| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://wjon.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 2, April 2025, pages 227-234

Solitary Synchronous Biliary Metastasis in Colorectal Adenocarcinoma

Kyla Wrighta, Michael A. Mederosb, Irene R. Riahic, Bita V. Nainic, Jena Depetrisd, Mark D. Girgisa, e

aDepartment of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

bDepartment of Surgery, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10065, USA

cDepartment of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

dDepartment of Radiological Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, 90095, USA

eCorresponding Author: Mark D. Girgis, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

Manuscript submitted December 6, 2024, accepted February 8, 2025, published online March 18, 2025

Short title: Biliary Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon2008

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Malignant biliary obstruction can, in rare cases, arise from metastases to the biliary tree from distant primary tumors. This phenomenon often poses a diagnostic challenge, as bile duct metastases may clinically and radiologically mimic primary biliary tumors, such as cholangiocarcinoma. We present a unique case of solitary, synchronous intraductal biliary metastasis in a patient with colorectal adenocarcinoma that led to biliary obstruction. The patient initially presented with a new diagnosis of colon cancer at the hepatic flexure and was found, on cross-sectional imaging, to have biliary obstruction due to an intraductal mass. Initially, the nature of the intraductal lesion was uncertain; however, it was ultimately confirmed through histopathological examination to be metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. This case underscores the difficulty of distinguishing metastatic biliary obstruction from primary biliary tumors and highlights the importance of considering metastatic disease in atypical presentations of biliary masses. We discuss several key radiologic and histopathological features that may help differentiate intraductal colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases from primary biliary tumors.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer; Colorectal adenocarcinoma; Biliary metastasis; Cholangiocarcinoma; Malignant biliary obstruction

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Malignant biliary obstruction most commonly arises from primary cancers of the pancreas, bile ducts, gallbladder, liver, or ampulla of Vater. Rarely, it can be caused by metastases to the biliary system from distant primary tumors, including renal, lung, gastric, breast, and colorectal cancers [1]. Biliary metastasis is exceedingly uncommon, and most existing literature on the subject is limited to single case reports or small case series [2-4]. Furthermore, diagnosis can be challenging, as malignant biliary obstruction due to extrahepatic biliary metastases may clinically and radiologically resemble primary biliary tumors like cholangiocarcinoma.

We present a rare case of an isolated synchronous intrabiliary metastasis in a patient with colorectal adenocarcinoma. While liver metastases emerge in approximately one-third of patients with colorectal cancer, intrabiliary metastases are exceptionally rare, most arising from the direct extension of intrahepatic metastases into the bile ducts [5]. Here, we report a case of an isolated, intrabiliary metastasis originating from colorectal adenocarcinoma that resulted in biliary obstruction. Though a case of metachronous intrabiliary metastases from colorectal cancer has been described [6], to our knowledge, a solitary, synchronous biliary metastasis from colorectal cancer has not previously been reported.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

The patient was a male in his 50s with a maternal familial history of pancreatic cancer who initially presented with symptomatic anemia secondary to a lower gastrointestinal bleed. Colonoscopy revealed a nearly obstructive circumferential lesion at the hepatic flexure, with biopsy demonstrating moderately differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma (microsatellite stable (MSS), intact expression of mismatch repair (MMR) proteins; human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative, KRAS G12D mutation, BRAF wild-type).

Computed tomography (CT) re-demonstrated the colonic mass at the hepatic flexure, with trace pericolonic fat stranding and surrounding lymphadenopathy. However, he was also noted to have right-sided intrahepatic biliary ductal dilation with an obstructing mass in the right intrahepatic bile duct near the biliary hilum (Fig. 1). Initially, it was unclear whether this hilar mass represented metastatic disease or a second synchronous primary malignancy.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) Coronal post-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrating mass-like wall thickening of the cecum spanning approximately 8 cm in length compatible with biopsy-proven adenocarcinoma. (b) Axial post-contrast-enhanced portal venous phase CT showing an enhancing mass within the right bile duct (arrow) measuring 1.1 × 1.3 cm with associated right-sided intrahepatic biliary dilation. |

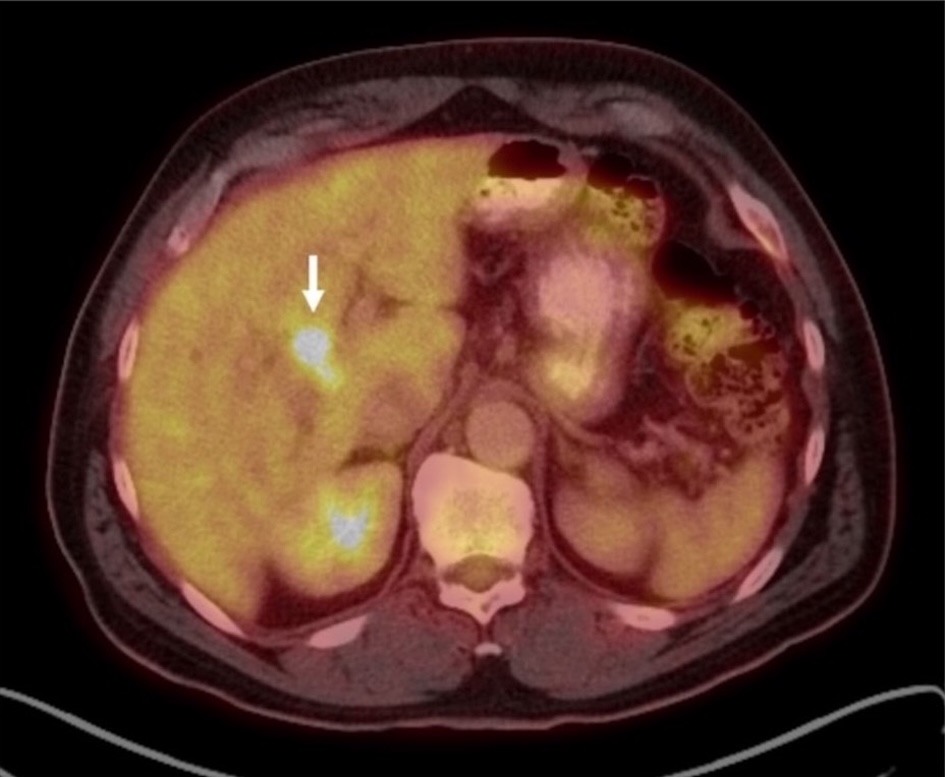

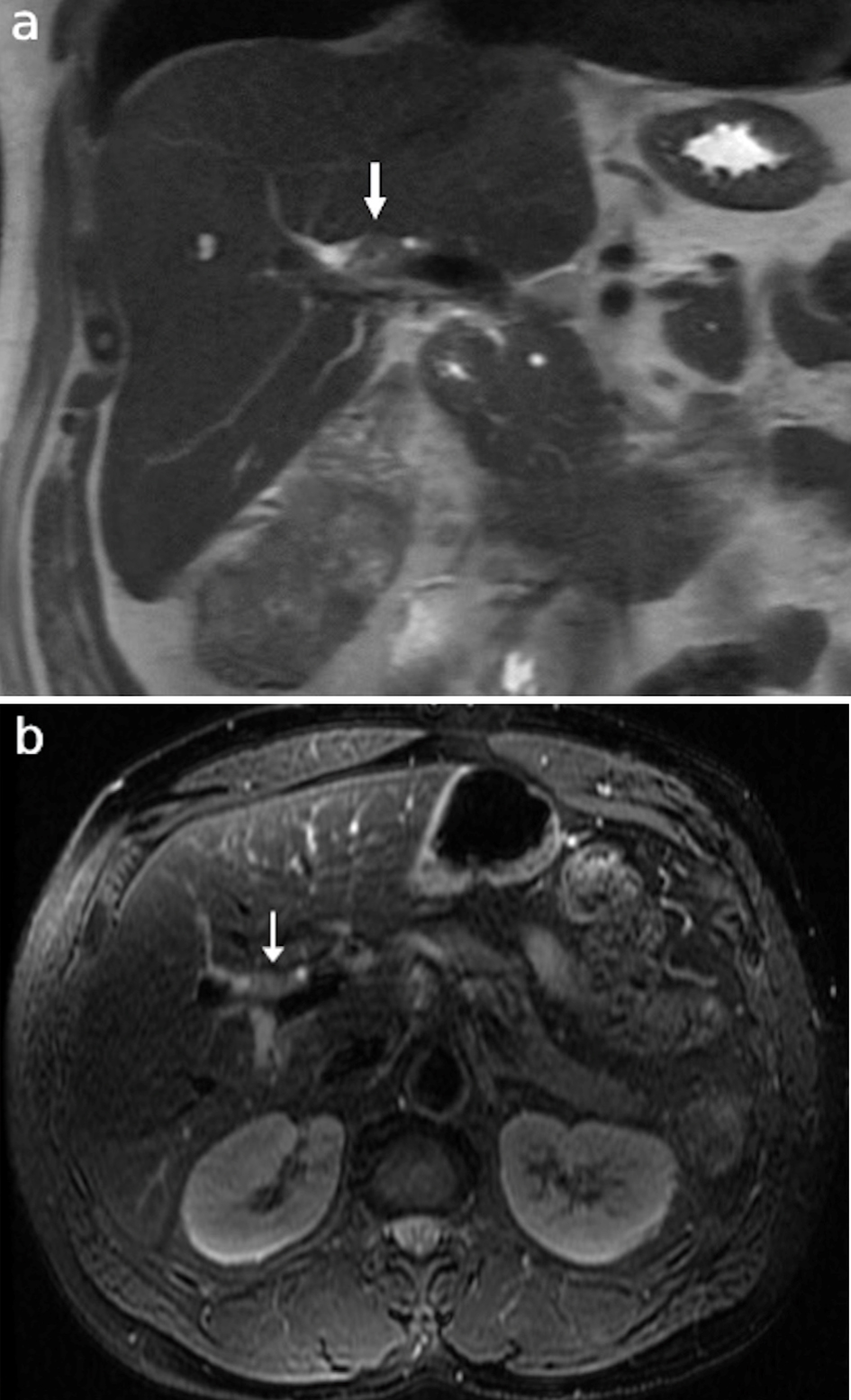

The patient underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), which identified benign-appearing porta hepatis and para-aortic lymph nodes. Biopsies of these nodes, performed via fine needle aspiration (FNA), returned negative for malignancy. However, positron emission tomography (PET)/CT demonstrated suspicious fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid ileocolic and pericaval lymph nodes, along with intense, focal FDG uptake in a 2.1 cm lesion in the right lobe of the liver (Fig. 2). A liver biopsy was attempted but unsuccessful due to the inability to definitively visualize the lesion on ultrasound at the time of the procedure. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was subsequently performed, which demonstrated the lesion in the proximal right intrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Fused axial 18F-FDG PET/CT showing intense, focal FDG uptake (SUV max 9.6) in a 2.1 cm lesion near the porta hepatis (arrow). 18F-FDG: 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose; CT: computed tomography; PET: positron emission tomography; SUV: standardized uptake value. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Representative (a) coronal T2 HASTE sequence and (b) axial T2 fat saturated sequence MRCP images showing an intermediate T2 signal mass (arrows) within the proximal right intrahepatic bile duct corresponding to the focus of radiotracer uptake on prior PET. HASTE: half-Fourier acquired single-shot turbo spin-echo; MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; PET: positron emission tomography. |

At this time, the patient’s carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was mildly elevated at 7.8 µg/L, while his carbohydrate antigen 19-19 (CA19-9) was within the normal range (21 U/mL). He underwent four cycles of neoadjuvant XELOX chemotherapy (oxaliplatin and capecitabine), with minimal decrease in the size and increased radiotracer uptake of the ascending colon mass and adjacent ileocolic and pericaval nodes. There was no significant change in focal radiotracer uptake within the right hepatic lobe on repeat PET/CT and little change in his CEA level.

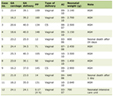

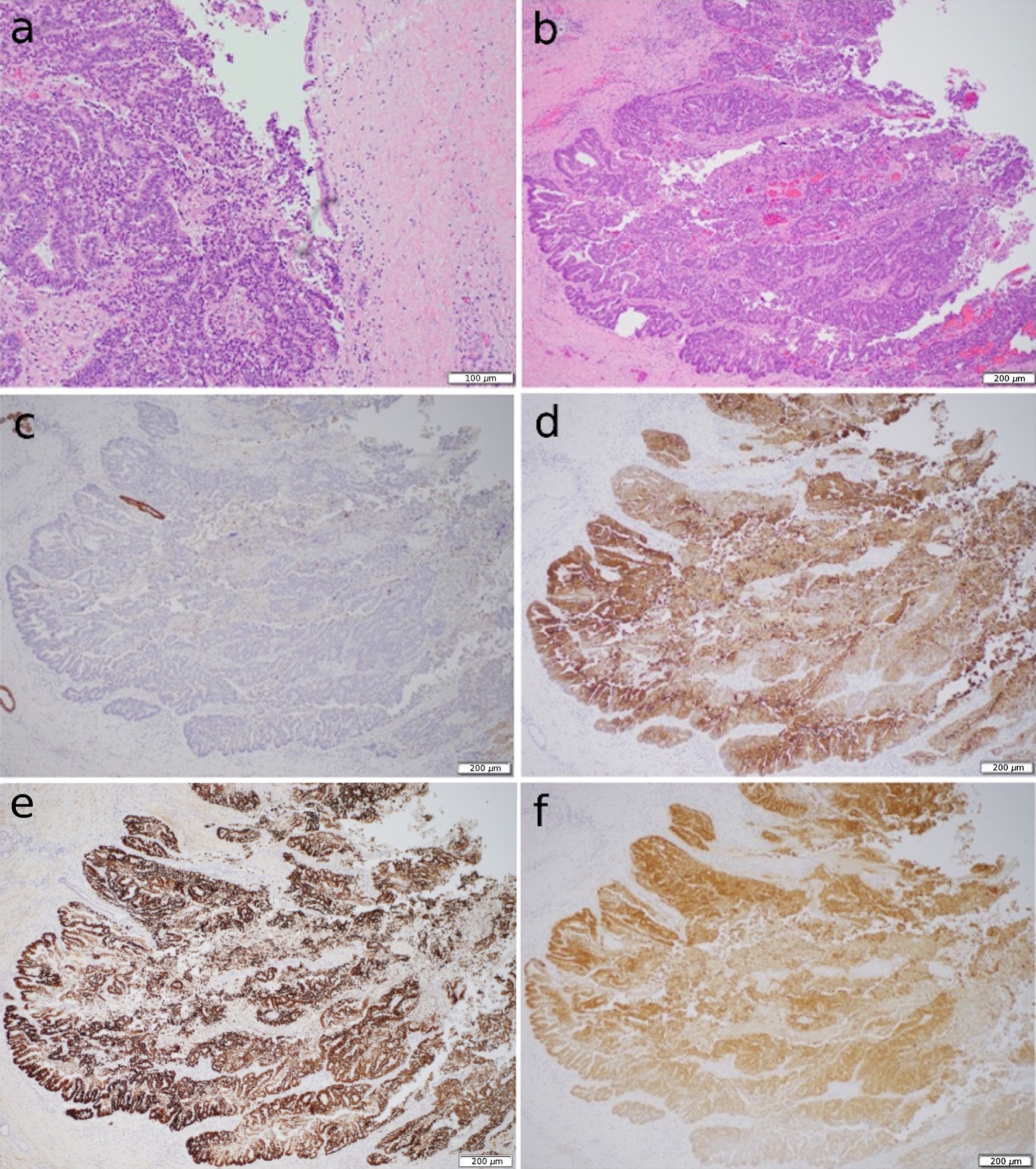

Unfortunately, the patient subsequently developed a large bowel obstruction secondary to colo-colonic intussusception from his colon cancer. The patient was taken urgently to the operating room for a laparoscopic procedure, which was converted to an open right hemicolectomy. On pathologic examination, the tumor measured 9.5 × 6.8 × 2.5 cm, invaded through the muscularis propria, and 29 lymph nodes were negative for adenocarcinoma (American Joint Committee on Cancer, eighth edition (AJCC 8), pT3N0 staging). An intraoperative ultrasound was performed and noted a hypoechoic 0.5 × 0.7 cm lesion in segment III of the liver and a 1 × 1 cm lesion within the right hepatic duct. The segment III lesion was biopsied and negative for malignancy. Postoperatively, the patient underwent a second ERCP with cholangioscopy (Fig. 4) and biopsy of the right hepatic duct lesion, which was noted endoscopically to have tumor vessels seen alongside the wall of the duct. Pathology demonstrated well-to-moderately differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma with the same morphology as the colorectal adenocarcinoma. It also showed immunophenotype characteristics of colorectal adenocarcinoma (cytokeratin 7 (CK7) negative, cytokeratin 20 (CK20) positive, SATB2 positive). Similarly, it showed the same molecular signature as the colorectal adenocarcinoma (KRAS G12D point mutation, MSS, two APC mutations, mutations in PIK3CA, PPPR21A, ZFHX3).

Click for large image | Figure 4. ERCP cholangiogram showing irregular filling defect within the right bile duct corresponding to the location of the known mass (arrow). ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. |

An interval MRI was performed following his index operation, which again demonstrated an infiltrative, central T2 intermediate, T1 and hepatobiliary hypointense, diffusion-restricting hepatobiliary mass in the proximal hepatic hilum. Compared to the patient’s initial MRI approximately 8 months prior, the mass demonstrated slight expansile growth, measuring 3.0 × 2.0 cm in diameter compared to 2.1 cm in maximum diameter previously, with mildly increased associated right greater than left intrahepatic biliary dilation.

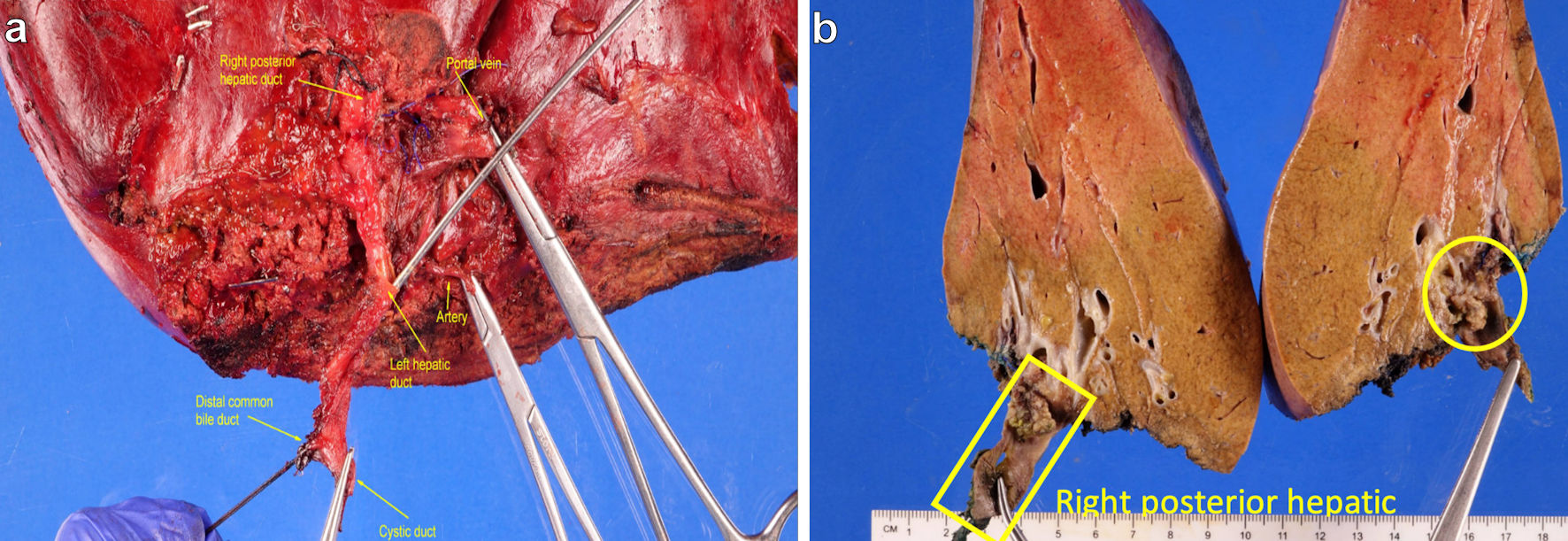

Seven months after his initial colon resection, the patient underwent an open right liver resection, portal lymphadenectomy and extrahepatic bile duct resection with Roux-en-Y left hepaticojejunostomy. He did not receive additional systemic therapy between the two operations. Intraoperatively, a hilar intraductal mass was identified extending to the right bile duct. A frozen margin from the left proximal bile duct, which was sent intraoperatively, was negative for malignancy.

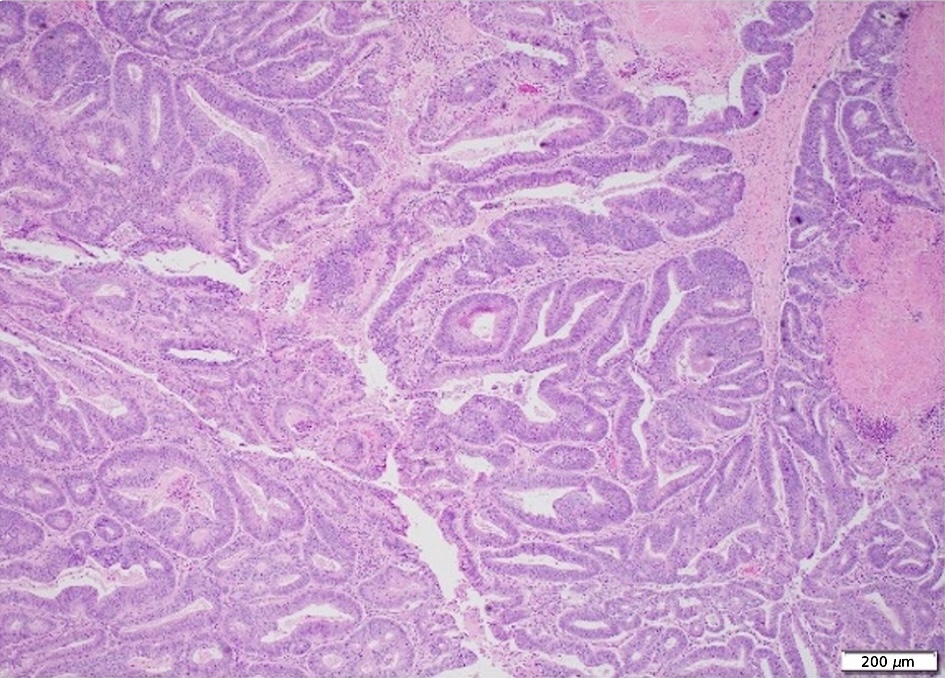

A gross pathologic examination of the specimen was remarkable for a tan-yellow, exophytic mass measuring 2.1 × 1.7 × 1.1 cm within the right hepatic bile duct (Fig. 5). The mass was confined to the bile duct without invasion into the hepatic parenchyma. Further microscopic examination confirmed moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with clear margins. The prior colon and bile duct specimens were reviewed in conjunction with our pathologists. They were noted to have similar pathologic features, consistent with metastatic colon cancer to the bile duct (Table 1, Figs. 6, 7). Three periportal and omental lymph nodes were negative for metastatic disease.

Click for large image | Figure 5. (a) Hepatic hilar region. (b) Yellow square marks right posterior hepatic bile duct and yellow circle marks tan-yellow friable and exophytic mass involving the duct. |

Click to view | Table 1. Immunohistochemical and Molecular Profiles of Resected Cecal and Bile Duct Lesions |

Click for large image | Figure 6. Section of the cecal mass with invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma |

Click for large image | Figure 7. (a, b) Sections of the right hepatic bile duct with exophytic mass. The mass has similar morphology to the cecal mass. (c) CK7 immunohistochemistry with no expression. (d, e, f) CK20, CDX2 and SATB2 immunohistochemistry with positive diffused expression, respectively. CK7: cytokeratin 7; CK20: cytokeratin 20. |

The patient is now 1-year post-index operation and 4 months post-liver resection. He is receiving adjuvant chemotherapy with irinotecan and Zirabev (bevacizumab-bvzr) with no evidence of disease.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Metastases to the bile ducts are exceedingly rare, and existing literature on the topic largely consists of case reports and small series [2-4]. Most reports describe a microscopic or macroscopic invasion of the biliary tree in patients with hepatic metastases; intrabiliary lesions without an associated hepatic mass are even more uncommon [7, 8]. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, including vascular invasion with spread via a peribiliary capillary plexus [9] and direct spread via the bile stream [10]. Determining the most likely mechanism, in this case, is challenging, as the surgical specimen showed no signs of lymphatic or vascular invasion and no concurrent hepatic masses suggesting biliary invasion. However, the patient’s neoadjuvant therapy may have obscured these findings in the resected specimens. In addition, a majority (> 90%) of described cases are metachronous in presentation, with a median interval of 60 months between the time of diagnosis of the primary tumor and of intrabiliary metastasis [11]. In contrast, our case of colon cancer with biliary metastasis is unique due to the solitary and synchronous nature of the metastasis.

Neoplastic biliary obstruction is frequently presumed to be from a primary intraductal biliary neoplasm until proven otherwise [12]. Due to their rarity, biliary metastases may be mistaken for a primary neoplasm of the bile duct, such as cholangiocarcinoma. However, several radiologic and histopathologic differences have been identified to help differentiate cholangiocarcinoma and intrabiliary metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma and other extrabiliary malignancies. Of note, tumor markers, including CEA and CA19-9, are unlikely to be beneficial in differentiating colorectal adenocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma, as they can be elevated in both conditions [13].

Several radiologic features may help differentiate biliary metastases from primary intrabiliary neoplasms preoperatively. A retrospective review by Lee et al found that neoplastic biliary obstruction from a lesion contiguous with the adjacent liver parenchyma supports a diagnosis of extrabiliary metastases (e.g., liver metastases with extension into the bile duct lumen), whereas purely intraductal masses are more likely to represent cholangiocarcinoma [12]. Interestingly, this was not true of our patient’s biliary mass, which appeared purely intraductal on preoperative imaging without evidence of originating from the adjacent liver parenchyma. The mild to moderate right biliary dilation may be attributed to partial obstruction of the right hepatic duct lumen. Pathologic analysis of the resected specimen confirmed that the mass was purely intraductal.

Lee et al also found that intraductal metastases are more likely to have an expansile appearance on imaging, whereas cholangiocarcinoma is more likely to exhibit a papillary appearance [12]. This distinction is owed to differences in the tumor’s histologic growth pattern: intraductal metastases are more likely to exhibit intraluminal tumor growth, resembling tumor thrombi and resulting in an expansile appearance on cross-sectional imaging. In contrast, intraepithelial extension, in which the tumor advances along the intact basement membrane, replacing the normal bile duct epithelium, is more likely to occur in primary biliary cancers and results in a papillary growth pattern on imaging [14, 15]. The space-occupying nature of the mass described in this report is consistent with these findings. This became more evident as time progressed and the biliary mass increased in size, expanding the bile duct lumen due to its growth, and was most consistent with an expansile-type growth pattern due to intraductal metastasis. Lastly, the authors found that calcifications were more frequent in patients with intrabiliary metastases from colorectal cancer compared to cholangiocarcinoma, likely because fine and punctate calcifications can occur in mucinous adenocarcinoma, a common histological subtype of colorectal cancer. However, this finding was not statistically significant. They did not find tumor size, multiplicity, signal intensity or enhancement patterns to differ significantly between the two pathologies [12].

The most reliable method to distinguish intrabiliary neoplasms from intraductal, extrabiliary metastases is pathological analysis. In patients with resectable cholangiocarcinoma undergoing up-front surgery, preoperative tissue diagnosis is generally not recommended due to the potential risk of tumor seeding [16]. However, for patients with more advanced diseases, a preoperative biopsy may be performed to guide neoadjuvant chemotherapy, aiming to reduce the tumor burden to allow for adequate resection [17]. Certainly, when differentiating biliary metastases from primary biliary neoplasms, histologic diagnosis may have important therapeutic indications. In our case, a preoperative biopsy was attempted via ERCP with EUS; however, a tissue sample was not obtained due to the inability to visualize the lesion on ultrasound reliably. Various techniques can be employed to biopsy biliary lesions, including ERCP with EUS and FNA, ERCP with endoscopic brushings, and percutaneous transhepatic intraductal biopsy. Each method has its limitations, with a wide range of reported sensitivities and specificities for each [18]. Interestingly, a review by Davidson et al found that preoperative CT had the highest reported diagnostic accuracy [18]. Further, most studies on biopsy methods focus on differentiating malignant from benign disease. We would expect the accuracy of these methods in distinguishing carcinomas of different origins to be even lower.

Once an adequate tissue sample is obtained, several histologic features can be used to confirm the diagnosis. As previously mentioned, differences in the microscopic appearance and growth pattern may distinguish the two conditions: intraductal metastases are more likely to exhibit intraluminal, expansile tumor growth, whereas cholangiocarcinoma more frequently demonstrates intraepithelial extension with papillary tumor growth. However, there are notable exceptions to these growth patterns. For example, unlike other extrabiliary metastases, intraductal metastasis from colorectal cancer may exhibit intraepithelial extension, making the distinction from primary biliary malignancies more difficult. Further, multiple morphological subtypes of cholangiocarcinoma demonstrate different growth patterns. Papillary growth is often seen with the intraductal growing subtype but is not seen in the periductal infiltrating subtype [19]. Thus, immunohistochemistry more reliably confirms the diagnosis. Specifically, CK7 and CK20 are key markers in distinguishing intrabiliary metastases from cholangiocarcinoma [11, 12]. Colorectal epithelium is typically CK20 positive and CK7 negative, while biliary epithelium shows the opposite pattern [12]. A retrospective review found that, in practice, 70-95% of colorectal cancers and 20-40% of pancreaticobiliary adenocarcinomas are CK20 positive, whereas 90-100% of pancreaticobiliary and 5-25% of colorectal adenocarcinomas are CK7 positive [20]. Thus, a majority of colorectal cancer metastases are CK7 negative and CK20 positive [21, 22], but 9-16% may be CK20 negative [11]. A recent systematic review by Latorre Fragua et al confirmed this pattern in cases of intrabiliary metastases from colorectal cancer, with 19 of 23 cases being CK20 positive and 19 of 22 being CK7 negative [11]. CDX2 and SATB2 are more frequently positive in colorectal adenocarcinoma as well [23]. This staining pattern (CK20, CDX2, and SATB2 positive, CK7 negative) was true in our case as well, confirming the diagnosis.

The only definitive cure for malignant biliary obstruction, whether due to intrabiliary metastasis or cholangiocarcinoma, is surgical resection. Anatomical resection is generally recommended, particularly in cases where the preoperative diagnosis (metastasis versus primary biliary malignancy) is undetermined [11]. Because of cholangiocarcinoma’s characteristic longitudinal growth along the bile duct walls, concerns exist that nonanatomic wedge resection might leave surgical margins too narrow to fully remove the affected ducts [24]. For cholangiocarcinoma, a complete surgical resection with histologically negative margins is essential and is the preferred management approach in medically fit patients with resectable disease [25]. In colorectal cancer, the combination of medical therapy and surgical resection of liver metastases has been shown to improve cure rates and overall survival [26]. However, given its rarity, little is known regarding the impact of resecting intrabiliary metastases on patient survival in colorectal cancer.

Conclusions

This case highlights the difficulties in differentiating metastatic biliary obstruction from primary biliary tumors. Several radiological features may help to distinguish the two entities preoperatively, including the presence versus absence of extension into the hepatic parenchyma and papillary versus expansile appearance. However, diagnostic confirmation ultimately requires histopathological examination, with CK20 and CK7 being the two most important immunohistochemical markers. The presence of biliary obstruction from metastases is important to consider in atypical presentations of biliary masses, particularly in patients with a coexisting malignancy, as it may have therapeutic and prognostic implications.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Informed Consent

Verbal, informed consent was obtained from the study participant, and all clinical data was appropriately deidentified.

Author Contributions

KW participated in drafting and revising the manuscript. MM, IR, BN and JD contributed to the content and revised the manuscript. MG conceptualized the article and oversaw all aspects of manuscript drafting and finalization.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

CK7: cytokeratin 7; CK20: cytokeratin 20; CT: computed tomography; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS: endoscopic ultrasound; FNA: fine needle aspiration; MMR: mismatch repair; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MSS: microsattelite stable

| References | ▴Top |

- Okamoto T. Malignant biliary obstruction due to metastatic non-hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28(10):985-1008.

doi pubmed - Kawakatsu S, Kaneoka Y, Maeda A, Takayama Y, Fukami Y, Onoe S. Intrapancreatic bile duct metastasis from colon cancer after resection of liver metastasis with intrabiliary growth: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:254.

doi pubmed - Otsuka N, Nakagawa Y, Uchinami H, Yamamoto Y, Arita J. Gastric cancer simultaneously complicated with extrahepatic bile duct metastasis and portal vein tumor thrombus: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2023;9(1):182.

doi pubmed - Tang J, Zhao GX, Deng SS, Xu M. Rare common bile duct metastasis of breast cancer: A case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13(2):147-156.

doi pubmed - Morris VK, Kennedy EB, Baxter NN, Benson AB, 3rd, Cercek A, Cho M, Ciombor KK, et al. Treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(3):678-700.

doi pubmed - Kawashima K, Watanabe N, Tawada S, Adachi T, Yamada M, Kitoh Y, Takeuchi T, et al. Intrahepatic biliary metastasis of colonic adenocarcinoma: a case report with immunohistochemical analysis. World J Oncol. 2017;8(3):86-91.

doi pubmed - Uehara K, Hasegawa H, Ogiso S, Sakamoto E, Igami T, Ohira S, Mori T. Intrabiliary polypoid growth of liver metastasis from colonic adenocarcinoma with minimal invasion of the liver parenchyma. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(1):72-75.

doi pubmed - Wenzel DJ, Gaede JT, Wenzel LR. Case report. Intrabiliary colonic metastasis mimicking primary biliary neoplasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(4):1029-1032.

doi pubmed - Sahani DV, Kalva SP. Imaging the liver. Oncologist. 2004;9(4):385-397.

doi pubmed - Nanashima A, Tobinaga S, Araki M, Kunizaki M, Abe K, Hayashi H, Harada K, et al. Intraductal papillary growth of liver metastasis originating from colon carcinoma in the bile duct: report of a case. Surg Today. 2011;41(2):276-280.

doi pubmed - Latorre Fragua RA, Manuel Vazquez A, Rodrigues Figueira Y, Ramiro Perez C, Lopez Marcano AJ, de la Plaza Llamas R, Ramia Angel JM. Intrabiliary metastases in colorectal cancer: a systematic review. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019;26(7):270-280.

doi pubmed - Lee YJ, Kim SH, Lee JY, Kim MA, Lee JM, Han JK, Choi BI. Differential CT features of intraductal biliary metastasis and double primary intraductal polypoid cholangiocarcinoma in patients with a history of extrabiliary malignancy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(4):1061-1069.

doi pubmed - Qin XL, Wang ZR, Shi JS, Lu M, Wang L, He QR. Utility of serum CA19-9 in diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma: in comparison with CEA. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(3):427-432.

doi pubmed - Yoon KH, Ha HK, Kim CG, Roh BS, Yun KJ, Chae KM, Lim JH, et al. Malignant papillary neoplasms of the intrahepatic bile ducts: CT and histopathologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(4):1135-1139.

doi pubmed - Lim JH, Park CK. Pathology of cholangiocarcinoma. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29(5):540-547.

doi pubmed - Khan SA, Davidson BR, Goldin R, Pereira SP, Rosenberg WM, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thillainayagam AV, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: consensus document. Gut. 2002;51:vi1-vi9.

doi pubmed - Ghio M, Vijay A. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Evolving role of neoadjuvant and targeted therapy. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2023;27(2):123-130.

doi pubmed - Davidson BR, Gurusamy K. Is preoperative histological diagnosis necessary for cholangiocarcinoma? HPB (Oxford). 2008;10(2):94-97.

doi pubmed - Mederos MA, Girgis MD. Anatomic and morphologic classifications of cholangiocarcinoma. In: Tabibian JH. Diagnosis and management of cholangiocarcinoma: a multidisciplinary approach. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 11-26.

- Rullier A, Le Bail B, Fawaz R, Blanc JF, Saric J, Bioulac-Sage P. Cytokeratin 7 and 20 expression in cholangiocarcinomas varies along the biliary tract but still differs from that in colorectal carcinoma metastasis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(6):870-876.

doi pubmed - Lau SK, Prakash S, Geller SA, Alsabeh R. Comparative immunohistochemical profile of hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(12):1175-1181.

doi pubmed - Tot T. Adenocarcinomas metastatic to the liver: the value of cytokeratins 20 and 7 in the search for unknown primary tumors. Cancer. 1999;85(1):171-177.

doi pubmed - Berg KB, Schaeffer DF. SATB2 as an immunohistochemical marker for colorectal adenocarcinoma: a concise review of benefits and pitfalls. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141(10):1428-1433.

doi pubmed - Peungjesada S, Aloia TA, Kaur H, Marcal L, Choi H, Vauthey JN, Loyer EM. Intrabiliary growth of colorectal liver metastasis: spectrum of imaging findings and implications for surgical management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201(4):W582-589.

doi pubmed - Esnaola NF, Meyer JE, Karachristos A, Maranki JL, Camp ER, Denlinger CS. Evaluation and management of intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer. 2016;122(9):1349-1369.

doi pubmed - Gallagher DJ, Kemeny N. Metastatic colorectal cancer: from improved survival to potential cure. Oncology. 2010;78(3-4):237-248.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.