| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://wjon.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 17, Number 1, February 2026, pages 34-51

Clinical Significance and Potential Molecular Mechanisms of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 in Colorectal Cancer

Da Tong Zenga, g, Li Yangb, g, Jia Ying Wenc, Ke Jun Wud, Guo Qiang Chend, Zong Yu Lid, Jing Wen Lingd, e, Bei Bei Huangd, Ying Yi Xied, Yi Yu Dongd, Ye Ying Fangf, Dan Ming Weid, Gang Chend, Lin Shib, h , Wei Jian Huanga, h

aDepartment of Pathology, Redcross Hospital of Yulin City, Yulin, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 537000, China

bDepartment of Pathology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 530000, China

cDepartment of Radiotherapy, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 530000, China

dDepartment of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 530021, China

eDepartment of Medical Information Engineering, School of Information and Management, Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 530199, China

fDepartment of Radiotherapy, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 530021, China

gThese authors contributed equally to this article.

hCorresponding Author: Lin Shi, Department of Pathology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 530000, China; Wei Jian Huang, Department of Pathology, Redcross Hospital of Yulin City, Yulin, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 537000, China

Manuscript submitted August 5, 2025, accepted October 28, 2025, published online December 17, 2025

Short title: Upregulation of ACE2 in CRC

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon2650

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) exhibits tumor-suppressive potential in cancers, but its role in colorectal cancer (CRC) is unclear. The aim of the study was to investigate ACE2 expression, clinical significance, and immune microenvironment associations in CRC.

Methods: A multidimensional approach was taken using single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics to analyze ACE2 expression in CRC cells. High-throughput data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (2,275 CRC and 1,269 adjacent tissues) were used to assess mRNA levels. Immunohistochemistry was performed to examine ACE2 protein expression in 66 CRC and 75 adjacent tissues. Molecular testing assessed associations with Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog (NRAS), and B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) mutations. Immune infiltration was analyzed using single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA), focusing on 24 immune cell types, CD8+ T cells, and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) correlations.

Results: ACE2 was highly expressed in malignant cells and Ki-67-activated regions. mRNA and protein levels were upregulated in CRC (standardized mean difference (SMD) = 0.321, area under the curve (AUC) = 0.844). High ACE2 exhibited significant associations with nerve invasion, lower expression in mucinous adenocarcinomas, and NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K) mutations. ACE2 negatively showed an inverse correlation with CD8+ T-cell infiltration (r = -0.186, P < 0.001) and PD-L1 expression (r = -0.282, P = 0.022).

Conclusions: The upregulation of ACE2 is associated with nerve invasion, pathological type, and an immunosuppressive microenvironment with reduced CD8+ T-cell infiltration and PD-L1 expression.

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; Colorectal cancer; Immune microenvironment; Immunosuppressive; Nerve invasion; PD-L1; CD8; Mucinous adenocarcinoma; NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K) mutation

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Background

Cancer is garnering increased attention as a prominent cause of mortality [1-4]. In 2020, colorectal cancer (CRC) was responsible for over 1.9 million newly diagnosed cases and 935,000 deaths, representing approximately 1 in 10 cancer cases and fatalities and ranking third in incidence and second in mortality [5]. The global economic impact of cancer is staggering, with a projected financial burden of $25.2 trillion on the world economy from 2020 to 2050. Among various types of cancer, CRC stands out as the second-highest contributor to this cost [6]. Moreover, research on the pan-cancer burden and the socioeconomic development index (SDI) has shown that a higher SDI is often associated with an increased risk of CRC [7]. CRC is a multifaceted, intricate disease with a large number of factors contributing to its pathogenesis, including genetic mutations, abnormalities in signaling pathways, DNA methylation, epigenetic regulation, inflammatory response, and immune regulation [8-14]. These factors interact with one another to promote the occurrence and development of CRC. In patients with tumors, both protumor and antitumor factors are induced in the body, including increased neutrophil and platelet levels and decreased lymphocyte levels [15, 16]. A comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms is of paramount significance to elucidate the pathophysiological processes associated with CRC, facilitate the development of innovative therapeutic strategies, and enable accurate prognostic assessments [17].

Oncology patients exhibit heightened susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and are at an elevated risk of experiencing critical events during the course of a novel coronavirus pneumonia pandemic, such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [18]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which serves as the primary receptor for host cell entry [19-21], has drawn significant attention in scientific circles. ACE2 is not only a monocarboxypeptidase but also a functional receptor located on the cell surface [22]. It plays a pivotal role in regulating the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) by catalyzing the hydrolysis of angiotensin (Ang) II into Ang-(1-7), thereby inhibiting angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) activation and exerting vasoconstrictive, proinflammatory, and thrombotic effects. Additionally, Ang-(1-7) stimulates the release of nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2, and bradykinin through Mas receptors, leading to vasodilation, natriuresis, and attenuation of oxidative stress and inflammation [23, 24].

ACE2 exhibits significant expressions not only in the heart, kidney, and respiratory tract but also in the colon [25-27]. In the context of cancer, ACE2 shows an inverse correlation with the activation of several oncogenic pathways, such as cell cycle, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), Wnt, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), thereby impeding tumor proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [28-30]. Furthermore, ACE2 is positively associated with antitumor immune response and serves as a favorable prognostic indicator in diverse cancer types, implying a potential protective function of ACE2 in cancer progression [31]. Previous investigations have indicated the potential involvement of the RAS in the pathophysiology of CRC initiation and progression [32-34]. Moreover, it has been proposed that ACE2 and its associated factors contribute to the underlying mechanisms linking CRC and COVID-19 [35]. Notably, several studies have confirmed the heightened expression of the ACE2 protein in human CRC [36]. Nevertheless, the available literature on ACE2 expression and its clinical significance in CRC remains scarce, and the extant reports have limitations, including small sample sizes, an absence of validation using independent clinical samples, and a dearth of molecular mechanism investigations.

Aim

In this investigation, we postulate that elevated ACE2 expression is closely associated with colon cancer development. To explore the potential clinical significance and molecular mechanisms of ACE2 in CRC, we conduct in-house experiments encompassing immunohistochemistry (IHC), RNA sequencing data collection, genetic testing (B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF)-V600E/Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS)/neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog (NRAS)), and analysis of clinical parameters. Additionally, we seek to gain further insights into the relationship between ACE2 expression and the level of immune cell infiltration in colon cancer by assessing programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and CD8. These findings hold promise for advancing the clinical management of colon cancer and enhancing our understanding of its pathogenesis.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

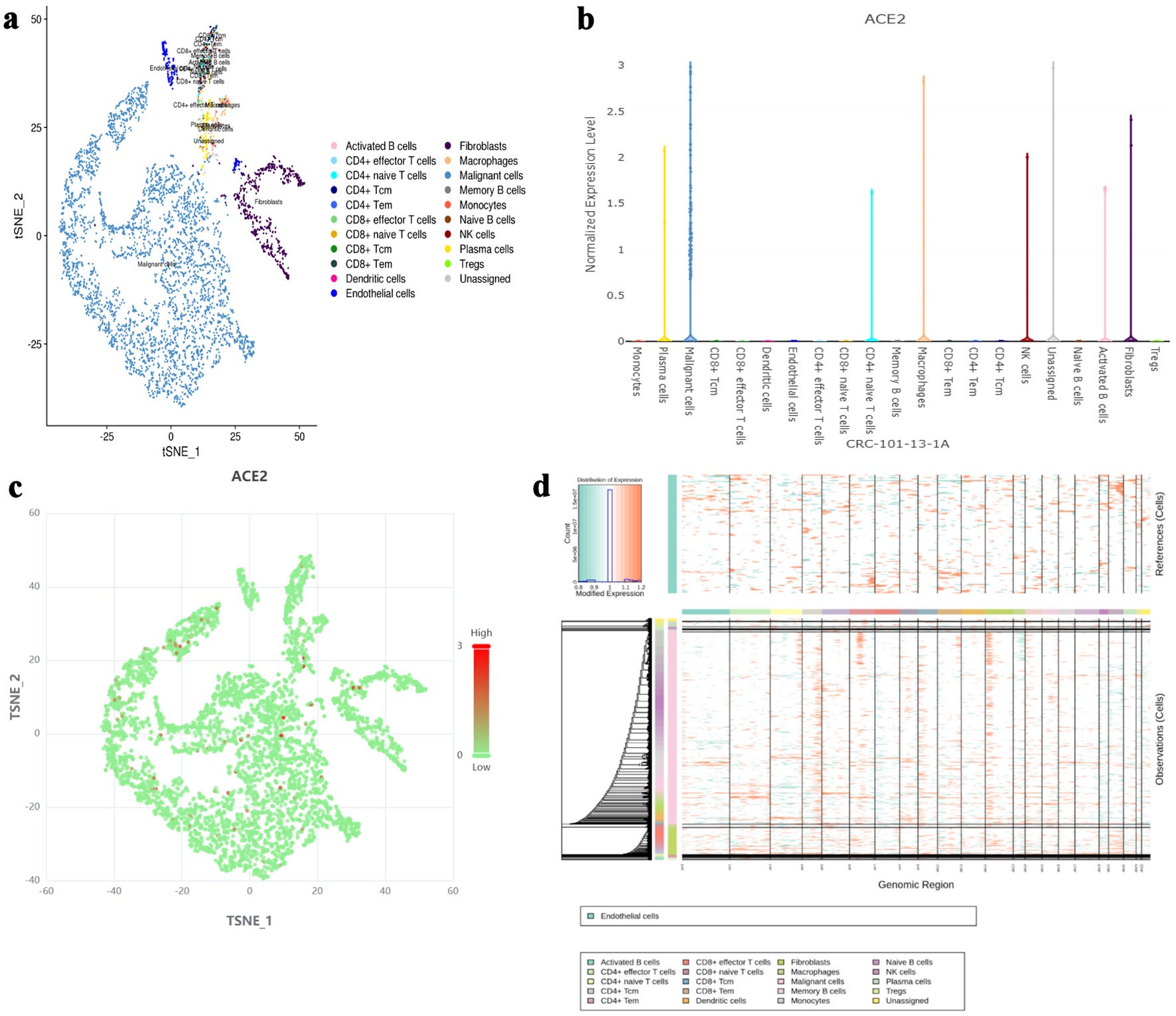

Single-cell RNA (scRNA) sequencing analysis of ACE2 in CRC cells

For scRNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis of ACE2, we used the cancer-related GSE201348 scRNA dataset, publicly released on April 28, 2022, and accessible through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. First, data preprocessing and filtering were performed using the Seurat package. Genes expressed in fewer than three cells and cells expressing fewer than 50 genes were removed. Next, during the quality control process, cells expressing more than 500 genes and with mitochondrial content below 25% were retained. After data normalization, principal component analysis was performed for dimensionality reduction, and the first 20 principal components were selected for clustering analysis. Subsequently, the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) algorithm was used for secondary dimensionality reduction. Additionally, the InferCNV package was employed to identify malignant tumors.

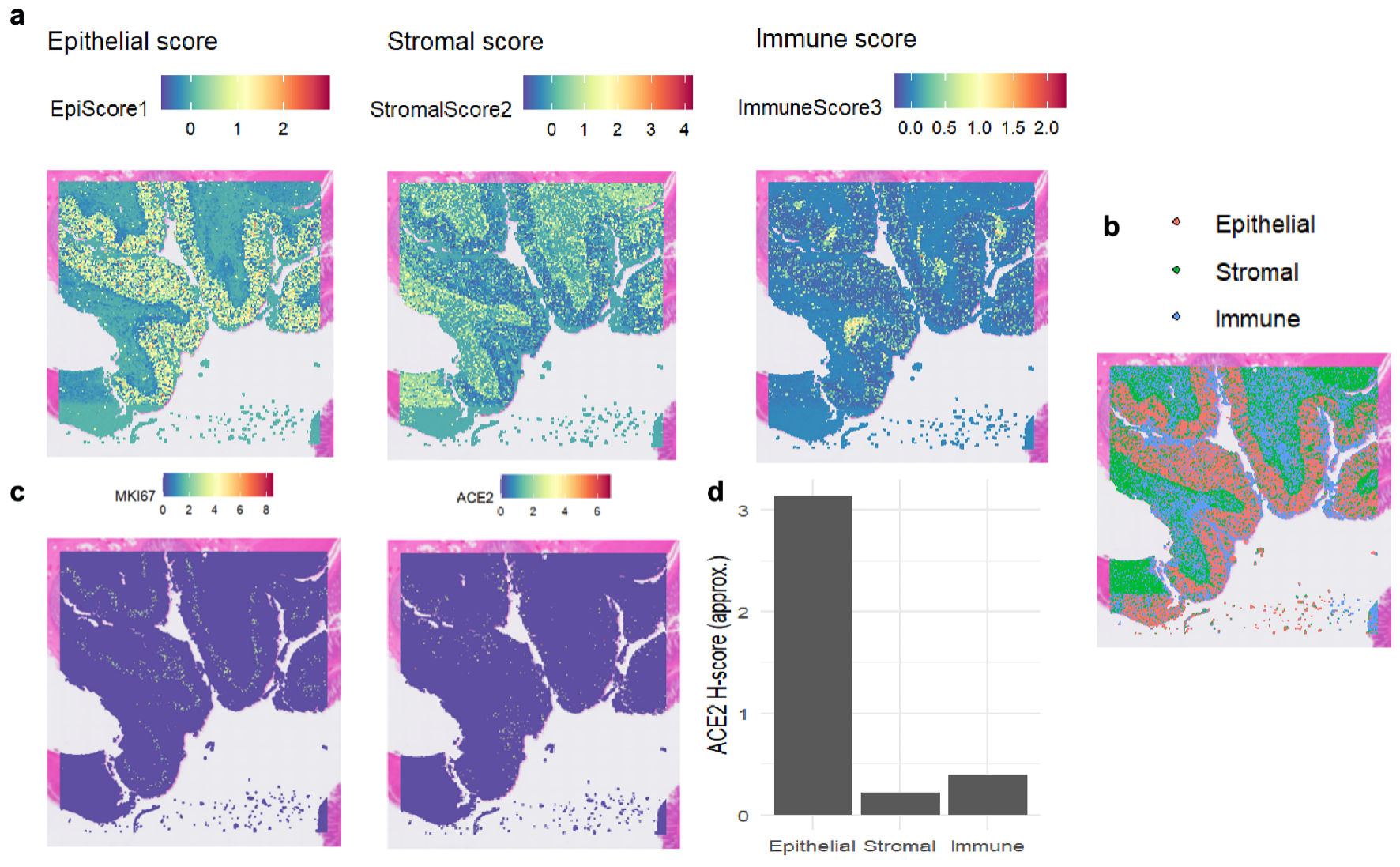

Spatial transcriptome analysis of ACE2 in CRC cells

Spatial transcriptomic data were acquired using the 10x Genomics Visium platform, followed by normalization and preprocessing using Seurat v5. To elucidate the spatial distribution of distinct cell types within tissue, deconvolution analysis was applied to map single-cell transcriptomic reference data onto spatial transcriptomic data. This allowed for the estimation of the relative compositional proportions of epithelial, stromal, and immune cells at each spatial spot. Based on the deconvolution results, three cell-type-specific scores (epithelial score, stromal score, and immune score) were calculated. The cell type corresponding to the highest score was defined as the dominant cell type for that spatial spot. Subsequently, spatial distribution maps of these three scores were visualized on the spatial coordinates of tissue sections to reflect the histological localization of different cell populations. Additionally, the spatial expression profiles of key genes - MKI67 (a cell proliferation marker) and ACE2 (a receptor gene) - were analyzed. Approximate IHC H-scores were computed based on the distribution of expression levels. Four intensity grades (0, 1+, 2+, and 3+) were defined using expression quantiles, and H-scores for each cell-type-enriched region were calculated using the formula H = 1 × %1 + 2 × %2 + 3 × %3. These scores were used to compare ACE2 expression among distinct cell types.

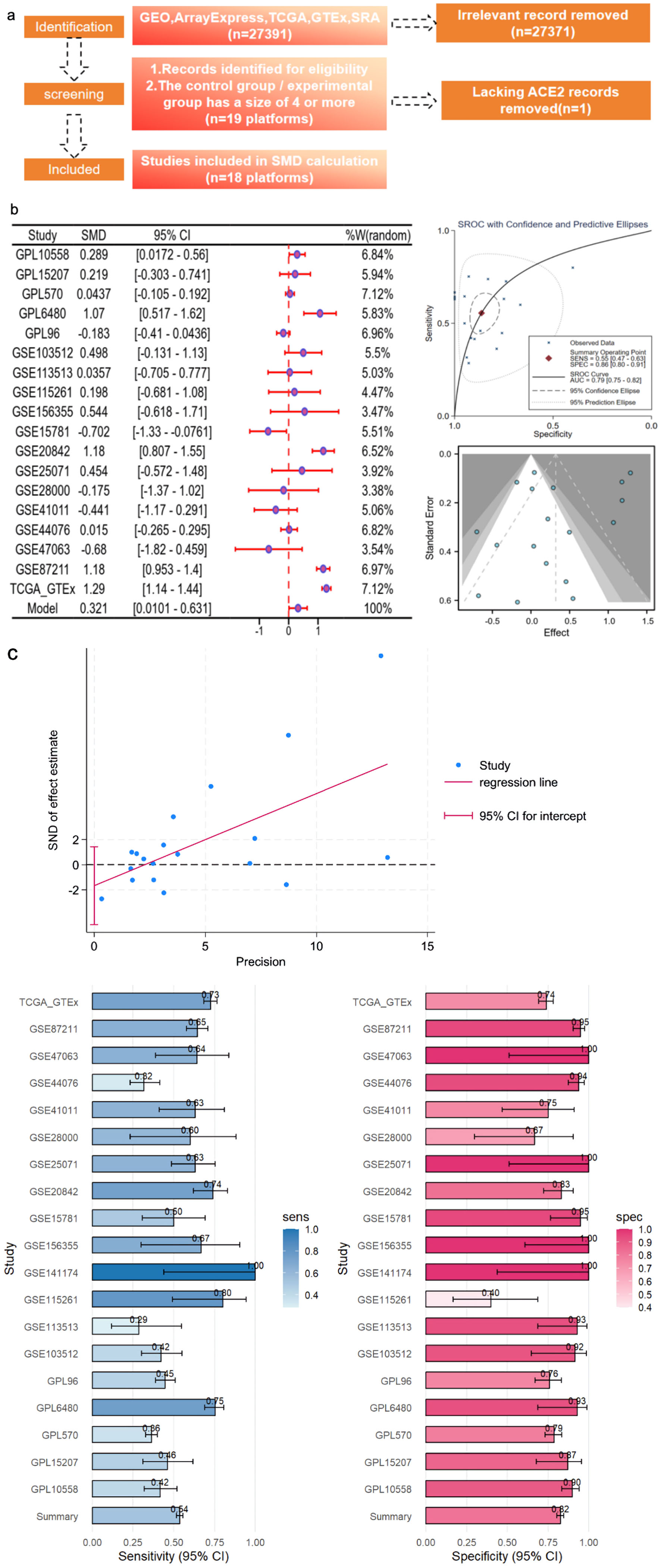

Collection and processing of datasets

To ensure comprehensive data retrieval, high-throughput datasets were systematically queried against multiple databases, including the Gene Expression Omnibus, ArrayExpress [37], the Sequence Read Archive, Oncomine, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), and PubMed. Relevant mRNA microarray data were extracted, encompassing a comprehensive cohort of 2,275 CRC samples and 1,269 adjacent samples. The search strategies employed were based on the keywords “colorectal cancer” or “CRC” and “mRNA” or “gene.” In the case of mRNA microarrays, the inclusion criteria were defined as follows: 1) the presence of diagnosed CRC tissue in the samples; 2) each chip containing both CRC and corresponding normal tissues; 3) the availability of ACE2 expression data; and 4) the samples originating from Homo sapiens. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) an absence of ACE2 expression data; 2) a lack of normal controls; and 3) samples originating from non-Homo sapiens species. To augment the normal samples and enhance the dataset, the Genotype Expression (GTEx) project was used in combination with the TCGA. The detailed datasets and sample sizes are shown in Table 1.

Click to view | Table 1. The Datasets Used in the Research |

The gene expression values from the publicly available datasets underwent a log2(X + 1) transformation, where X represents the raw data of gene expression. Microarrays from the Gene Expression Omnibus database with the same platform were merged to facilitate subsequent analysis. To mitigate batch effects within the combined microarrays, we employed the surrogate variable analysis package in R (v. 4.0.2). Subsequently, ACE2 expression was quantified based on the aforementioned datasets.

An integrated diagnostic performance analysis of 19 studies showed that the pooled sensitivity was moderate, and the pooled specificity was moderate to high, with all studies consistent with the overall estimate. Deeks’/Egger’s funnel plots did not indicate significant small-study effects or publication bias. After sensitivity analyses using multiple methods, there were no substantial changes in the pooled results, confirming that the pooled estimate of diagnostic accuracy in this study was robust.

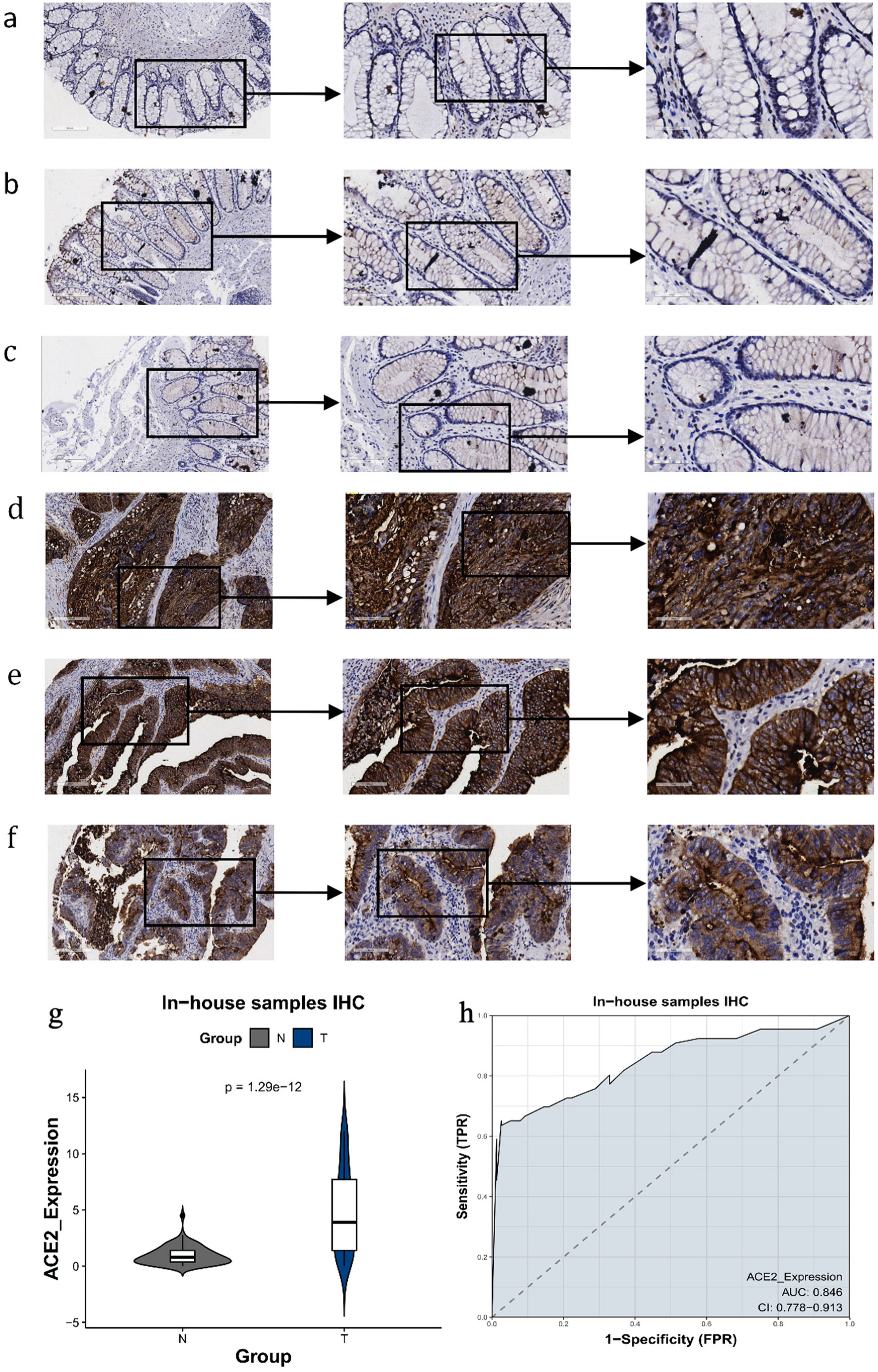

Expression of the ACE2 protein in CRC

All experiments were performed according to applicable rules. IHC was employed to assess the protein expression of ACE2. A total of 66 CRC and 76 adjacent colon tissue samples were procured for this study from Shanghai Outdo Biotech Company, China (catalog no. HColA160Bc01). The formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded samples underwent a dehydration procedure, followed by inhibition of endogenous peroxidase activity and antigen retrieval. The two-step IHC technique was employed [38]. An anti-ACE2 antibody (rabbit polyclonal to ACE2, Abcam) was employed as the first antibody in the experimental group, and phosphate-buffered saline was used as a comparison, replacing the initial antibody. Both were incubated overnight at 37 °C, after which the second antibody was added to the samples at 25 °C and incubated for 0.5 h. After hematoxylin staining, two pathologists independently evaluated the staining intensity and the percentage of stained positive cells. The score of ACE2 protein expression was the product of the staining strength score and the score of the percentage of positive stained cells, as previously reported [39].

Statistical analysis of ACE2 expression in CRC

The ACE2 protein’s differential expression in CRC tissues and non-CRC colorectal tissues was examined using Student’s t-test via IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, generated using GraphPad Prism 8 software, were used to evaluate ACE2’s ability to discriminate between CRC tissues and non-CRC colorectal tissues, with the area under the curve (AUC) serving as a measure of its accuracy. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze the enumeration data, specifically investigating the associations between ACE2 expression and various clinicopathological parameters, including sex, age, tumor node metastasis stage, pathological stage, pathological type, tumor size, tumor number, nerve invasion, and vascular invasion. These parameters were obtained from IHC samples. Statistical significance was assessed at a threshold of P < 0.05.

To enhance confidence in the findings, we amalgamated high-throughput datasets to augment the sample size. The standardized mean difference (SMD) and summary ROC (SROC) curves were employed as the primary indicators to quantify ACE2 expression and discriminative ability in CRC. Calculations were performed using Stata 15.0 software. The SMD and 95% confidence interval (CI) were employed to compare ACE2 expression between CRC and non-CRC colorectal tissues. The heterogeneity of the pooled-analysis results was evaluated using the I2 statistic. A P value of less than 0.05 or an I2 exceeding 50% indicated significant heterogeneity, whereupon a random-effects model was employed. Conversely, in cases in which the P value was greater than 0.05 or the I2 less than 50%, no significant heterogeneity was detected, allowing for the use of a fixed-effects model. Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s test. SROC curves were generated using Stata software.

Molecular testing and statistical analysis of ACE2-associated genes

To identify genes closely associated with ACE2 expression, molecular testing of KRAS, NRAS (G12C/D/S), NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K), and BRAF-V600E was conducted on in-house samples. The relationship between ACE2 expression and KRAS, NRAS (G12C/D/S), NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K), and BRAF-V600E was assessed using Student’s t-test and Pearson correlation analysis on SPSS 26.

Correlation and immune infiltration analysis of ACE2 in CRC

The study analyzed the correlation between the primary variable, ACE2 (ENSG00000130234.12), and the immune infiltration matrix data. Correlation analysis was performed using the Spearman method, and the results were visualized with a lollipop plot using the ggplot2 package in R. Immune infiltration was assessed using the ssGSEA algorithm from the Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) package (version 1.46.0), which calculated the infiltration levels of 24 immune cell types based on marker genes provided by Immunity. The 24 immune cell types included activated dendritic cells (aDCs), B cells, CD8 T cells, cytotoxic cells, dendritic cells (DCs), eosinophils, immature dendritic cells (iDCs), macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, natural killer (NK) CD56 bright cells, NK CD56 dim cells, NK cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), T cells, T helper cells, T central memory (Tcm) cells, T effector memory (Tem) cells, T follicular helper (TFH) cells, T gamma delta (Tgd) cells, Th1 cells, Th17 cells, Th2 cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Data were obtained from the TCGA database, specifically from the TCGA-COAD (CRC) project, where RNA-seq data processed via the Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) pipeline were downloaded and converted to transcripts per million (TPM) format, along with clinical data. Normal samples were excluded during data filtering, and the data were processed using a log2(value + 1) transformation.

Expression of CD8 and PD-L1 in CRC

To identify immune-related molecules closely associated with the expression of ACE2, an IHC test targeting CD8 and PD-L1 was conducted on the in-house samples. The relationship between ACE2 expression and both CD8 and PD-L1 was examined using Student’s t-test and Pearson correlation analysis using SPSS 26.

Ethical considerations

This research adhered to the fundamental medical ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Redcross Hospital of Yulin City (contract no. Z-K20221823).

| Results | ▴Top |

Expression of ACE2 in single-cell and spatial transcriptomics

Single-cell sequencing data indicated that ACE2 was highly expressed in malignant cells, with expression levels approaching 3, as shown in Figure 1a-c. InferCNV analysis confirmed the presence of diploid mutations in malignant cells, verifying their malignancy, as depicted in Figure 1d. The results of spatial deconvolution showed that three major cell regions could be clearly distinguished in the tissue sections: the epithelial regions, mainly distributed in the glands and the surface layer of the mucosa, exhibited the highest epithelial score; the stromal regions, located in the interstitial area of the glands, had a relatively high stromal score; and the immune regions, concentrated in the peripheral areas of the tissue or local infiltrative regions. Spatial gene expression analysis revealed that MKI67 was highly expressed in epithelial regions with active proliferation, while ACE2 was mainly concentrated in epithelial cell regions, and its expression was significantly reduced in stromal and immune regions. Further H-score analysis demonstrated that the average H-score of ACE2 in epithelial cells was approximately 3, which was much higher than that in stromal cells and immune cells (H-score < 0.5). This finding suggests that ACE2 expression has distinct cell-type specificity, being mainly restricted to epithelial cells, whereas only low-level background signals are observed in stromal and immune components, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The expression level of ACE2 protein in different cell types based on single-cell RNA sequencing. (a) t-SNE plot showing the distribution of various cell types (activated B cells, fibroblasts, CD4+ naive T cells, macrophages, CD4+ effector T cells, malignant cells, memory B cells, monocytes, naive B cells, plasma cells, Tregs, unassigned) in the dataset. (b) Bar chart representing the normalized expression level of ACE2 protein across different cell types. (c) t-SNE plot highlighting ACE2 expression levels, with red dots indicating higher expression and green dots indicating lower expression. (d) InferCNV analysis for malignancy assessment, with a color gradient indicating expression levels and malignancy likelihood. ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; t-SNE: t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding; Tregs: regulatory T cells; CRC: colorectal cancer; NK: natural killer. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. The expression levels of MKI67 and ACE2 proteins in colon tissue based on spatial transcriptomics. (a) Heat maps depicting regional scores of epithelial cells, stromal cells, and immune cells, illustrating the distribution of each component’s score. (b) Spatial distribution of epithelial cells, stromal cells, and immune cells, with different colors labeling the locations of the three cell components. (c) Heat maps showing the spatial distribution of MKI67 and ACE2 gene expression, where colors correspond to gene expression levels. (d) Bar chart of ACE2 H-scores in epithelial, stromal, and immune cells, comparing ACE2 expression levels across the three cell components. ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; MKI67: marker of proliferation Ki-67. |

Upregulation of ACE2 expression in CRC tissues

Multiple high-throughput datasets, comprising 2,275 CRC samples and 1,269 non-CRC colorectal samples, were used for the comprehensive analysis of ACE2 mRNA expression (Fig. 3a). A forest plot yielded an SMD of 0.321, indicating that ACE2 expression was significantly upregulated in CRC (Fig. 3b). The overall area under the SROC curve was 0.79 (95% CI: 0.75 - 0.82). The Begg’s test result indicated no publication bias (P > 0.05), and the funnel plot showed no heterogeneity (Fig. 3b). The integrated diagnostic efficacy of 19 studies showed a summary sensitivity of moderate level and a summary specificity of moderately high level (all studies in the forest plot largely overlapped with the overall estimate and were consistent in direction). The Deeks/Egger regression funnel plot showed no significant asymmetry, with the 95% CI of the intercept crossing zero, indicating no substantial small-study effects or publication bias. Sensitivity analyses were conducted, incorporating sequential leave-one-out exclusion of individual studies, application of continuity correction, and use of alternate estimation models. These analyses demonstrated no substantial changes in the direction or magnitude of pooled sensitivity and specificity, with overall significance remaining unaffected. Moreover, consistent conclusions were maintained even after removing outlier studies characterized by extreme sensitivity or specificity values. In summary, the sensitivity analysis confirmed that the combined estimate of diagnostic accuracy in this study is robust (Fig. 3c).

Click for large image | Figure 3. CRC ACE2 mRNA samples were obtained from a multicenter high-throughput dataset, including 2,275 CRC samples and 1,269 non-CRC colorectal samples. (a) Flow plot. (b) ACE2 expression in bulk mRNA data. (c) Egger’s test: detection of publication bias (P = 0.027); sensitivity and specificity analysis. ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; AUC: area under the curve; CRC: colorectal cancer; GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; SMD: standardized mean difference; SROC: summary receiver operating characteristic; CI: confidence interval; GTEx: Genotype Expression. |

Compared to the non-CRC colorectal samples, the expression of the ACE2 protein in the CRC samples was significantly increased (Fig. 4). Positive staining signals for ACE2 were localized predominantly in the cytoplasm of CRC cells, rather than in paracancerous colonic mucosal cells. The AUC was 0.844, indicating a substantial discriminatory capacity of ACE2 expression in distinguishing between CRC samples and non-CRC colorectal samples.

Click for large image | Figure 4. The expression level of ACE2 protein in CRC and peritumor colon tissues based on IHC. (a-c) Representative images of ACE2 protein expression in peritumor colon tissues. (d-f) Representative images of ACE2 protein expression in CRC tissues. In panels (a-f), the magnifications of the three images of each panel are 100, 200, and 400 respectively. (g) ACE2 protein expression (P = 1.29 × 10-12). (h) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve with area under the curve (AUC) of ACE2 protein expression in CRC tissues. ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; CRC: colorectal cancer; IHC: immunohistochemistry; TPR: true positive rate; FPR: false positive rate. |

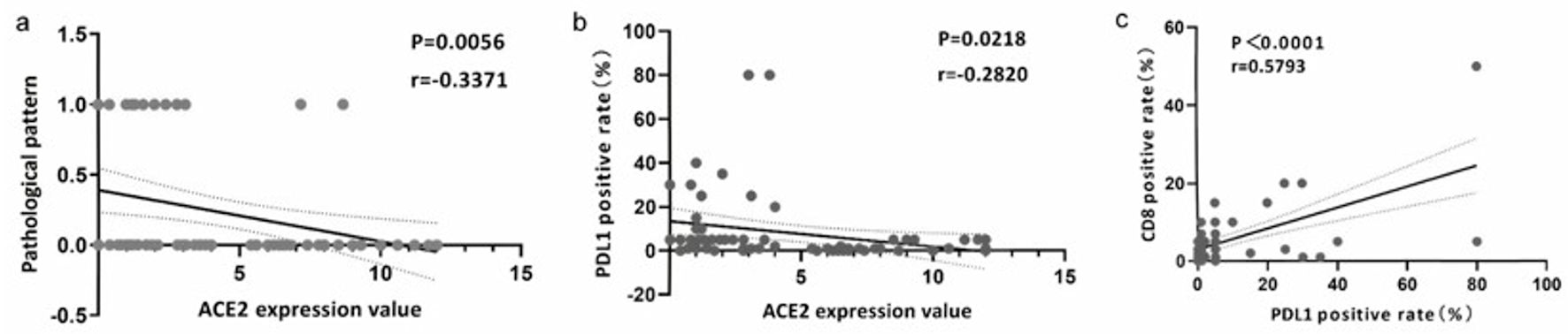

Other clinical value of ACE2 in CRC

In the IHC analysis using internal samples (Table 2), we observed that CRC cases with nerve invasion exhibited elevated ACE2 protein expression levels, whereas mucinous adenocarcinomas generally displayed low or negligible ACE2 protein expression. Notably, there was a significant difference but no correlation between ACE2 expression values and nerve invasion. However, we observed a negative correlation between ACE2 expression values and pathologic types (r = -0.3371, P = 0.0056) (Fig. 5a). The remaining clinical parameters did not demonstrate statistical significance.

Click to view | Table 2. The Relationships of ACE2 Expression With the Clinicopathologic Parameters by Interpretation of the Immunohistochemistry |

Click for large image | Figure 5. The expression of ACE2 was associated with CD8 and PD-L1. (a) Correlation analysis of ACE2 expression value and pathological pattern. (b) Correlation analysis of ACE2 expression value and PD-L1 positive rate (%). (c) Correlation analysis of PD-L1 and CD8 positive rate (%). ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; PD-L1: programmed death ligand 1. |

Relationship between ACE2 expression and NRAS mutation

In IHC and genetic test analyses conducted on internal samples (Table 2), we observed a significant difference in ACE2 expression values compared to the NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K) mutation, although no correlation was found. However, the remaining mutations did not exhibit statistical significance, including BRAF (V600E), KRAS, and NRAS (G12C/D/S).

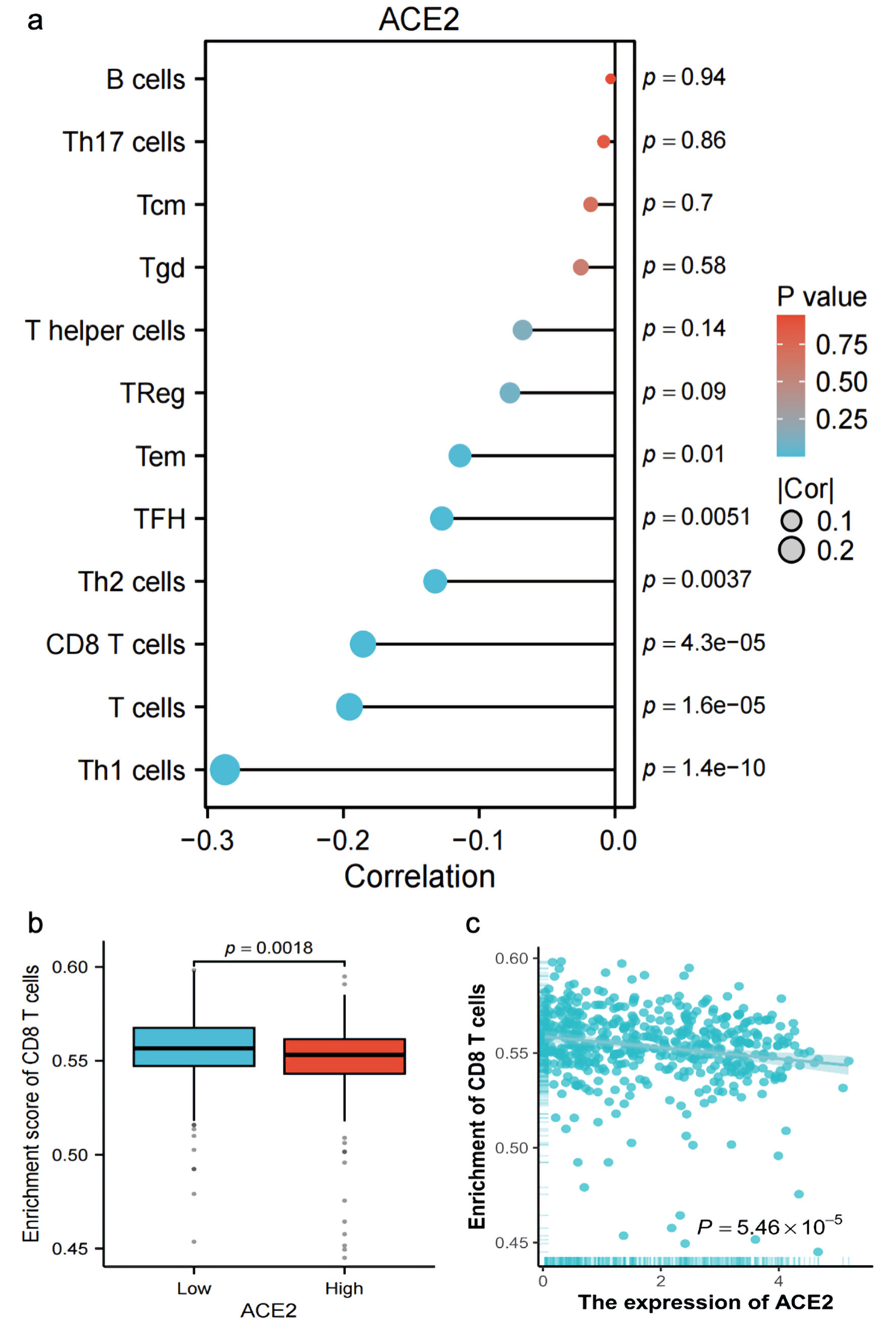

Correlation of ACE2 expression with T-cell subtypes

The expression of ACE2 exhibited a negative correlation with numerous T-cell subtypes, with correlation coefficients less than 0.1 and P values equal to 1.4 × 10-10, indicating a statistically significant inverse relationship (Fig. 6a). Additionally, a negative Spearman correlation (r = -0.186, P = 5.46 × 10-5) between ACE2 expression (log2(TPM + 1)) and CD8 T-cell enrichment was observed (Fig. 6b, c), suggesting that higher ACE2 expression was associated with reduced CD8 T-cell infiltration across the analyzed samples.

Click for large image | Figure 6. Correlation and enrichment analysis of ACE2 expression with immune cell types and CD8 T cell activity. (a) Bar plot showing the correlation (R) and P value of ACE2 expression with various immune cell types (Th1 cells, T cells, CD8 T cells, Th2 cells, TFH, Tem, Treg, T helper cells, Tgd, Tcm, Th17 cells, B cells), with color indicating P value significance. (b) Box plot comparing the enrichment score of CD8 T cells between low and high ACE2 expression groups (P = 0.0018). (c) Scatter plot showing the relationship between ACE2 expression (Log2(TPM + 1)) and CD8 T-cell enrichment score, with Spearman correlation (R = -0.186, P = 5.46 × 10-5). ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; Tcm: T central memory; Tem: T effector memory; TFH: T follicular helper; Tgd: T gamma delta; Th1: T helper 1; Th17: T helper 17; Th2: T helper 2; Tregs: regulatory T cells; TPM: transcripts per million. |

Association of ACE2 expression with CD8 and PD-L1

In the IHC analysis based on internal samples, a negative correlation was observed between ACE2 expression levels and PD-L1 positivity (r = -0.282, P = 0.022) (Fig. 5b). Conversely, a positive correlation was found between CD8 positivity and PD-L1 positivity (r = 0.5793, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5c).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Growing evidence links RAS to tumor growth and development [40-43]. ACE2, a key RAS regulator, has been well studied in COVID-19, but its role in CRC is unclear. This study analyzed 3,101 samples via multiple statistical methods and found significantly elevated ACE2 mRNA and protein levels in CRC. ACE2 protein expression in CRC patients correlated with tumor pathological type and PD-L1 expression and differed significantly in cases with neural invasion or NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K). These findings highlight ACE2’s high expression in CRC and its potential clinical significance and contribute to a deeper understanding of CRC’s molecular mechanisms.

Numerous studies have shown variable ACE2 expressions across tumor types. For example, it is downregulated in hepatocellular [38], breast [44], non-small cell lung [45], pancreatic ductal [46], and gallbladder cancers [47], but upregulated in endometrial and renal papillary cell carcinomas [48]. Previous CRC studies identified increased ACE2 [36, 49] but had limitations, such as small sample sizes (n < 500), limited data, or a lack of comprehensive multilevel analyses; some studies found no significant ACE2 protein differences. To address these gaps, our study used 66 in-house CRC samples, 76 non-CRC colorectal samples, and 2,960 multisource samples. We confirmed significant ACE2 upregulation in CRC (mRNA and protein levels). Importantly, ACE2 expression distinguished CRC from non-CRC samples - an unreported finding - and correlated with CRC tumor type.

Our study also found that colonic mucinous adenocarcinomas often showed low or no ACE2 expression. As a distinct subtype of CRC with specific molecular features [50, 51], this carcinoma progresses faster and is often diagnosed at an advanced stage compared to tubular adenocarcinoma [52]. Numerous studies have found that high Ang-(1-7) expression inhibits tumor proliferation, invasion, and migration in cancers such as nasopharyngeal [53], prostate [54], and lung cancer [55]. ACE2 has also been shown to inhibit tumor cell growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis in laryngeal, lung, gallbladder, and pancreatic cancers, as well as osteosarcoma [56]. Thus, low ACE2 expression is often linked to tumor progression. For example, downregulation of the ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas axis promotes breast cancer metastasis by activating the Store-Operated Calcium Entry (SOCE) and p21-activated kinase (PAK)/nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)/Snail1 pathways [57]. Notably, right-sided colonic mucinous adenocarcinoma correlates with extracellular matrix remodeling, EMT, and interleukin (IL)-17 signaling, while that on the left side may downregulate the ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas axis via differentially expressed proteins (reducing ACE2 and Ang-(1-7)), potentially promoting tumor progression and metastasis [58]. This axis partially explains the low ACE2 expression in the carcinoma.

In addition, this study observed a negative correlation between ACE2 expression values and PD-L1 positivity, despite the small values of the correlation coefficient, and subsequent analysis revealed a positive correlation between PD-L1 positivity and CD8 positivity. Given that PD-L1 is a key regulator of CD8+ T-cell function [59], this finding suggests that ACE2 may indirectly influence T-cell infiltration and activity. Evidence indicates that ACE2 is negatively correlated with angiogenesis and the TGF-β signaling pathway [60], both of which have been demonstrated to induce PD-L1 expression [61]. Concurrently, ACE2 was positively correlated with an abundance of M2 macrophages [60], which can directly suppress CD8+ T-cell function and proliferation through the secretion of factors such as IL-10 and TGF-β [59]. However, it must be clearly stated that these findings, based on correlative analyses and pathway inferences, cannot establish a direct causal relationship between ACE2 and PD-L1 expression or CD8+ T-cell infiltration. Chronic inflammation is widely recognized as a contributor to multiple stages of tumorigenesis and development, encompassing cell transformation, survival, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Notably, patients diagnosed with chronic inflammatory bowel disease face a substantially elevated risk of developing CRC [10, 62, 63]. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells play a pivotal role in eradicating intracellular infections and malignant cells [16, 64], exhibiting a remarkable capacity to selectively identify and eliminate cancer cells [62]. The overexpression of PD-L1 hampers the cytolytic activity of CD8+ T cells and diminishes T cell-mediated cytotoxicity, allowing the evasion of immune surveillance and substantially promoting tumorigenesis and tumor aggressiveness [63]. In the liver, chronic inflammation leads to the accumulation of immunoglobulin A (IgA)+ plasma cells that express PD-L1 and IL-10, resulting in the direct suppression of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and subsequent suppression of antitumor immunity [65]. Hence, the restoration of functional activity in CD8+ T cells within tumors is of paramount importance for the efficient eradication of tumor cells. Notably, natural killer group 2A (NKG2A)+ CD8+ T cells have been shown to be enriched in CRC, and obstructing NKG2A (or its ligands) enhances the cytotoxic response of these T cells toward CRC cells [66]. Furthermore, a positive correlation has been observed between an inflammatory immune microenvironment, elevated PD-L1 expression, and the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, and upregulation of ACE2 may serve as an indicative factor for increased responsiveness to immunotherapy [31]. Additional investigations have highlighted that bromelain and ficin possess not only anti-infection therapeutic applications but also dose-dependent inhibitory effects on the expression of ACE2. Consequently, this inhibition hinders the proliferation of CRC cells and induces their apoptotic pathways [67]. Moreover, emerging strategies in cancer therapy involve repurposing drugs as GLP-1-based therapies or targeting 20S proteasomes, as well as administering various natural compounds, such as hinokitiol, as prophylactic agents with immunomodulatory effects and positive impacts on cancer [68-70]. Hence, the involvement of ACE2 in CRC could potentially be associated with the immune response. Moreover, the integration of multiple strategies that target the immune system through ACE2, in conjunction with programmed cell death 1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 blockade-based therapy, may prove to be a highly significant combinatorial approach for future immunotherapy endeavors.

Furthermore, this investigation observed that CRC cases with neurological invasion generally exhibited elevated levels of ACE2 expression. However, due to the limited number of cases, the correlation between ACE2 expression and neurological invasion could not be conclusively established despite the observed differences. Interestingly, a separate study investigating COVID-19-related brainstem invasion reported that the gastrointestinal epithelium expresses ACE2 receptors to a greater extent than the lung [71]. It also revealed that novel coronaviruses can directly infect intestinal cells, efficiently replicate within them, and invade nerves, subsequently ascending to the central nervous system via entero-vagal afferents. These findings suggest an alternative pathophysiological mechanism [72]. The present study elucidated the mechanism underlying nerve invasion by enterocarcinoma cells with high ACE2 expression. However, further investigation is required to determine whether CRCs exhibiting elevated ACE2 expression are more prone to nerve invasion.

CRC exhibits a multistage pathogenesis, progressing from early developmental abnormalities to adenomatous polyps and eventually to invasive carcinoma. The emergence of carcinoma is contingent upon the progressive accumulation of alterations that promote tumor growth over time [73]. At the molecular level, the adenoma-carcinoma sequence pathway is characterized by an abundance of KRAS mutations and somatic copy number alterations. Conversely, the serrated lesion-carcinoma pathway is driven by promoter hypermethylation of genes subsequent to BRAF mutations [74]. The prevalence of NRAS mutations in CRC is lower than the prevalence of KRAS mutations. NRAS mutations typically arise at a later stage of tumor progression and are often observed either alone or in combination with a KRAS mutation during tumor recurrence [75]. These mutations result in KRAS wild-type tumors that exhibit resistance to anti-EGFR therapy [76]. Specifically, the NRAS (Q61K) mutation promotes anchor-dependent proliferation and tumorigenicity, resembling the characteristics driven by classical KRAS mutations. Conversely, NRAS (G12D) expression reduces proliferation and increases apoptosis [76]. To investigate the association between ACE2 and common gene mutations in CRC, we conducted genetic testing for BRAF (V600E), KRAS, NRAS (G12C/D/S), and NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K). The positive rates for these mutations were approximately 6%, 28%, 4%, and 5%, respectively, which aligns with the rates reported in the literature [77]. Regrettably, no statistically significant differences were observed except for a notable disparity between NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K) and ACE2 expression. Functional studies have demonstrated that NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K), by impairing GTP hydrolysis, constitutively activates the RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways [77, 78], subsequently upregulating c-Myc [79] and promoting cellular transformation and proliferation. It is noteworthy that the PI3K-AKT pathway has been reported to positively regulate ACE2 expression [36, 80], suggesting that NRAS (Q61R/L/H/K) may co-modulate ACE2 expression through this pathway, indicating a functional coupling at the signaling level. Furthermore, ACE2 mitigates inflammatory responses by degrading Ang II [81], potentially fostering a favorable immune microenvironment for NRAS-mutant tumors. Although the aforementioned mechanisms may exhibit variations across some tumor subtypes, the current evidence does not indicate significant differences in such signaling interactions among different subtypes of CRC. A previous study identified a significant reduction in ACE2 mRNA expression in KRAS-mutant tumors. Furthermore, ACE2 expression displays a negative correlation with KRAS, NRAS, Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (HRAS), and mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) but not with the expression levels of EGFR, BRAF, and ALK [82]. However, there remains a dearth of molecular mechanism studies exploring the relationship between ACE2 and BRAF (V600E), KRAS, and NRAS genes.

Strengths

Our study successfully validated the upregulation of ACE2 in CRC and investigated its potential clinical significance and underlying mechanisms. The overexpression of ACE2 holds promise as a potential biomarker for identifying CRC. Moreover, our findings suggest that ACE2 may be involved in CRC through antiangiogenic and immune response pathways, warranting further investigation. These findings contribute to our understanding of the role of ACE2 in CRC and provide a foundation for future research in this field.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, it lacks prognostic analysis, which would have provided valuable insights into the potential clinical implications of the findings. Additionally, the absence of in vitro functional experiments limits our ability to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and validate the observed associations. In the IHC cohort, there was insufficient statistical power when comparing different subgroups. These limitations highlight the need for further research to address these aspects and enhance our understanding of the subject matter.

Conclusions

ACE2 protein expression shows a close correlation with pathologic type and PD-L1 positivity among patients with CRC. The underlying molecular mechanisms of ACE2 may be related to antiangiogenesis and immune response.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of all public platforms that facilitated data collection and analysis in this study.

Financial Disclosure

This work was supported by the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Health Commission Scientific Research Project (No. Z-K20221823 and No. Z20210442); the Promoting Project of Basic Capacity for Young and Middle-aged University Teachers in Guangxi (No. 2025KY0164); and the Youth Science Foundation of Guangxi Medical University (No. GXMUYSF202423).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Author Contributions

Da Tong Zeng and Li Yang contributed equally to this work as co-first authors; they conducted data collection, performed immunohistochemical staining analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript. Lin Shi and Wei Jian Huang contributed equally to this work as co-corresponding authors; they provided guidance on experimental design, statistical analysis, and manuscript revision. Ke Jun Wu, Guo Qiang Chen and Jing Wen Ling performed tissue sample collection, clinical data analysis, and assisted with manuscript preparation. Bei Bei Huang conducted computational analysis and assisted with data visualization. Zong Yu Li, Ying Yi Xie, Yi Yu Dong , and Ye Ying Fang analyzed public high-throughput data, and contributed to data interpretation and preparation for the corresponding texts. Jia Ying Wen, Dan Ming Wei and Lin Shi assisted with patient recruitment, sample handling, and clinical data collection. Lin Shi also provided technical support and supervised experimental procedures. Gang Chen conceived and designed the study, supervised all experiments and data analysis, and finalized the manuscript. Wei Jian Huang provided clinical guidance, assisted with result interpretation, and critically corrected the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; CRC: colorectal cancer; GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; IHC: immunohistochemistry; KRAS: Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; NRAS: neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog; BRAF: B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase; ssGSEA: single-sample gene set enrichment analysis; PD-L1: programmed death ligand 1; AUC: area under the curve; SMD: standardized mean difference; ROC: receiver operating characteristic; SROC: summary receiver operating characteristic; CI: confidence interval; RAS: renin-angiotensin system; Ang II: angiotensin II; Ang-(1-7): angiotensin 1-7; AT1R: angiotensin II type 1 receptor; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; GTEx: Genotype Expression; scRNA-seq: single-cell RNA sequencing; UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection; SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; TCGA-COAD: The Cancer Genome Atlas-Colorectal Adenocarcinoma; RNA-seq: RNA sequencing; TPM: transcripts per million; aDC: activated dendritic cells; iDC: immature dendritic cells; pDC: plasmacytoid dendritic cells; Tcm: T central memory; Tem: T effector memory; TFH: T follicular helper; Tgd: T gamma delta; Th1: T helper 1; Th17: T helper 17; Th2: T helper 2; Tregs: regulatory T cells; NK: natural killer; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; ALK: anaplastic lymphoma kinase; HRAS: Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; MET: mesenchymal-epithelial transition; IL-17: interleukin-17; IgA: immunoglobulin A; IL-10: interleukin-10; NKG2A: natural killer group 2A; mRNA: messenger ribonucleic acid; STAR: Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference; GSVA: Gene Set Variation Analysis; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-beta; ArrayExpress: ArrayExpress database; SOCE: Store-Operated Calcium Entry; PAK: p21-activated kinase; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; t-SNE: t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding; MKI67: marker of proliferation Ki-67; SD: standard deviation; P (t): P value from t-test; t/F: t-statistic/F-statistic

| References | ▴Top |

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, Soerjomataram I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021;127(16):3029-3030.

doi pubmed - Xiaoyang X, Chunhui Z, Xiaolan Y, Dong Z. Effect of different types of aerobic exercises on cancer-related fatigue among colorectal cancer patients: a meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer. 2025;25(1):1145.

doi pubmed - Vidanapathirana G, Islam MS, Gamage S, Lam AK, Gopalan V. The role of iron chelation therapy in colorectal cancer: a systematic review on its mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Cancer Med. 2025;14(13):e71019.

doi pubmed - He Y, Wang X, Zhou M, Li L, Han T, He J, Mai W, et al. Global, regional and national burden of colon and rectum cancer: a systematic analysis of prevalence, incidence, deaths and DALYs from 1990 to 2021 using data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 with projections to 2036. BMJ Open. 2025;15(10):e100042.

doi pubmed - Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249.

doi pubmed - Chen S, Cao Z, Prettner K, Kuhn M, Yang J, Jiao L, Wang Z, et al. Estimates and Projections of the Global Economic Cost of 29 Cancers in 204 Countries and Territories From 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(4):465-472.

doi pubmed - Ma Z, Zou S, Liu R, Li S, Li Z. Socioeconomic development index (SDI) gradients and high BMI-Driven pan-cancer burden: a global burden of disease study on mortality, disability, and health inequities (2015-2021). BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):3295.

doi pubmed - Kok SY, Nakayama M, Morita A, Oshima H, Oshima M. Genetic and nongenetic mechanisms for colorectal cancer evolution. Cancer Sci. 2023;114(9):3478-3486.

doi pubmed - Malki A, ElRuz RA, Gupta I, Allouch A, Vranic S, Al Moustafa AE. Molecular mechanisms of colon cancer progression and metastasis: recent insights and advancements. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):130.

doi pubmed - Schmitt M, Greten FR. The inflammatory pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(10):653-667.

doi pubmed - Sedlak JC, Yilmaz OH, Roper J. Metabolism and colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2023;18:467-492.

doi pubmed - Zhang L, Zhang F, Liang H, Qin X, Mo Y, Chen S, Xie J, et al. Hippo/YAP signaling pathway in colorectal cancer: regulatory mechanisms and potential drug exploration. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1545952.

doi pubmed - Abdelgawwad El-Sehrawy AAM, Al-Dulaimi AA, Alkhathami AG, S RJ, Panigrahi R, Pargaien A, Singh U, et al. NRF2 as a ferroptosis gatekeeper in colorectal cancer: implications for therapy. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2025.

doi pubmed - Janeeh AS, Bajbouj K, Rah B, Abu-Gharbieh E, Hamad M. Interplay between tumor cells and immune cells of the colorectal cancer tumor microenvironment: Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1587950.

doi pubmed - Hammad R, Eldosoky MA, Elmadbouly AA, Aglan RB, AbdelHamid SG, Zaky S, Ali E, et al. Monocytes subsets altered distribution and dysregulated plasma hsa-miR-21-5p and hsa-miR-155-5p in HCV-linked liver cirrhosis progression to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(17):15349-15364.

doi pubmed - Hammad R, Aglan RB, Mohammed SA, Awad EA, Elsaid MA, Bedair HM, Khirala SK, et al. Cytotoxic T cell expression of leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1 (LAIR-1) in viral hepatitis C-mediated hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(20).

doi pubmed - Hamdy NM, Basalious EB, El-Sisi MG, Nasr M, Kabel AM, Nossier ES, Abadi AH. Advancements in current one-size-fits-all therapies compared to future treatment innovations for better improved chemotherapeutic outcomes: a step-toward personalized medicine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024;40(11):1943-1961.

doi pubmed - Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, Li C, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335-337.

doi pubmed - Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270-273.

doi pubmed - Bourgonje AR, Abdulle AE, Timens W, Hillebrands JL, Navis GJ, Gordijn SJ, Bolling MC, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS-CoV-2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Pathol. 2020;251(3):228-248.

doi pubmed - Rizopoulos T, Assimakopoulou M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression in human tumors: Implications for prognosis and therapy (Review). Oncol Rep. 2025;54(3).

doi pubmed - Beyerstedt S, Casaro EB, Rangel EB. COVID-19: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and tissue susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40(5):905-919.

doi pubmed - Cohen JB, Hanff TC, Bress AP, South AM. Relationship between ACE2 and other components of the renin-angiotensin system. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22(7):44.

doi pubmed - South AM, Shaltout HA, Washburn LK, Hendricks AS, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Fetal programming and the angiotensin-(1-7) axis: a review of the experimental and clinical data. Clin Sci (Lond). 2019;133(1):55-74.

doi pubmed - Ni W, Yang X, Yang D, Bao J, Li R, Xiao Y, Hou C, et al. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):422.

doi pubmed - Guo M, Tao W, Flavell RA, Zhu S. Potential intestinal infection and faecal-oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(4):269-283.

doi pubmed - Khalil BM, Shahin MH, Solayman MH, Langaee T, Schaalan MF, Gong Y, Hammad LN, et al. Genetic and nongenetic factors affecting clopidogrel response in the Egyptian population. Clin Transl Sci. 2016;9(1):23-28.

doi pubmed - Tang Y, Liu J, Liu L. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 suppresses pulmonary fibrosis associated with Wnt and TGF-beta1 signaling pathways. Discov Med. 2024;36(190):2274-2286.

doi pubmed - Wang S, Zhang X, Chong N, Chen D, Shu J, Wang R, Wang Q, et al. Dapagliflozin ameliorates high glucose-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via up-regulating ACE2 mediated by EZH2 in diabetic nephropathy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2025;48(10):2499-2509.

doi pubmed - Wang J, Xiang Y, Yang SX, Zhang HM, Li H, Zong QB, Li LW, et al. MIR99AHG inhibits EMT in pulmonary fibrosis via the miR-136-5p/USP4/ACE2 axis. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):426.

doi pubmed - Wang XS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 connects COVID-19 with cancer and cancer immunotherapy. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13(3):157-160.

doi pubmed - Mehranfard D, Perez G, Rodriguez A, Ladna JM, Neagra CT, Goldstein B, Carroll T, et al. Alterations in gene expression of renin-angiotensin system components and related proteins in colorectal cancer. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2021;2021:9987115.

doi pubmed - Zheng X, Liu G, Cui G, Cheng M, Zhang N, Hu S. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene deletion polymorphism is associated with lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer patients in a Chinese population. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:4926-4931.

doi pubmed - Makar GA, Holmes JH, Yang YX. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy and colorectal cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(2):djt374.

doi pubmed - Li S, Chen S, Zhu Q, Ben S, Gao F, Xin J, Du M, et al. The impact of ACE2 and co-factors on SARS-CoV-2 infection in colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(7):e967.

doi pubmed - Zhang S, Kapoor S, Tripathi C, Perez JT, Mohan N, Dashwood WM, Zhang K, et al. Targeting ACE2-BRD4 crosstalk in colorectal cancer and the deregulation of DNA repair and apoptosis. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2023;7(1):20.

doi pubmed - Athar A, Fullgrabe A, George N, Iqbal H, Huerta L, Ali A, Snow C, et al. ArrayExpress update - from bulk to single-cell expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D711-D715.

doi pubmed - Huang WJ, He WY, Li JD, He RQ, Huang ZG, Zhou XG, Li JJ, et al. Clinical significance and molecular mechanism of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues. Bioengineered. 2021;12(1):4054-4069.

doi pubmed - Zhang L, Luo B, Dang YW, He RQ, Chen G, Peng ZG, Feng ZB. The clinical significance of endothelin receptor type B in hepatocellular carcinoma and its potential molecular mechanism. Exp Mol Pathol. 2019;107:141-157.

doi pubmed - Kanehira T, Tani T, Takagi T, Nakano Y, Howard EF, Tamura M. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor gene deficiency attenuates susceptibility to tobacco-specific nitrosamine-induced lung tumorigenesis: involvement of transforming growth factor-beta-dependent cell growth attenuation. Cancer Res. 2005;65(17):7660-7665.

doi pubmed - Uemura H, Ishiguro H, Nagashima Y, Sasaki T, Nakaigawa N, Hasumi H, Kato S, et al. Antiproliferative activity of angiotensin II receptor blocker through cross-talk between stromal and epithelial prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(11):1699-1709.

doi pubmed - Ye G, Qin Y, Lu X, Xu X, Xu S, Wu C, Wang X, et al. The association of renin-angiotensin system genes with the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;459(1):18-23.

doi pubmed - Puddefoot JR, Udeozo UK, Barker S, Vinson GP. The role of angiotensin II in the regulation of breast cancer cell adhesion and invasion. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13(3):895-903.

doi pubmed - Zhang Q, Lu S, Li T, Yu L, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Qian X, et al. ACE2 inhibits breast cancer angiogenesis via suppressing the VEGFa/VEGFR2/ERK pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):173.

doi pubmed - Feng Y, Wan H, Liu J, Zhang R, Ma Q, Han B, Xiang Y, et al. The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in tumor growth and tumor-associated angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(4):941-948.

doi pubmed - Zhou L, Zhang R, Yao W, Wang J, Qian A, Qiao M, Zhang Y, et al. Decreased expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is associated with tumor progression. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;217(2):123-131.

doi pubmed - Zong H, Yin B, Zhou H, Cai D, Ma B, Xiang Y. Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 promotes growth of gallbladder cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(7):5171-5177.

doi pubmed - Yang J, Li H, Hu S, Zhou Y. ACE2 correlated with immune infiltration serves as a prognostic biomarker in endometrial carcinoma and renal papillary cell carcinoma: implication for COVID-19. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(8):6518-6535.

doi pubmed - Bernardi S, Zennaro C, Palmisano S, Velkoska E, Sabato N, Toffoli B, Giacomel G, et al. Characterization and significance of ACE2 and Mas receptor in human colon adenocarcinoma. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2012;13(1):202-209.

doi pubmed - Hanski C. Is mucinous carcinoma of the colorectum a distinct genetic entity? Br J Cancer. 1995;72(6):1350-1356.

doi pubmed - Tozawa E, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, Nishikura K, Mukai G, Suda T, Kanoh T, et al. Mucin expression, p53 overexpression, and peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration of advanced colorectal carcinoma with mucus component: is mucinous carcinoma a distinct histological entity? Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203(8):567-574.

doi pubmed - Hyngstrom JR, Hu CY, Xing Y, You YN, Feig BW, Skibber JM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, et al. Clinicopathology and outcomes for mucinous and signet ring colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(9):2814-2821.

doi pubmed - Pei N, Wan R, Chen X, Li A, Zhang Y, Li J, Du H, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) decreases cell growth and angiogenesis of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15(1):37-47.

doi pubmed - Krishnan B, Torti FM, Gallagher PE, Tallant EA. Angiotensin-(1-7) reduces proliferation and angiogenesis of human prostate cancer xenografts with a decrease in angiogenic factors and an increase in sFlt-1. Prostate. 2013;73(1):60-70.

doi pubmed - Soto-Pantoja DR, Menon J, Gallagher PE, Tallant EA. Angiotensin-(1-7) inhibits tumor angiogenesis in human lung cancer xenografts with a reduction in vascular endothelial growth factor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(6):1676-1683.

doi pubmed - Xu J, Fan J, Wu F, Huang Q, Guo M, Lv Z, Han J, et al. The ACE2/Angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas receptor axis: pleiotropic roles in cancer. Front Physiol. 2017;8:276.

doi pubmed - Yu C, Tang W, Wang Y, Shen Q, Wang B, Cai C, Meng X, et al. Downregulation of ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas axis promotes breast cancer metastasis by enhancing store-operated calcium entry. Cancer Lett. 2016;376(2):268-277.

doi pubmed - Chen Y, Hou W, Zhong M, Wu B. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of colon cancer tissue revealed the reason for the worse prognosis of right-sided colon cancer and mucinous colon cancer at the protein level. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(5):3554-3572.

doi pubmed - Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, Fu J, Sahu A, Hu X, Li Z, et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med. 2018;24(10):1550-1558.

doi pubmed - Bao R, Hernandez K, Huang L, Luke JJ. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression by clinical, HLA, immune, and microbial correlates across 34 human cancers and matched normal tissues: implications for SARS-CoV-2 COVID-19. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2).

doi pubmed - Niu M, Yi M, Wu Y, Lyu L, He Q, Yang R, Zeng L, et al. Synergistic efficacy of simultaneous anti-TGF-beta/VEGF bispecific antibody and PD-1 blockade in cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16(1):94.

doi pubmed - Philip M, Schietinger A. CD8(+) T cell differentiation and dysfunction in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(4):209-223.

doi pubmed - Wu X, Gu Z, Chen Y, Chen B, Chen W, Weng L, Liu X. Application of PD-1 blockade in cancer immunotherapy. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2019;17:661-674.

doi pubmed - Reina-Campos M, Scharping NE, Goldrath AW. CD8(+) T cell metabolism in infection and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(11):718-738.

doi pubmed - Shalapour S, Lin XJ, Bastian IN, Brain J, Burt AD, Aksenov AA, Vrbanac AF, et al. Inflammation-induced IgA+ cells dismantle anti-liver cancer immunity. Nature. 2017;551(7680):340-345.

doi pubmed - Ducoin K, Oger R, Bilonda Mutala L, Deleine C, Jouand N, Desfrancois J, Podevin J, et al. Targeting NKG2A to boost anti-tumor CD8 T-cell responses in human colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2022;11(1):2046931.

doi pubmed - Pakbin B, Dibazar SP, Allahyari S, Shariatifar H, Bruck WM, Farasat A. ACE2-inhibitory effects of bromelain and ficin in colon cancer cells. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(2).

doi pubmed - Mostafa AM, Hamdy NM, Abdel-Rahman SZ, El-Mesallamy HO. Effect of vildagliptin and pravastatin combination on cholesterol efflux in adipocytes. IUBMB Life. 2016;68(7):535-543.

doi pubmed - Atta H, Alzahaby N, Hamdy NM, Emam SH, Sonousi A, Ziko L. New trends in synthetic drugs and natural products targeting 20S proteasomes in cancers. Bioorg Chem. 2023;133:106427.

doi pubmed - Chiang YF, Huang KC, Chen HY, Hamdy NM, Huang TC, Chang HY, Shieh TM, et al. Hinokitiol inhibits breast cancer cells in vitro stemness-progression and self-renewal with apoptosis and autophagy modulation via the CD44/Nanog/SOX2/Oct4 pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7).

doi pubmed - Uversky VN, Elrashdy F, Aljadawi A, Ali SM, Khan RH, Redwan EM. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection reaches the human nervous system: How? J Neurosci Res. 2021;99(3):750-777.

doi pubmed - Esposito G, Pesce M, Seguella L, Sanseverino W, Lu J, Sarnelli G. Can the enteric nervous system be an alternative entrance door in SARS-CoV2 neuroinvasion? Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:93-94.

doi pubmed - Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61(5):759-767.

doi pubmed - Kasi A, Handa S, Bhatti S, Umar S, Bansal A, Sun W. Molecular pathogenesis and classification of colorectal carcinoma. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2020;16(5):97-106.

doi pubmed - Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, Kinde I, Wang Y, Agrawal N, Bartlett BR, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra224.

doi pubmed - Kuhn N, Klinger B, Uhlitz F, Sieber A, Rivera M, Klotz-Noack K, Fichtner I, et al. Mutation-specific effects of NRAS oncogenes in colorectal cancer cells. Adv Biol Regul. 2021;79:100778.

doi pubmed - Prior IA, Hood FE, Hartley JL. The frequency of ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2020;80(14):2969-2974.

doi pubmed - Feng J, Hu Z, Xia X, Liu X, Lian Z, Wang H, Wang L, et al. Feedback activation of EGFR/wild-type RAS signaling axis limits KRAS(G12D) inhibitor efficacy in KRAS(G12D)-mutated colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2023;42(20):1620-1633.

doi pubmed - Rubinson DA, Tanaka N, Fece de la Cruz F, Kapner KS, Rosenthal MH, Norden BL, Barnes H, et al. Sotorasib is a pan-RASG12C inhibitor capable of driving clinical response in NRASG12C cancers. Cancer Discov. 2024;14(5):727-736.

doi pubmed - Han H, Luo RH, Long XY, Wang LQ, Zhu Q, Tang XY, Zhu R, et al. Transcriptional regulation of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 by SP1. Elife. 2024;13.

doi pubmed - Palakkott AR, Alneyadi A, Muhammad K, Eid AH, Amiri KMA, Akli Ayoub M, Iratni R. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein activates the epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated signaling. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(4).

- Deben C, Le Compte M, Siozopoulou V, Lambrechts H, Hermans C, Lau HW, Huizing M, et al. Expression of SARS-CoV-2-related surface proteins in non-small-cell lung cancer patients and the influence of standard of care therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(17).

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, including commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.