| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://wjon.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 000, Number 000, October 2025, pages 000-000

Immediate Breast Reconstruction Using an Expanded Latissimus Dorsal Musculocutaneous Flap Without Body Position Change

Miwako Miyasakaa, e , Megumi Kiyoia, Aya Shimaa, Yoshimitsu Hiraia, Kazuaki Takabeb, c, d, Yoshiharu Nishimuraa

aDepartment of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Wakayama Medical University, Wakayama, Japan

bBreast Surgery, Department of Surgical Oncology, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, NY 14263, USA

cDepartment of Immunology, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, NY, USA

dDepartment of Surgery, University at Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, The State University of New York, Buffalo, NY 14263, USA

eCorresponding Author: Miwako Miyasaka, Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Wakayama Medical University, Wakayama 641-8509, Japan

Manuscript submitted August 7, 2025, accepted September 16, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Breast Reconstruction Using an eLDMC Flap

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon2651

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Breast reconstruction using expanded latissimus dorsal musculocutaneous flap (eLDMC flap) is known for excellent outcome; however, intraoperative change in body position to assess cosmesis prolongs operative time. Here, we present the results and the strengths of immediate breast reconstruction with an eLDMC flap without body position change that we have developed.

Methods: Two hundred twenty-three patients who underwent total mastectomy followed by immediate breast reconstruction using eLDMC flaps between November 2010 and December 2018 at Wakayama Medical University Hospital were analyzed for operative times, complications, conformity, local recurrence, and distant metastasis. Forty-eight patients without reconstruction during the same period were also analyzed.

Results: The median time of follow-up after operation was 57 months (0 - 121 months). The mean operation time was 183.6 min (115 - 291 min), which was approximately 4 - 6 h shorter than the reported technique with body position changes. Complications occurred in 130 patients (58.3%) and there was seroma in 103 patients (79.2%). There was local recurrence in 12 cases (5.4%), and distant metastasis occurred in six cases (2.7%). The recurrence rate was equivalent to that of previous reports. A total of 208 patients (93.3%) were evaluated to be excellent or good.

Conclusion: Immediate breast reconstruction with an eLDMC flap without body position change is a safe, quick, and sufficient surgical procedure. Our surgical method achieves shorter operation times without compromising cosmetic appearance or increasing the complications and recurrence rate.

Keywords: Extended latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap; Immediate breast reconstruction; Breast cancer; No change position

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Breast cancer is the most common type of malignant tumor in women in Japan [1]. Following breast cancer surgery, good cosmesis as well as curative results is desired. Breast reconstruction operations are increasingly performed at the time of mastectomy, resulting in better physical and psychological satisfaction and improved breast cancer-specific survival [2-6]. In a Japanese study, the immediate reconstruction rate for 1,616 patients that underwent mastectomy at 389 hospitals in 2010 was 11.2%, a demonstration of the growth in immediate reconstruction in recent years [7]. Since July 2013, Natrelle (Allergan Inc., Santa Barbara, CA) has been covered in universal medical insurance in Japan as a breast implant for reconstruction after breast cancer surgery. Breast reconstruction using an implant aims to restore the shape and volume of the original breast, but the result is firmer and moves less naturally than reconstruction using native tissue. There may therefore be difficulty in attaining a natural shape and symmetry when one breast, rather than both, was reconstructed using implants. Unlike natural breasts, the implant breasts do not ptose with age and may appear higher than the contralateral (natural) breast, particularly as the patient gets older. If patients lose or gain weight, this will affect the natural breast but not the reconstructed breast, causing difference in shape and size. Patients may eventually need more surgery for the reconstructed breast, or to the other breast, to achieve a better match and symmetry [8].

An alternative to using implants in reconstruction after mastectomy is reconstruction by abdominal skin valve (deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flap (DIEP flap)) with a large amount of fatty tissue. The technique is technically difficult; however, because it includes anastomosis under a microscope, the operation time is long, and complications may occur, such as flap necrosis due to vascular occlusion. As a further development, an expanded latissimus dorsal musculocutaneous flap (eLDMC flap) with a large amount of fat attached to the lumbar region has been used at our institution since 2010. The eLDMC flap allows for more tissue to be obtained than the traditional latissimus dorsal musculocutaneous flap and is easier to harvest than the DIEP flap. Reconstruction of breasts thought to be sufficiently close to native, pre-mastectomy size without the need for vascular anastomosis or without implants has been possible by this method.

The current most commonly employed immediate breast reconstruction is implant-based. However, many institutions, particularly the ones in rural areas or low socioeconomic countries, may not have the luxury of access to implants or plastic surgeons. At those institutions where many of our readers are located [9], autologous tissue reconstruction using eLDMC flap is a viable option for breast surgeons. Breast cancer surgery performed solely in the lateral decubitus position without body position change has been considered to be technically difficult. Owing to limited available operating room time however, to shorten the operation time, we have performed breast cancer surgery and reconstruction without repositioning. The complications and appearance of reconstructive surgery using an eLDMC flap have not been widely reported [10], although it has been given a grade C1 recommendation in cancer treatment guidelines [11]. There have been no reported means of performing breast cancer surgery and breast reconstruction without body position change. Here, we discuss the surgical results and the conformity of no body position change breast surgery and immediate breast reconstruction with an eLDMC flap at our institution.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This study was approved by the Wakayama Medical University Ethical Review Committee (Approval No. 3133). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study is a retrospective cohort study. Indications for eLDMC reconstruction include the absence of lymph node metastasis on imaging, no evidence of nipple areola complex (NAC) invasion on imaging, and the absence of bilateral lesions. eLDMC reconstruction was performed upon patient’s request and when the eligibility criteria were met. Since this is a cohort study, no randomization was applied in the decision of performing this procedure.

Included were 223 patients with primary breast cancer that underwent unilateral mastectomy: skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) or nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) followed by immediate breast reconstruction using an eLDMC flap at our institution between November 2010 and December 31 2018, and 48 patients from the same period with primary breast cancer that underwent unilateral NSM mastectomy without reconstruction. Sentinel node biopsy (SNB) was performed under local anesthesia in most cases until December 2015 to confirm negative metastasis or only micrometastasis. From January 2016, SNB was performed at the same time as breast surgery, but only in cases where preoperative axillary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed low possibility of metastasis. Operative times, blood loss, complications, appearance, local recurrence, and distant metastasis were examined and statistically evaluated for each case. The drain was removed when the daily drainage volume fell below 20 mL or 2 weeks has passed after the operation. Seroma was defined as the condition requiring needle aspiration drainage after drain removal. Wound detachment is defined as the failure of a sutured surgical wound to achieve primary healing, resulting in partial or complete separation of the wound edges. Nipple necrosis was defined as a condition where all or part of the nipple tissue turns dark red or black, necessitating surgical intervention. Surgical site infection was defined as requiring antibiotic administration or wound debridement.

A means of evaluation of postoperative cosmetic outcome was proposed in 2004 by the Japanese Breast Cancer Society Sawai Group (Sawai Group) [12]. In this scoring method, evaluation is made using eight items related to the form of the breasts: breast size, breast shape, scar, breast firmness, nipple and areola size/shape, nipple and areola color/tone, nipple position, and position of the maximum descent point of the breast [13]. To evaluate the appearance after breast reconstruction, four levels (excellent, good, fair, and poor) are used based on symmetry.

Statistical analyses

Comparison of the patient characteristics and operation date between cohorts was performed using a paired t-test. Risk factor of seroma was performed using a Chi-square test. The time to the occurrence of the end point events or the date of last contact was calculated from the date of surgery. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The JMP Pro (Version 14, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Surgical technique of immediate breast reconstruction with an eLDMC flap without body position change

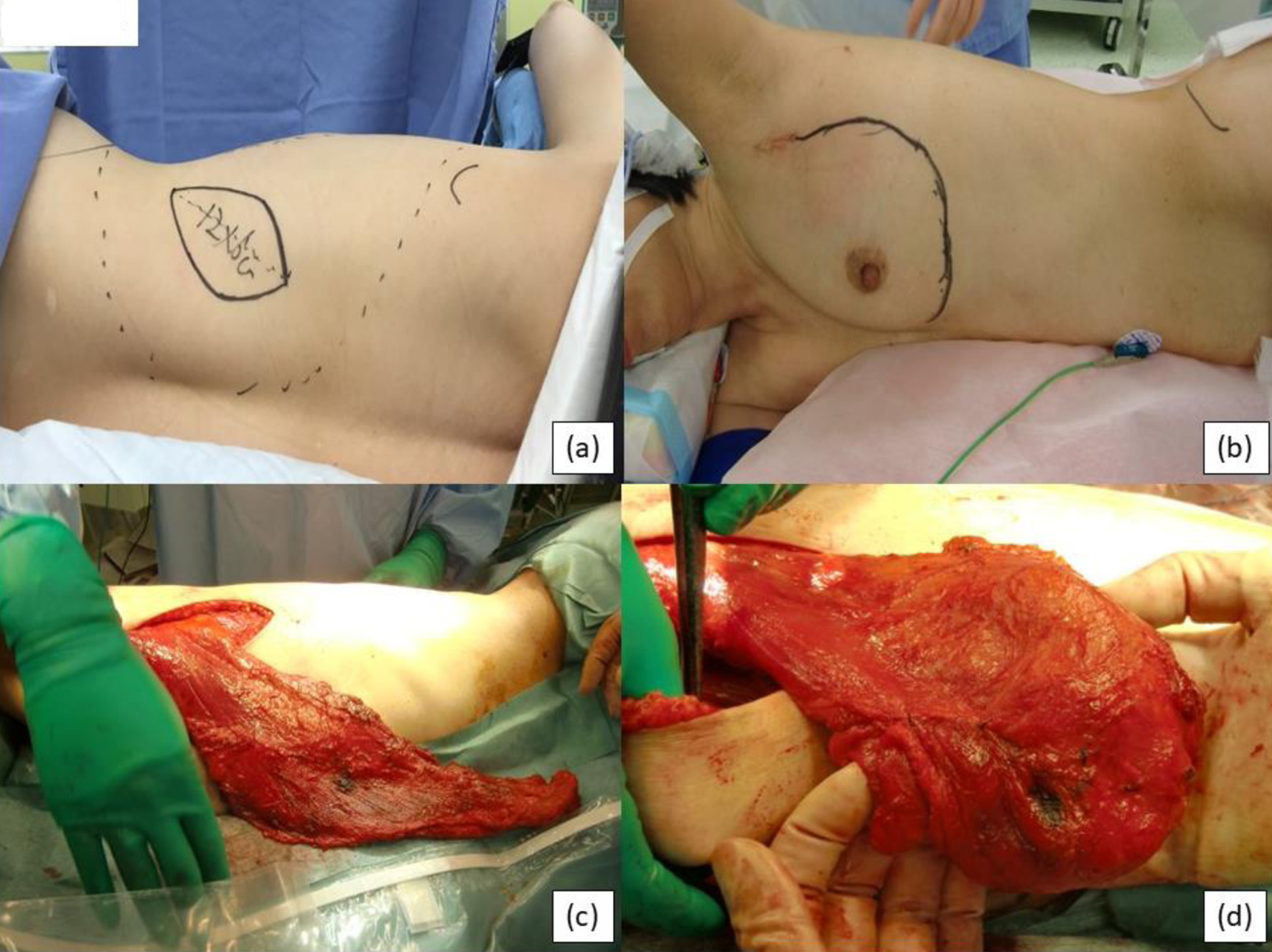

Under general anesthesia in the operating room, the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position and the surgeon first stands at the patient’s back (Fig. 1a, b). For breast cancer surgery, a 10 - 12 cm vertical incision is made on the anterior axillary line and mastectomy (SSM or NSM) is performed. First, the serratus anterior muscle is identified, followed by dissection to expose the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle. The posterior surface of the mastectomy area is then dissected, including the fascia of the pectoralis major muscle. At this time, subcutaneous fat should be left intact as much as possible. In detail, a thin flap of subcutaneous adipose tissue is left close to the tumor, but a thick flap of subcutaneous adipose tissue is preserved at a distance of more than 2 cm from the tumor. To ensure complete removal of the tissue under the NAC, the nipple was everted to facilitate dissection, and the major ducts were removed from the lumen. To avoid nipple necrosis, the tissue under the NAC was carefully treated to preserve the vessels feeding the nipple. The NAC was resected if there was any evidence of neoplastic involvement on the basis of frozen section analysis [14]. Creating a flap in the medial region of the breast is particularly difficult, so care is required when removing the residual mammary gland and tumor tissue. Elevation of the eLDMC flap is continued after mastectomy is complete. At this time, the surgeon stands on the ventral side of the patient to harvest the flap. A skin incision is made along the periphery of the spindle-shaped skin island on the lumbar region to reach the shallow fascia layer of the vastus lateralis muscle (Fig. 1a). At the shallow fascia layer, the vastus lateralis muscle is resected with the subcutaneous fat. In the lumbar region, the flap can be harvested with more fat from beyond the vastus lateralis to the foot. Fat that is too distal can easily become necrotic however, so we recommend limiting the fat attachment to a distance of about 2 - 3 cm from the vastus lateralis muscle area. The elevated flap is transferred to the breast through a subcutaneous tunnel in the axilla (Fig. 1c). The fat at the distal end of the elevated flap is folded posteriorly in two and is used to create breast elevation (Fig. 1d). The flap is then sutured to the pectoralis major muscle in three places (medial superior pole of the breast, and medial and lateral sides of the inframammary fold (IMF) line). Additional sutures aid in preventing flap migration as well as protecting the pedicle from excess tension. Drains are placed in the back and under the skin of the anterior chest, and the back wound is closed with sutures. Images of the surgery are shown in Figure 1.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Intraoperative images. (a) Preoperative back skin incision design. (b) Preoperative breast design. (c) Flap moved to the prothorax. (d) Flap folded in two and formed into the breast shape. |

| Results | ▴Top |

Patient details are shown in Table 1. Patients’ mean age was 49.7 years old (24 - 80), median body mass index (BMI) was 21.8 (17.2 - 37.7), stage was 0 in 53 patients, I in 114 patients, IIA in 38 patients, IIB in 16 patients, IIIA in two patients, and median follow-up was 58 months (0 - 124 months). The reconstruction group was younger. Although it is generally considered that reconstruction is more common in early-stage breast cancer, there was no difference in stage in our study group.

Click to view | Table 1. Clinical and Pathological Characteristics of Breast Cancer Patients With and Without Immediate Reconstruction |

Comparisons of operation time, blood loss, and surgery method of breast between our cohort and the report by Sakai et al with body position change [15] are shown in Table 2. The median operating time was 183.6 min (115 - 291 min), the mean blood loss was 73.2 mL (5 - 322 mL), and the most common techniques for breast cancer were NSM in 107 cases and NSM + SNB in 85 cases. According to the report by Sakai et al, the average operating time was 418 min, the average blood loss was 618 mL, and the most common techniques for breast cancer were SSM + SNB in 108 cases. Both blood loss and operation time were significantly reduced.

Click to view | Table 2. Comparisons of Operation Time, Blood Loss, and Surgery Method of Breast Between Our Study and Report by Sakai et al [15] |

Comparisons of complications between our study and another report with body position change are shown in Table 3 [15]. Complications occurred in 130 patients (58.3%): there was seroma in 103 patients (46.2%), epidermal necrosis of the nipple in eight patients (3.6%), wound dehiscence in nine patients (4.0%), and wound infection in five patients (2.2%). According to a report by Sakai et al, complications occurred in 120 patients (69.0%): there was seroma in 71 patients (41.0%), epidermal necrosis of the nipple in four patients (2.3%), wound dehiscence in 43 patients (24.6%), and wound infection in one patient (0.5%).

Click to view | Table 3. Complication With Immediate Reconstruction |

The results of the examination of risk factors for seroma, the most common complication, are shown in Table 4. ROC analysis was used to determine the optimal cutoff values. The results yielded an age cutoff of 50 years, an operation time cutoff of 173 min, and a BMI cutoff of 21.5. Multivariate analysis was then conducted using these cutoffs.

Click to view | Table 4. Risk Factor of Seroma |

There was a significant difference in risk factors for seroma with BMI > 21.5 (P = 0.0007) and age > 50 years (P = 0.0202). Surgical time of ≥ 173 min (P = 0.0505) is not considered a risk factor (Table 4).

Local recurrence occurred in 12 cases (5.4%), and metastasis occurred in six cases (2.7%, four bone cases, two liver cases, and one lung case; there was one instance of dual metastasis) [16].

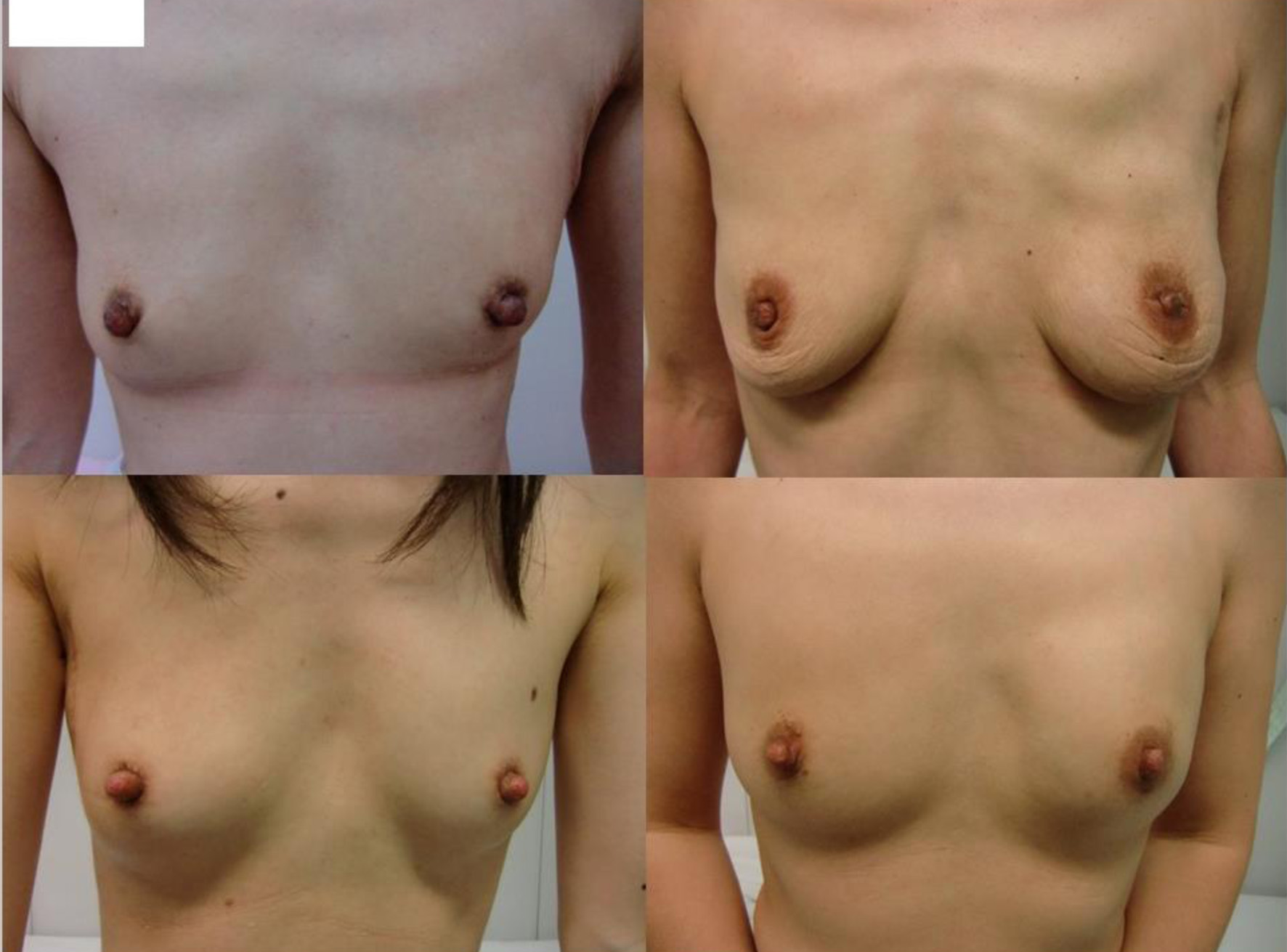

Regarding appearance, 153 patients were considered to have excellent appearance (68.6%), 55 good (24.7%), seven fair (3.1%), and one poor (0.4%). Evaluation of the acceptability is shown in Table 5. According to a report by Du et al, 37 patients were considered to have excellent appearance (58.7%), 19 good (30.2%), five fair (7.9%), and two poor (3.2%) [17]. According to a report by Adel et al, 85 patients were considered to have excellent appearance (60.8%), 42 good (30.0%), 10 fair (7.1%), and three poor (2.1%) [18]. The evaluation of cosmetic appearance was similar to that reported in other studies.

Click to view | Table 5. Aesthetic Grading Results of Breast Reconstruction |

Pre- and postoperative breasts are shown in Figures 2-4.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Postoperative images of the representative four patients with small-sized breasts. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Postoperative images of the representative four patients with standard-sized breasts. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Postoperative images of the representative four patients with large-sized breasts. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The eLDMC flap is close to the breast and thus can be easily used in breast reconstruction. The eLDMC flap allows for more tissue to be obtained than the traditional latissimus dorsal musculocutaneous flap and is easier to harvest than the DIEP flap. Postoperative recovery is faster than when abdominal flaps are used [19]. Exercise such as swimming and golfing is possible after just 2 months, so this operation has been commonly used in breast reconstruction for a long time. There are also drawbacks, however, such as insufficient tissue volume for reconstruction after mastectomy, and the need for intraoperative repositioning. Reconstruction with an eLDMC flap was first reported by Hokin in 1983 [20]. eLDMC flaps are thought to compensate for the lack of tissue volume in people with lower BMI. Meanwhile, the balance of the left and right breasts cannot be confirmed without body position change, so there were strong concerns that the patients may be dissatisfied with the results. The measurements used in the present study, evaluated by surgeons, were subjective but 208 of the cases (93.3%) were considered to have either “good” or “excellent” appearance, which was the majority, and the merits of the reconstruction could be sufficiently shown.

There are various reports on the time required for surgery using abdominal flaps (6 - 9), while reconstruction using an eLDMC flap with position change (supine to lateral to supine) has been reported to take 4 - 5 h [18, 20]. Our method can be completed in approximately 3 h, in other words, by using this technique, the pressure on the surgical schedule may be reduced. The time can be further reduced if the surgeon and surgical team are skilled.

The local recurrence rate in this cohort was 12 cases (5.4%) (median observation period: 57 months), while the local recurrence observed by Sakurai et al was reported as 8.2% of patients (median observation period: 78 months) [14, 21, 22]. In a report of primary reconstruction using expanders and implants by McCarthy et al, the local recurrence rate was 6.8% in the reconstruction group and 8.1% in the non-reconstruction group, with a mean observation period of 67 months; there was no significant difference between the two groups [23]. Langstein et al reported a local recurrence rate of 39/1,694 (2.3%) over a 10-year observation period in patients who underwent primary breast reconstruction using predominantly transverse rectus abdominus muscle flaps [24]. In our institution, the local recurrence rate was 4/48 (8.3%) in NSM without reconstruction during the same period (median observation period: 55 months, 0 - 121 months). The rate of local recurrence did not increase with reconstruction, although it may be necessary for the surgical team to gain proficiency in supine-position breast surgery and to detach a thin skin flap near the tumor.

Clough et al reported the following complications of eLDMC flap: seroma (72%), hematoma (5%), bleeding (4.1%), wound separation (3.3%), infection (1.7%), partial flap necrosis (1.7%), and fat necrosis (1.7%) [25]. Sakai et al reported the following complications of eLDMC flap: seroma (41%), wound separation (24.6%), nipple necrosis (2.3%), and infection (0.5%) [15]. There was no significant difference in the incidence of complications. Chang et al also reported that the risk of these complications is increased if the patient is ≥ 65 years of age, if they have a D cup (difference between the bust size and the band size of 17.5 cm) or larger, or if they have a BMI of ≥ 30 [26]. In the present study, patients with BMI > 21.5 kg/m2 and age > 50 years had significantly higher likelihood of developing seroma. Development of seroma should be noted in the reconstruction of patients with this condition.

Ninety percent of Japanese breast cancer patients had a BMI below 30 kg/m2 [27], which is a risk factor for complications. In a comparison of the body sizes of Japanese people living in Japan, Japanese people living in Hawaii, and Caucasian people living in Hawaii, the mean BMI was reported as 23.2, 23.1, and 25.0 kg/m2, respectively, and the mean breast sizes were 55.69, 56.41, and 87.77 cm2, respectively [28]. Further versatility of this flap was shown in a series of 277 patients, which demonstrated acceptable flap and donor site complications with the eLDMC flap, even in obese and overweight patients [29]. Although the use of an eLDMC flap is thought to be unsuitable for patients with large breasts due to insufficient tissue volume, it can still be considered as an option for patients with a BMI of about 22 kg/m2, which is common in Japan, and in patients whose breasts are not very large, as in most of our cases (Table 1, median BMI 21.8 kg/m2).

Limitations of this study include that only a subjective evaluation was performed for the cosmetic appearance and that the observation period was insufficient for detection of local recurrence. Future studies should include breast characteristics (breast size, degree of breast ptosis), excision volume, and mammary gland density, which are factors that particularly affect the cosmetic appearance, and the use of quantitative evaluation methods, such as 3D measurement of breast volume and long-term observation. Unfortunately, the weight of the resected breast was not measured nor recorded, which would have supported the patient selection for eLDMC reconstruction. Post hoc power analysis indicated a required sample size of approximately 130 per group, which was larger than the power of the current study. We consider that more cases need to be accumulated. Functional impairment following an extensive harvest of the latissimus dorsi muscle at the donor site is a recognized risk [10], and efforts have been made to minimize this morbidity including muscle-sparing techniques [30], often combined with lipofilling [31]. Therefore, medium- or long-term evaluation of functional sequelae at the latissimus dorsi donor site after eLDMC flap is of interest [32]. Unfortunately, however, we do not have access to such information, which would enable a more detailed assessment of reconstruction outcomes. Despite these shortcomings, we do believe that our approach will be a viable choice at institutions where there is no access to plastic surgeons, implants, nor advanced plastic surgical options.

Conclusions

Immediate breast reconstruction with an eLDMC flap without body position change is a safe, quick, and comfortable surgical procedure. Our surgical method achieves shorter operation times without reducing cosmetic appearance or increasing the complications or increasing the recurrence rate.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge proofreading and editing by Benjamin Phillis at the Clinical Study Support Center, Wakayama Medical University.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Miwako Miyasaka, Megumi Kiyoi, and Aya Shima. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Miwako Miyasaka and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

BMI: body mass index; DIEP flap: deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flap; eLDMC flaps: expanded latissimus dorsal musculocutaneous flaps; IMF: inframammary fold; NAC: nipple areola complex; NSM: nipple-sparing mastectomy; SNB: sentinel node biopsy; SSM: skin-sparing mastectomy

| References | ▴Top |

- The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Vital Statistics of Japan. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/vs01.html. Accessed August 5, 2025.

- Roth RS, Lowery JC, Davis J, Wilkins EG. Psychological factors predict patient satisfaction with postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(7):2008-2015.

doi pubmed - Ueda S, Tamaki Y, Yano K, Okishiro N, Yanagisawa T, Imasato M, Shimazu K, et al. Cosmetic outcome and patient satisfaction after skin-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer with immediate reconstruction of the breast. Surgery. 2008;143(3):414-425.

doi pubmed - Bezuhly M, Temple C, Sigurdson LJ, Davis RB, Flowerdew G, Cook EF, Jr. Immediate postmastectomy reconstruction is associated with improved breast cancer-specific survival: evidence and new challenges from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Cancer. 2009;115(20):4648-4654.

doi pubmed - Alderman AK, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. Use of breast reconstruction after mastectomy following the Women's Health and Cancer Rights Act. JAMA. 2006;295(4):387-388.

doi pubmed - Katsuragi R, Ozturk CN, Chida K, Mann GK, Roy AM, Hakamada K, Takabe K, et al. Updates on breast reconstruction: surgical techniques, challenges, and future directions. World J Oncol. 2024;15(6):853-870.

doi pubmed - Oda A, Kuwabara H, Fushimi K. Disparities associated with breast reconstruction in Japan. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(6):1392-1399.

doi pubmed - Howard-McNatt MM. Patients opting for breast reconstruction following mastectomy: an analysis of uptake rates and benefit. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2013;5:9-15.

doi pubmed - Takabe K, Day V, Benesch MGK. The dimensions of reports from around the world that address diversity in oncology. World J Oncol. 2022;13(5):241-243.

doi pubmed - Chirappapha P, Thaweepworadej P, Chitmetha K, Rattadilok C, Rakchob T, Wattanakul T, Lertsithichai P, et al. Comparisons of complications between extended latissimus dorsi flap and latissimus dorsi flap in total breast reconstruction: A prospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;56:197-202.

doi pubmed - Clinical Practice Guidelines of Japanese Society for Cancer. http://www.jsco-cpg.jp/plastic-surgery7/guideline/#II. [Japanese].

- Sawai K, Nakajima H, Ichihara S, Yano K, Watanabe O, Kitamura K, Akashi S, et al. Research of cosmetic evaluation and extent of resection for breast conserving surgery. 12th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Breast Cancer Society. 2004;12:. [Abstract] #107-8.

- Nohara Y, Hanamura N, Zaha H, Kimura H, Kashikura Y, Nakamura T, Noro A, et al. Cosmetic evaluation methods adapted to Asian patients after breast-conserving surgery and examination of the necessarily elements for cosmetic evaluation. J Breast Cancer. 2015;18(1):80-86.

doi pubmed - Sakurai T, Zhang N, Suzuma T, Umemura T, Yoshimura G, Sakurai T, Yang Q. Long-term follow-up of nipple-sparing mastectomy without radiotherapy: a single center study at a Japanese institution. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):481.

doi pubmed - Sakai Y, Sakai S. Breast reconstruction with an extended latissumus dorsi myocutaneous flap. Report of 174 cases. The Journal of the Japan Surgical Association. 1998;59(6):1471-1476. [Japanese]

- Yano K, Hosokawa K, Masuoka T, Matsuda K, Takada A, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, et al. Options for immediate breast reconstruction following skin-sparing mastectomy. Breast Cancer. 2007;14(4):406-413.

doi pubmed - Du Z, Zhou Y, Chen J, Long Q, Lu Q. Retrospective observational study of breast reconstruction with extended latissimus dorsi flap following skin-sparing mastectomy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(31):e10936.

doi pubmed - Denewer A, Setit A, Hussein O, Farouk O. Skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction by a new modification of extended latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap. World J Surg. 2008;32(12):2586-2592.

doi pubmed - Hokin JA. Mastectomy reconstruction without a prosthetic implant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72(6):810-818.

doi pubmed - Ishida T, Kusaba T, Sakata K, Tokumine M, Shioya K, Teshigawa O. Changing trend of breast cancer surgery. Results and assessment of breast-conserving surgery and immediate breast reconstruction. IRYO. 1997;51(11):512-517. [Japanese]

- Wu ZY, Kim HJ, Lee JW, Chung IY, Kim JS, Lee SB, Son BH, et al. Breast cancer recurrence in the nipple-areola complex after nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction for invasive breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(11):1030-1037.

doi pubmed - Romics L, Jr., Chew BK, Weiler-Mithoff E, Doughty JC, Brown IM, Stallard S, Wilson CR, et al. Ten-year follow-up of skin-sparing mastectomy followed by immediate breast reconstruction. Br J Surg. 2012;99(6):799-806.

doi pubmed - McCarthy CM, Pusic AL, Sclafani L, Buchanan C, Fey JV, Disa JJ, Mehrara BJ, et al. Breast cancer recurrence following prosthetic, postmastectomy reconstruction: incidence, detection, and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(2):381-388.

doi pubmed - Langstein HN, Cheng MH, Singletary SE, Robb GL, Hoy E, Smith TL, Kroll SS. Breast cancer recurrence after immediate reconstruction: patterns and significance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(2):712-720; discussion 721-712.

doi pubmed - Clough KB, Louis-Sylvestre C, Fitoussi A, Couturaud B, Nos C. Donor site sequelae after autologous breast reconstruction with an extended latissimus dorsi flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(6):1904-1911.

doi pubmed - Chang DW, Youssef A, Cha S, Reece GP. Autologous breast reconstruction with the extended latissimus dorsi flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(3):751-759; discussion 760-751.

doi pubmed - Japanese Breast Cancer Society. National Breast Cancer Patient Registry Survey Report. http://memberpage.jbcs.gr.jp/uploads/ckfinder/files/nenjitouroku/2018kakutei.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2025.

- Maskarinec G, Nagata C, Shimizu H, Kashiki Y. Comparison of mammographic densities and their determinants in women from Japan and Hawaii. Int J Cancer. 2002;102(1):29-33.

doi pubmed - Yezhelyev M, Duggal CS, Carlson GW, Losken A. Complications of latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction in overweight and obese patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70(5):557-562.

doi pubmed - Piat JM, Tomazzoni G, Giovinazzo V, Dubost V, Maiato AP, Ho Quoc C. Lipofilled mini dorsi flap: an efficient less invasive concept for immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;85(4):369-375.

doi pubmed - Fauconnier MB, Burnier P, Jankowski C, Loustalot C, Coutant C, Vincent L. Comparison of postoperative complications following conventional latissimus dorsi flap versus muscle-sparing latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75(10):3653-3663.

doi pubmed - Steffenssen MCW, Kristiansen AH, Damsgaard TE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional shoulder impairment after latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;82(1):116-127.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.