analysis of PTEN mRNA levels in the same tumor tissues, normalized to GAPDH as an internal control and presented as relative fold change (mean ± SEM, n = 5 per group), demonstrating significant downregulation in the AAV-miR-301a group compared to AAV-scr. (f) Representative IHC images showing staining for PTEN, phosphorylated PI3K (p-PI3K), phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT), and VEGFA in peritumoral adipose tissues from mice treated with AAV-miR-301a or AAV-scr (n = 5 per group). Staining intensity was quantified using ImageJ software, with data indicating decreased PTEN expression and increased p-PI3K, p-AKT, and VEGFA expression in the AAV-miR-301a group compared to AAV-scr. Scale bars represent 50 µm. IHC: immunohistochemistry; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; SEM: standard error of the mean; VEGFA: vascular endothelial growth factor A. |

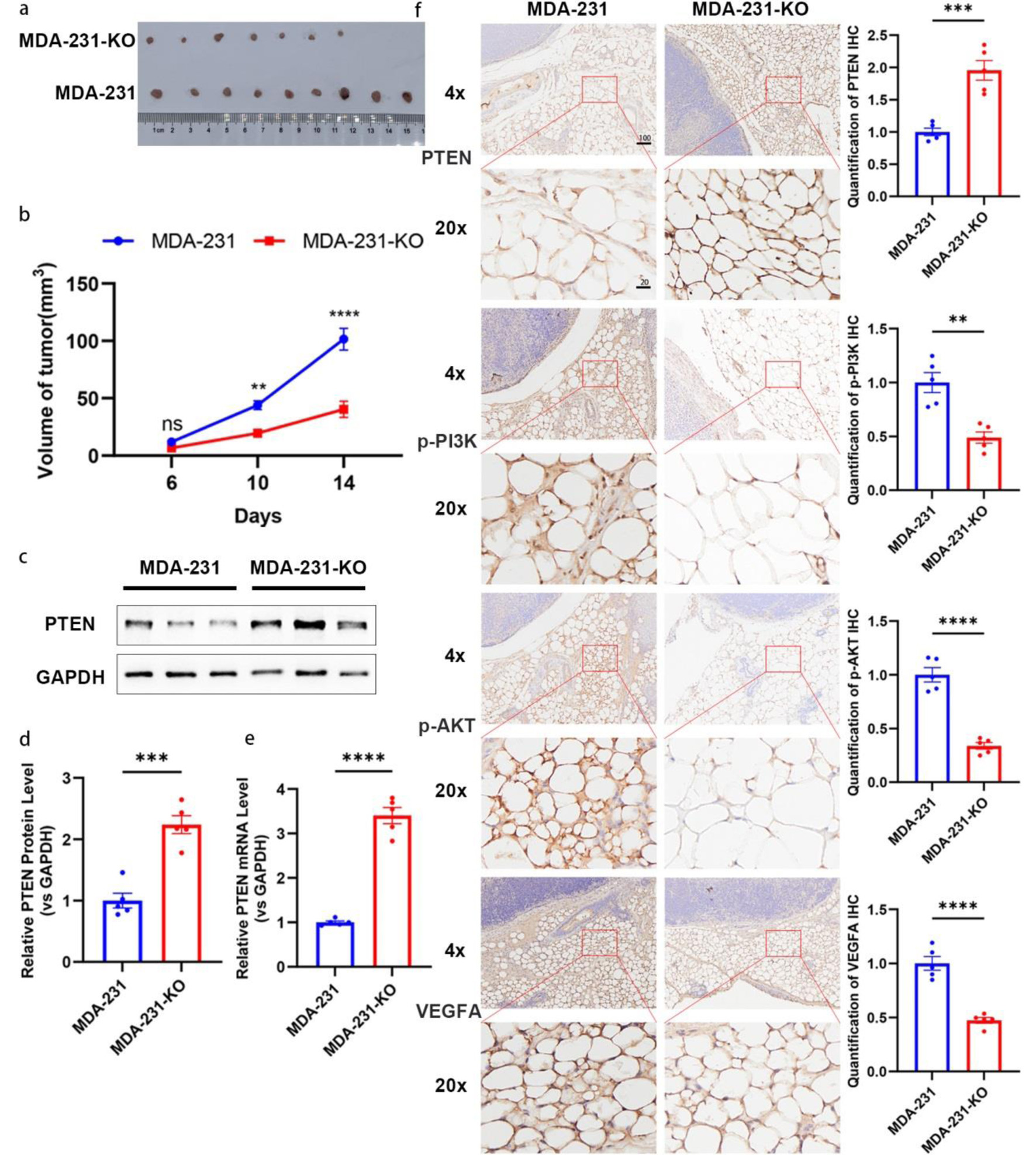

Genetic ablation of miR-301a-3p suppresses tumorigenesis via PTEN reactivation

On the other hand, we further validated whether depletion of miR-301a-3p could inhibit tumor formation by establishing a similar orthotopic model with MDA-MB-231 or MDA-231-KO cell lines. As expected, the tumor volume and proliferation rate were dramatically decreased in the MDA-231-KO group (Fig. 8a, b). Molecular analysis also showed the restoration of PTEN expression (Fig. 8c-e), which led to the deactivation of the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway and downregulated VEGFA level in peritumoral adipose tissues (Fig. 8f).

Click for large image | Figure 8. Depletion of miR-301a-3p inhibits tumor growth in vivo. (a, b) Tumor growth curves and representative images of tumors from an orthotopic mouse model established with MDA-MB-231 (MDA-231) or miR-301a-3p knockout (MDA-231-KO) cells. (a) Representative photographs of excised tumors from each group at the endpoint (day 14). (b) Tumor growth curves depicting the volume of tumors (measured in mm3) over time in, and data are presented as mean ± SEM, showing significantly enhanced growth in the MDA-231 group compared to MDA-231-KO group. (c, d) PTEN expression analysis in tumor tissues: representative Western blot images (c) and densitometric quantification (d) of PTEN protein levels in tumor tissues harvested from mice implanted with MDA-231 or MDA-231-KO cells (n = 5 per group). Protein expression is normalized to β-actin as a loading control and presented as relative expression (mean ± SEM), showing a significant increase in PTEN protein in the MDA-231-KO group compared to MDA-231. (e) qRT-PCR analysis of PTEN mRNA levels in the same tumor tissues, normalized to GAPDH as an internal control and presented as relative fold change (mean ± SEM, n = 5 per group), demonstrating significant upregulation in the MDA-231-KO group compared to MDA-231. (f) Representative IHC images showing staining for PTEN, p-PI3K, p-AKT, and VEGFA in peritumoral adipose tissues from mice implanted with MDA-231 or MDA-231-KO cells (n = 5 per group). Staining intensity was quantified using ImageJ software, with data indicating increased PTEN expression and decreased p-PI3K, p-AKT, and VEGFA expression in the MDA-231-KO group compared to MDA-231 group. Scale bars represent 50 µm. IHC: immunohistochemistry; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; SEM: standard error of the mean; VEGFA: vascular endothelial growth factor A. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The clinical management of TNBC poses significant therapeutic hurdles owing to its heightened aggressiveness, absence of targeted treatment options, and unfavorable prognosis relative to other breast cancer subtypes [39, 40]. In this study, we identified miR-301a-3p as a critical oncogenic regulator in TNBC and elucidated its dual role in tumor cells and the TME through the suppression of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Previous studies mainly focused on tumor-intrinsic mechanisms of miR-301a, for example, Song et al demonstrated that forms a feedback loop with CIP2A, promoting cell proliferation and invasion in TNBC [41]. Our findings reveal a previously underappreciated mechanism that miR-301a-3p contributes to TNBC progression by modulating both cell-intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, and provide a compelling rationale for considering miR-301a-3p as a therapeutic target and prognostic biomarker.

We validated significant downregulation of PTEN in TNBC versus non-TNBC tumors at both transcriptional (mRNA) and translational (protein) levels, corroborating established associations between PTEN loss and heightened breast cancer aggressiveness/therapeutic resistance [21, 34]. Importantly, we demonstrated that miR-301a-3p directly targets the 3'-UTR of PTEN mRNA, suppressing its expression in a post-transcriptional manner. This direct interaction was validated by luciferase reporter assays, inverse correlation analyses, and functional experiments involving miR-301a-3p overexpression and knockout. These results expanded upon prior work describing miR-301a family members as oncogenic miRNAs in various cancers, and identified PTEN as a novel and functionally important downstream target in TNBC.

Functionally, the change of miR-301a-3p levels significantly altered TNBC cell destiny. Ectopic miR-301a-3p expression potentiated oncogenic phenotypes - proliferation, migration, and invasion - while suppressing apoptosis; conversely, CRISPR/Cas9 mediated miR-301a-3p ablation reversed these effects. These findings underscored the central role of miR-301a-3p in promoting malignant phenotypes and further supported its characterization as an oncogenic miRNA.

Beyond tumor cell-autonomous effects, our study provided a novel insight into how tumor-derived exosomal miR-301a-3p reshaped the TME, particularly through its action on ADSCs. We showed that miR-301a-3p was packaged into exosomes by TNBC cells and transferred to ADSCs, leading to suppression of PTEN, activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, and subsequent upregulation of VEGFA secretion. This paracrine signaling loop aligned with previous studies that PTEN inhibits angiogenic signaling through the PI3K/AKT axis [38, 42] and exosomal miRNAs can modulate stromal cell function to promote tumor progression [17, 43]. In vivo models further validated these findings, showing that modulation of miR-301a-3p levels significantly alters tumor growth, PTEN expression, and VEGFA production in both tumor and peritumoral tissues. These data suggested that miR-301a-3p acted as a central mediator linking tumor cells and the surrounding stroma via exosome-based communication, thereby promoting an angiogenic and growth-permissive microenvironment. Such mechanisms highlighted the complexity of TNBC biology and the importance of targeting both tumor-intrinsic pathways and stromal crosstalk in future therapeutic strategies. In addition, the effects of exosomal miRNAs and PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling can be highly context-dependent, with some studies reporting divergent outcomes depending on tumor type, stromal composition, or specific miRNA cargo. For instance, exosomal miR-9 and miR-92-3p have been shown to exert anti-angiogenic effects in different cancer models [44, 45], while PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling outcomes may vary based on upstream regulators or cellular context [37]. This suggests that while our findings highlight a pro-angiogenic role for miR-301a-3p in TNBC, alternative mechanisms or opposing effects may occur under different conditions.

From a clinical perspective, miR-301a-3p overexpression in tumor tissue and patient serum served as a negative prognosticator, nominating it as a candidate biomarker for TNBC disease progression. Zheng et al reported that elevated miR-301a expression is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients, including those with TNBC [30]. Similarly, Yu et al highlighted the correlation between miR-301a upregulation and poor prognosis specifically in TNBC, reinforcing the clinical relevance of miR-301a as a prognostic biomarker [46]. In accordance with these findings, our research also showed worse outcomes in patients with high miR-301a-3p levels and provided mechanistic depth by identifying PTEN as a direct target of miR-301a-3p and validating its oncogenic effects through in vivo mouse models. Thus, our study not only corroborated the established oncogenic and prognostic significance of miR-301a in TNBC but also introduces novel insights into its TME interactions and molecular targets. Given its multifaceted role in driving tumor progression and modifying the microenvironment, miR-301a-3p may also represent a promising target for therapeutic intervention. Future studies should explore the efficacy of miR-301a-3p inhibition in preclinical models and assess its synergy with existing chemotherapy or immune checkpoint blockade.

Although this study provides significant insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of TNBC, certain limitations arising from resource constraints must be acknowledged. Firstly, the relatively small sample size may limit the statistical power and generalizability of our findings, necessitating validation in larger cohorts. Secondly, our results have not been validated through high-throughput sequencing methods across multicenter clinical samples, which could provide deeper molecular insights and confirm the reproducibility of our observations. Addressing these constraints in future research will enhance the robustness and broader applicability of our findings.

Conclusions

PTEN downregulation was a prevalent phenotype in TNBC. This study attributed this phenomenon primarily to miR-301a-3p, which directly targeted PTEN and suppressed its expression. Furthermore, miR-301a-3p drives TNBC progression through dual mechanisms - autonomous promotion of proliferation/migration and exosome-mediated reprogramming of ADSCs, resulting in PTEN suppression, PI3K/AKT activation, and VEGFA secretion. This interaction not only enhanced tumor progress but also underscored the complex interplay between tumor cells and their microenvironment. In vivo experiments further confirmed that modulating miR-301a-3p levels substantially influenced tumor growth, while reaffirming that miR-301a-3p promoted tumor progression by suppressing PTEN, activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, and enhancing VEGFA secretion. Given the critical role of miR-301a-3p in tumor progression, our findings provided a foundation for exploring this molecule as a potential therapeutic target and prognosis biomarker in TNBC.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This work was supported by grants from the Excellent Postdoctoral Program of Jiangsu Province (2023ZB697) and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20230786), and from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32401274). The APC was funded by HL.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: HYL, GYL, and ZF; validation: HYL, GYL, WLL, and YW; formal analysis: HYL, GYL, and BYF; investigation: HYL, QGD, YTZ, ZKX, and HC; resources: HYL and ZF; writing - original draft preparation: HYL, GYL, and ZF; writing - review and editing: HYL, WLL, BYF, and ZF; visualization: HYL; supervision: HYL, ZF, XC, and JGZ; project administration: HYL and JGZ; funding acquisition: ZF, XC, and JGZ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author, Jian Guo Zhang or first author, Hai Yun Lin, upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

ADSCs: adipose-derived stem cells; TME: tumor microenvironment; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer; VEGFA: vascular endothelial growth factor A

| References | ▴Top |

- Tang W, Xia M, Liao Y, Fang Y, Wen G, Zhong J. Exosomes in triple negative breast cancer: From bench to bedside. Cancer Lett. 2022;527:1-9.

doi pubmed - Dvir K, Giordano S, Leone JP. Immunotherapy in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(14).

doi pubmed - Singh S, Numan A, Maddiboyina B, Arora S, Riadi Y, Md S, Alhakamy NA, et al. The emerging role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26(7):1721-1727.

doi pubmed - Wang X, Li X, Dong T, Yu W, Jia Z, Hou Y, Yang J, et al. Global biomarker trends in triple-negative breast cancer research: a bibliometric analysis. Int J Surg. 2024;110(12):7962-7983.

doi pubmed - Li Y, Zhang H, Merkher Y, Chen L, Liu N, Leonov S, Chen Y. Recent advances in therapeutic strategies for triple-negative breast cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):121.

doi pubmed - Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(15 Pt 1):4429-4434.

doi pubmed - Yin L, Duan JJ, Bian XW, Yu SC. Triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtyping and treatment progress. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22(1):61.

doi pubmed - Badve S, Dabbs DJ, Schnitt SJ, Baehner FL, Decker T, Eusebi V, Fox SB, et al. Basal-like and triple-negative breast cancers: a critical review with an emphasis on the implications for pathologists and oncologists. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(2):157-167.

doi pubmed - Bianchini G, De Angelis C, Licata L, Gianni L. Treatment landscape of triple-negative breast cancer - expanded options, evolving needs. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(2):91-113.

doi pubmed - Torres Quintas S, Canha-Borges A, Oliveira MJ, Sarmento B, Castro F. Special issue: nanotherapeutics in women's health emerging nanotechnologies for triple-negative breast cancer treatment. Small. 2024;20(41):e2300666.

doi pubmed - Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, De Ugarte DA, Huang JI, Mizuno H, Alfonso ZC, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(12):4279-4295.

doi pubmed - Sun R, Gao DS, Shoush J, Lu B. The IL-1 family in tumorigenesis and antitumor immunity. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86(Pt 2):280-295.

doi pubmed - Kang S, Narazaki M, Metwally H, Kishimoto T. Historical overview of the interleukin-6 family cytokine. J Exp Med. 2020;217(5).

doi pubmed - Saraiva M, Vieira P, O'Garra A. Biology and therapeutic potential of interleukin-10. J Exp Med. 2020;217(1).

doi pubmed - Jiang W, Zhang J, Zhang X, Fan C, Huang J. VAP-PLGA microspheres (VAP-PLGA) promote adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs)-induced wound healing in chronic skin ulcers in mice via PI3K/Akt/HIF-1alpha pathway. Bioengineered. 2021;12(2):10264-10284.

doi pubmed - Apte RS, Chen DS, Ferrara N. VEGF in signaling and disease: beyond discovery and development. Cell. 2019;176(6):1248-1264.

doi pubmed - Freese KE, Kokai L, Edwards RP, Philips BJ, Sheikh MA, Kelley J, Comerci J, et al. Adipose-derived stems cells and their role in human cancer development, growth, progression, and metastasis: a systematic review. Cancer Res. 2015;75(7):1161-1168.

doi pubmed - Zhao C, Wu M, Zeng N, Xiong M, Hu W, Lv W, Yi Y, et al. Cancer-associated adipocytes: emerging supporters in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):156.

doi pubmed - Zhang Z, Lin F, Wu W, Jiang J, Zhang C, Qin D, Xu Z. Exosomal microRNAs in lung cancer: a narrative review. Transl Cancer Res. 2024;13(6):3090-3105.

doi pubmed - Pandolfi PP. Breast cancer—loss of PTEN predicts resistance to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(22):2337-2338.

doi pubmed - Hopkins BD, Hodakoski C, Barrows D, Mense SM, Parsons RE. PTEN function: the long and the short of it. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39(4):183-190.

doi pubmed - Cunha ERK, Ying W, Olefsky JM. Exosome-mediated impact on systemic metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol. 2024;86:225-253.

doi pubmed - Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281-297.

doi pubmed - He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5(7):522-531.

doi pubmed - Carrington JC, Ambros V. Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science. 2003;301(5631):336-338.

doi pubmed - Dou J, Tu D, Zhao H, Zhang X. LncRNA PCAT18/miR-301a/TP53INP1 axis is involved in gastric cancer cell viability, migration and invasion. J Biochem. 2020;168(5):547-555.

doi pubmed - Qi B, Wang Y, Zhu X, Gong Y, Jin J, Wu H, Man X, et al. miR-301a-mediated crosstalk between the Hedgehog and HIPPO/YAP signaling pathways promotes pancreatic cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2025;26(1):2457761.

doi pubmed - Kolluru V, Chandrasekaran B, Tyagi A, Dervishi A, Ankem M, Yan X, Maiying K, et al. miR-301a expression: Diagnostic and prognostic marker for prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2018;36(11):503 e509-503 e515.

doi pubmed - Peng LN, Shi WT, Feng HR, Wei CY, Yin QN. Effect of miR-301a/PTEN pathway on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer. Innate Immun. 2019;25(4):217-223.

doi pubmed - Zheng JZ, Huang YN, Yao L, Liu YR, Liu S, Hu X, Liu ZB, et al. Elevated miR-301a expression indicates a poor prognosis for breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2225.

doi pubmed - https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid/.

- Kruger J, Rehmsmeier M. RNAhybrid: microRNA target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W451-454.

doi pubmed - Schmittgen TD, Lee EJ, Jiang J, Sarkar A, Yang L, Elton TS, Chen C. Real-time PCR quantification of precursor and mature microRNA. Methods. 2008;44(1):31-38.

doi pubmed - Salmena L, Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell. 2008;133(3):403-414.

doi pubmed - Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654-659.

doi pubmed - Chen X, Liang H, Zhang J, Zen K, Zhang CY. Horizontal transfer of microRNAs: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Protein Cell. 2012;3(1):28-37.

doi pubmed - Hoxhaj G, Manning BD. The PI3K-AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(2):74-88.

doi pubmed - Park JH, Lee JY, Shin DH, Jang KS, Kim HJ, Kong G. Loss of Mel-18 induces tumor angiogenesis through enhancing the activity and expression of HIF-1alpha mediated by the PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway. Oncogene. 2011;30(45):4578-4589.

doi pubmed - Derakhshan F, Reis-Filho JS. Pathogenesis of triple-negative breast cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2022;17:181-204.

doi pubmed - Varghese E, Samuel SM, Abotaleb M, Cheema S, Mamtani R, Busselberg D. The "Yin and Yang" of natural compounds in anticancer therapy of triple-negative breast cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(10).

doi pubmed - Yin J, Chen D, Luo K, Lu M, Gu Y, Zeng S, Chen X, et al. Cip2a/miR-301a feedback loop promotes cell proliferation and invasion of triple-negative breast cancer. J Cancer. 2019;10(24):5964-5974.

doi pubmed - Pore N, Liu S, Haas-Kogan DA, O'Rourke DM, Maity A. PTEN mutation and epidermal growth factor receptor activation regulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) mRNA expression in human glioblastoma cells by transactivating the proximal VEGF promoter. Cancer Res. 2003;63(1):236-241.

pubmed - Kogure T, Lin WL, Yan IK, Braconi C, Patel T. Intercellular nanovesicle-mediated microRNA transfer: a mechanism of environmental modulation of hepatocellular cancer cell growth. Hepatology. 2011;54(4):1237-1248.

doi pubmed - Lu J, Liu QH, Wang F, Tan JJ, Deng YQ, Peng XH, Liu X, et al. Exosomal miR-9 inhibits angiogenesis by targeting MDK and regulating PDK/AKT pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):147.

doi pubmed - Wang J, Wang C, Li Y, Li M, Zhu T, Shen Z, Wang H, et al. Potential of peptide-engineered exosomes with overexpressed miR-92b-3p in anti-angiogenic therapy of ovarian cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11(5):e425.

doi pubmed - Yu H, Li H, Qian H, Jiao X, Zhu X, Jiang X, Dai G, et al. Upregulation of miR-301a correlates with poor prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31(11):283.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.